Three weeks ago, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released its annual stat fest, Education at a Glance (see last week’s blog for more on this year’s higher education and financing data). The most interesting thing about this edition is that the OECD chose to release some new data from the recent Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) relating to literacy and numeracy levels that were included in the PIAAC 2013 release (see also here), but not in the December 2024 release.

(If you need a refresher: PIAAC is kind of like the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) but for adults and is carried out once a decade so countries can see for themselves how skilled their workforces are in terms of literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving).

The specific details of interest that were missing in the earlier data release were on skill level by level of education (or more specifically, highest level of education achieved). OECD for some reason cuts the data into three – below upper secondary, upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary, and tertiary. Canada has a lot of post-secondary non-tertiary programming (a good chunk of community colleges are described this way) but for a variety of reasons lumps all college diplomas in with university degrees in with university degrees as “tertiary”, which makes analysis and comparison a bit difficult. But we can only work with the data the OECD gives us, so…

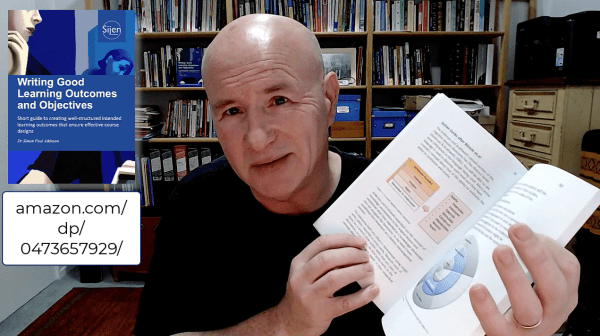

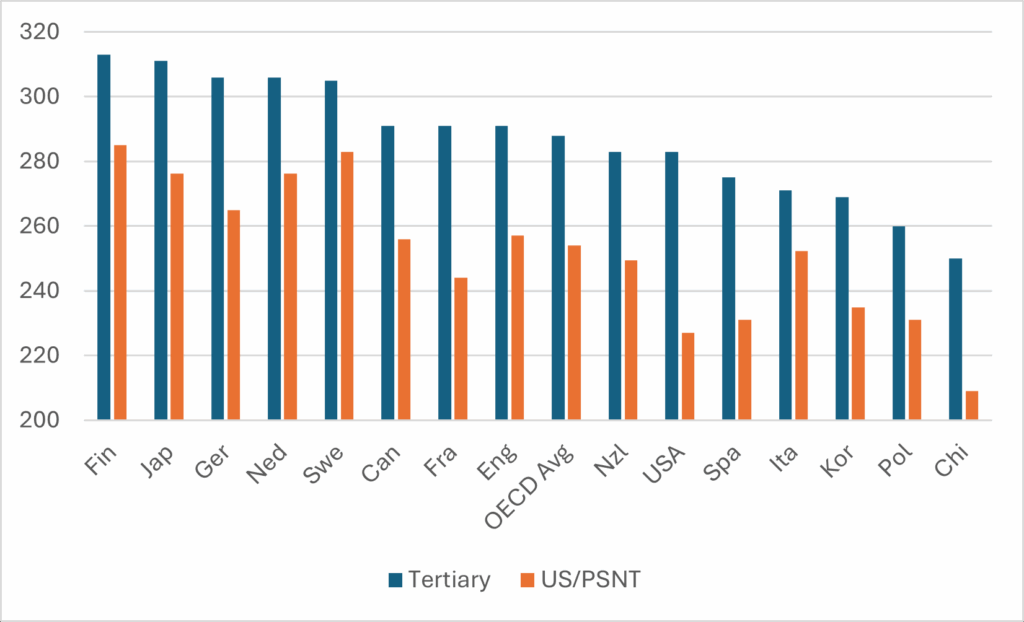

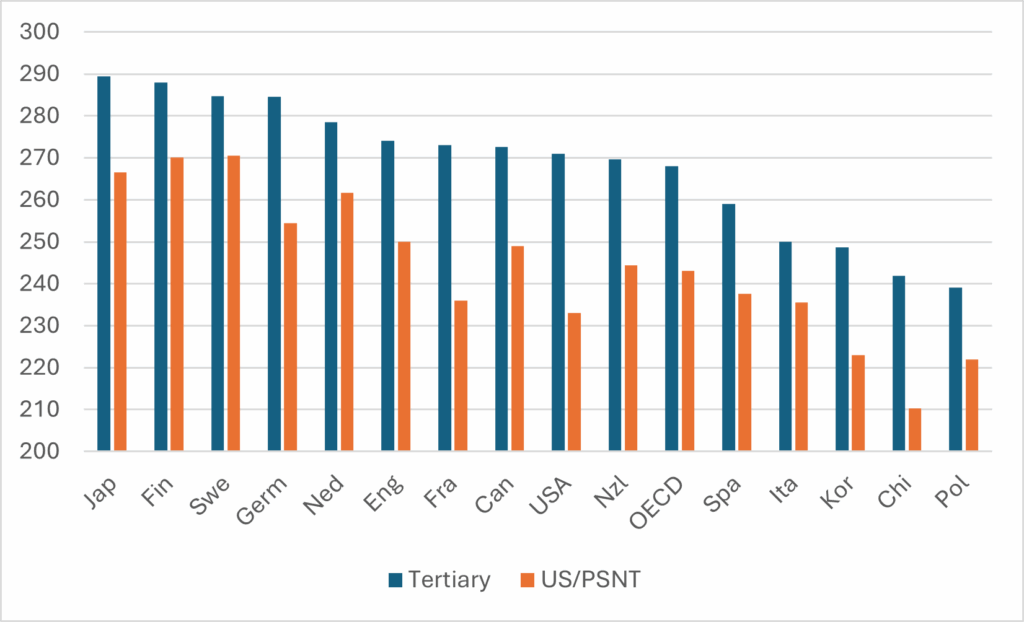

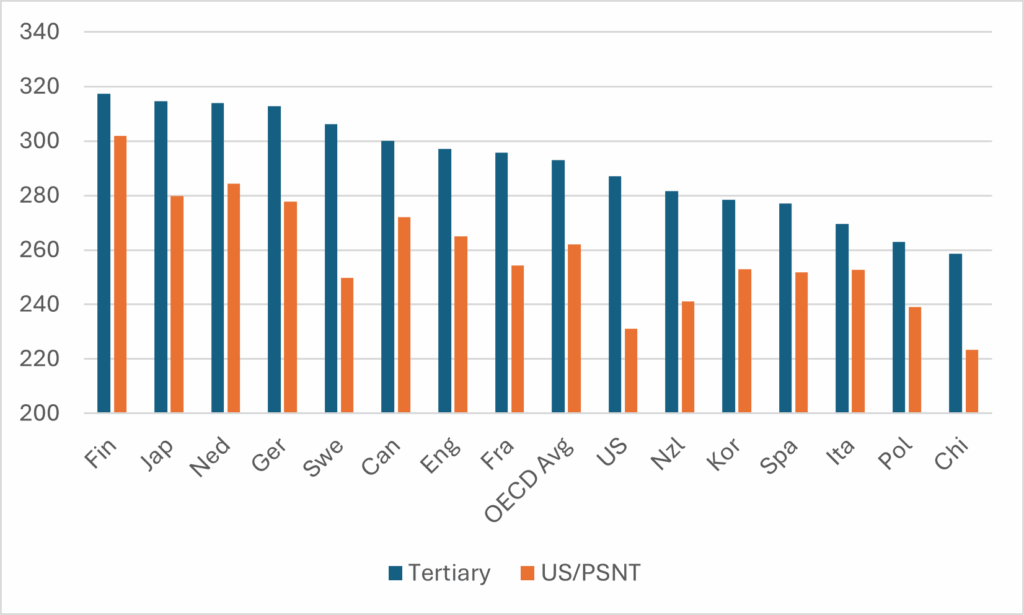

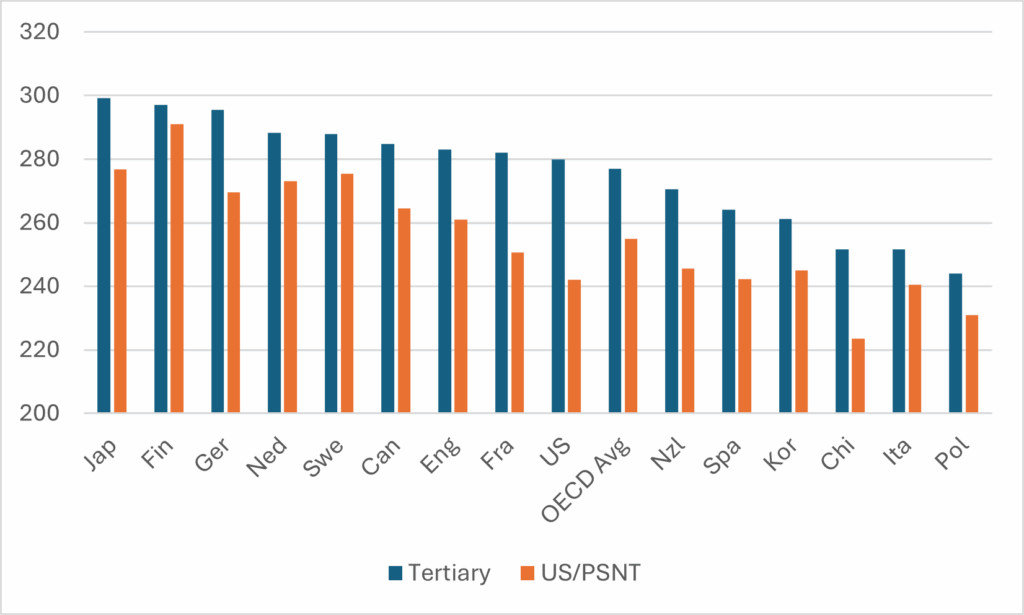

