My friend Kerry left me one of her infamous voice messages today. These are the fancy kinds that go beyond voice mail, but instead show up in my text messages app, only I get to hear her voice. Apple nicely transcribes these messages for me, too, though it cracks me up what it sometimes thinks Kerry says in these messages. This time, it thought that she called me “Fran,” but instead she was calling me, “friend.”

She’s going to be on sabbatical next semester, so is wanting to get going with a note-taking application. In my over two decades in higher education, I’ve never had a sabbatical, but I imagine that if that time were to come, I would really want to get a jump on the organization side of things, as well. I’ve enjoyed following Robert Talbert’s transparency around his sabbatical as he seeks to be intentional with his sabbatical, even subtitling one of his blogs: Or, how my inherent laziness has made me productive on a big project. He also suggests that we regularly carve out time to reflect on whether where we are spending our time and devoting our attention is in alignment with the things that are most important to us.

I like reading Robert’s blogs in which he geeks out about the tools that he uses. Like me, he’s evolved what applications he uses, most recently documenting the digital tools he is using for his own sabbatical project (part 1 and part 2).

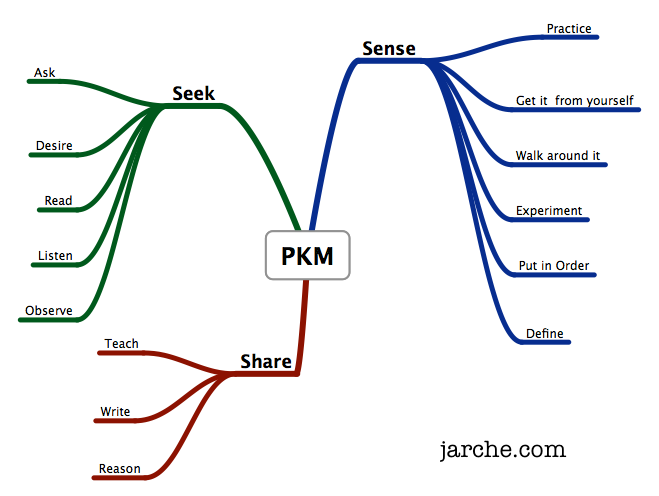

Even though Kerry asked me about my suggestions for a note-taking tool, I can’t help but zoom back out and make sure we both understand that bigger picture. I can’t really answer the question as to giving my advice related to taking notes, unless I’m sure she’s got the other vital pieces going that she will need to maximize her time. Not to mention, giving herself permission to wander and be entirely “unproductive” for at least some portions of this time away.

The Tools

For any sabbatical, I’m making an assumption that at least some portion of it will involve doing research and some writing.

References Manager

There are many good references managers out there. I haven’t changed mine really ever, since landing on Zotero many years ago. I didn’t have a references manager when doing my master’s or doctorate, so when I talk about the power of one, I tend to sound like an old person talking about having to walk uphill to get to school, both ways, with a bit of “get off my lawn” sentiment, throughout.

Hands down, if you’re going to research, or plan on doing some academic writing, it makes zero sense not to be capturing sources in a references manager. Off the top of my head, be sure you know how to:

- Add sources using the Zotero extension installed on your preferred browser. Zotero must be running in the background as an application, at least for how I have things configured on my Mac, but it will nudge you, if you forget.

- I choose to check each source, as I add it, though this isn’t necessary. Zotero is great because much of the time, it will grab the metadata associated with the item you have saved, including the author’s name, date of publication, URL, etc. However, sometimes websites don’t have their information set up such that some of the information gets missed. I would always way rather just add it, manually, in the moment I’m already on that page. Others just figure they’ll wait to see if they actually wind up citing that source.

- Cite sources within your word processor, which for me is Microsoft Word. I use the toolbar for Zotero when I need to cite a source, as I’m writing, I easily search for it, and then press enter and away I go.

- Create a bibliography using Zotero. This would have been a game changer, had I had this tool when I was in school. Some years back, they made this auto-update so each time you add a new source, your references list automatically updates, as you go. If you delete a sentence containing a citation, it is removed from your references. So cool.

Digital Bookmarks

For any other type of digital resource (ones I doubt I’ll wind up citing in formal, academic writing), I save them to my preferred digital bookmarking tool: Raindrop.io. I can’t even imaging doing any computing in any context without having a bookmarking tool available to save things to…

I’ve got collections (folders) for Teaching in Higher Ed, AI (this one is publicly viewable as a page, and as an RSS feed), Teaching, Technology, and ones for specific classes, just as an example. Take a look at my Raindrop blog post, which talks more about why I recommend it and how I have it set up to support my ongoing learning.