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show PIAAC results for a number of OECD countries, comparing averages for just the Upper Secondary/Post-Secondary Non-Tertiary (which I am inelegantly going to label “US/PSNT”) and Tertiary educational attainment. They largely tell similar stories. Japan and Finland tend to be ranked towards the top of the table on all measures, while Korea, Poland and Chile tend to be ranked towards the bottom. Canada tends to be ahead of the OECD average at both levels of education, but not by much. The gap between US/PSNT and Tertiary results are significantly smaller on the “problem-solving” measure than on the others (which is interesting and arguably does not say very nice things about the state of tertiary education, but that’s maybe for another day). Maybe the most spectacular single result is that Finns with only US/PSNT education have literacy scores higher than university graduates in all but four other countries, including Canada.

Figure 1: PIAAC Average Literacy Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-64, Selected OECD Countries

Figure 2: PIAAC Average Numeracy Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-64, Selected OECD Countries

Figure 3: PIAAC Average Problem Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-64, Selected OECD Countries

Another thing that is consistent across all of these graphs is that the gap between US/PSNT and tertiary graduates is not at all the same. In some countries the gap is quite low (e.g. Sweden) and in other countries the gap is quite high (e.g. Chile, France, Germany). What’s going on here, and does it suggest something about the effectiveness of tertiary education systems in different countries (i.e. most effective where the gaps are high, least effective where they are low)?

Well, not necessarily. First, remember that the sample population is aged 25-64, and education systems undergo a lot of change in 40 years (for one thing, Poland, Chile and Korea were all dictatorships 40 years ago). Also, since we know scoring on these kinds of tests decline with age, demographic patterns matter too. Second, the relative size of systems matters. Imagine two secondary and tertiary systems had the same “quality”, but one tertiary system took in half of all high school graduates and the other only took in 10%. Chances are the latter would have better “results” at the tertiary level, but it would be entirely due to selection effects rather than to treatment effects.

Can we control for these things? A bit. We can certainly control for the wide age-range because OECD breaks down the data by age. Re-doing Figures 1-3, but restricting the age range to 25-34, would at least get rid of the “legacy” part of the problem. This I do below in Figures 4-6. Surprisingly little changes as a result. The absolute scores are all higher, but you’d expect that given what we know about skill loss over time. Across the board, Canada remains just slightly ahead of the OECD average. Korea does a bit better in general and Italy does a little bit worse, but other than the rank-order of results is pretty similar to what we saw for the general population (which I think is a pretty interesting finding when you think of how much effort countries put in to messing around with their education systems…does any of it matter?)

Figure 4: PIAAC Average Literacy Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-34, Selected OECD Countries

Figure 5: PIAAC Average Numeracy Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-34, Selected OECD Countries

Figure 6: PIAAC Average Problem Scores by Highest Level of Education Attained, Population Aged 25-34, Selected OECD Countries

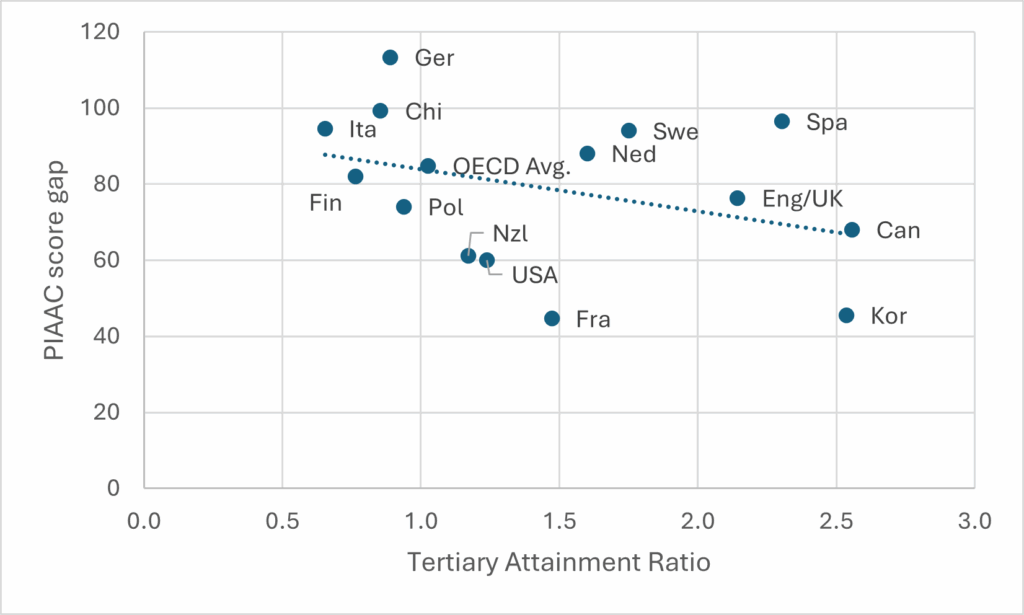

Now, let’s turn to the question of whether or not we can control for selectivity. Back in 2013, I tried doing something like that, but it was only possible because OECD released PIAAC scores not just as averages but also in terms of quartile thresholds, and that isn’t the case this time. But what we can do is look a bit at the relationship between i) the size of the tertiary system relative to the size of the US/PSNT system (a measure of selectivity, basically) and ii) the degree to which results for tertiary students are higher than those for US/PSNT.

Which is what I do in Figure 7. The X-axis here is selectivity [tertiary attainment rate ÷ US/PSNT attainment rate rate] for 25-34 year olds on (the further right on the graph, the more open-access the system), and the Y-axis is PIAAC gaps Σ [tertiary score – US/PSNT score] across the literacy, numeracy and problem-solving measures (the higher the score, the bigger the gap between tertiary and US/PSNT scores). It shows that countries like Germany, Chile and Italy are both more highly selective and have greater score gaps than countries like Canada and Korea, which are the reverse. It therefore provides what I would call light support for the theory that the less open/more selective a system of tertiary education is, the bigger the gap tertiary between Tertiary and US/PSNT scores on literacy, numeracy and problem-solving scores. Meaning, basically, beware of interpreting these gaps as evidence of relative system quality: they may well be effects of selection rather than treatment.

Figure 7: Tertiary Attainment vs. PIAAC Score Gap, 25-34 year-olds

That’s enough PIAAC fun for one Monday. See you tomorrow.