Note-Taking

Now we’re finally getting around to Kerry’s original question. I had to first talk about a references manager and digital bookmarks, since I wanted to ensure that she will have at least Zotero (or similar tool) for the formal, academic writing, including citing sources and doing the necessary sense-making required for academic writing.

Chicken Scratch (Quick Capture) Notes

There’s a place in many people’s lives for quick-capture notes. You’re talking to someone and they mention something you want to remember. You don’t first want to figure out where to put that information; you just want to grab it, like you might a sticky note in an analog world.

Hands down, for me, that app is Drafts.

At this exact moment, I would consider myself a “bad” Drafts user. I’ve got 172 “chicken scratch” notes sitting, unorganized. That said, I don’t put anything there that it would be terrible if the notes got “lost” from my attention for a while. These past three months, I was a keynote speaker at a conference in Michigan, and did a pre-conference workshop for the POD Conference in San Diego. Being on the road means lots of opportunities for me to hear about something, or have an idea, that I just want to quickly capture in that moment, and get back to, later.

I submitted grades late last night, so today means getting back to a more regular GTD weekly review, at which point I’ll be emptying my inboxes, including my Drafts inbox. If you’re curious about the process I use to accomplish this, I couldn’t recommend more another post by Robert Talbert: How and why to achieve inbox zero.

One other thing I’ll mention about Drafts is that it is incredibly easy to get started with… and once you’re up and running, there are a gazillion bells and whistles you could discover, should you want to get even more benefit out of it.

One fun thing I enjoy is using an app on my iPhone and Apple Watch (via a complication) called Whisper Memos, which lets me record a voice memo and then receive an email with my “ramblings turned into paragraphed articles.” However, instead of cluttering up my email inbox, I have it set up to send an email to my special Drafts email, which then sends the transcription (broken into paragraphs, which I find super handy) to my Drafts inbox, for later use.

I also keep a Drafts workspace (not in my inbox) dedicated just to my various checklists, such as packing lists, a school departure checklist (which we haven’t had to use in a long while, since our kids keep getting older and more independent), password reset checklist (where are all of the different apps and services I need to visit, anytime I get forced to reset my password for work), and a checklist for all the places I have to change my profile photo, anytime in the future I get new headshots or otherwise want a change.

Primary Note Taking Tool

Now we’re finally to the real question Kerry was asking: What app should she use to take notes? Well, as I mentioned, I actually have a fair amount of them, but since I’m at least attempting to stay focused on the sabbatical needs, I had better get back to it now.

My primary notetaking tool these days is Obsidian. Robert Talbert again does a great job of articulating how and why he uses Obsidian. A big driver for me is that if I ever want to switch things up down the road, I don’t have to worry about how to get stuff out of Obsidian. As it is just a “wrapper” or a “view” of plain text files that are sitting on my computer. If they ever decided to jack their users around by significant increases to their pricing model, without the added value one might expect, I wouldn’t be locked in at all. There are plenty of other note-taking apps that would know how to “talk” to and display the plain text files on my computer in a similar fashion as Obsidian.

That said, some people might be intimidated by becoming familiar with writing using Markdown, which is the formatting used in plain text files. Since the text is “plain,” that means you can only make something bold by using other indicators that a given word or phrase is meant to be bold. However, I find you could get up and running with the vast majority of Markdown in less than five minutes, such that this isn’t as big a barrier as it might seem.

As an example, I don’t have to type the formatting for bold, I can just high light those words and then press command-B on my keyboard, same as I would in any other writing context. Headings are just indicated by typing the number of pound signs at the start of a line. So the heading for this section of this post required four number signs, because it is a heading 4 (H4), and then I just press space and type the subheading, like normal.

That said, you couldn’t go wrong with Bear, or Craft, if you aren’t as concerned about being able to get stuff easily out of them, should you ever change note taking tools in the future.

Getting Started

The tool we select is important, yes. But more important is how we set them up to help us achieve the intended purpose of wanting a note taking tool in the first place.

Daily notes. I am not as disciplined about this as I once was, but hope to get back to doing daily notes. Carl Pullein talks about the history of the “daily note” and how to use them to keep yourself organized and focused.

Meeting notes. I am close to 100% disciplined about taking notes during meetings (really helps me stay focused, as otherwise my mind can wander quite a bit), or when attending conferences or webinars. I keep a consistent naming convention for these notes, as follows: yyyy-mm-dd-meeting-name and then move the note to a dedicated folder in Obsidian. I only move the note into the follow after I have reviewed it for any “open loops” and then captured those in my task manager.

Other writing. I’ve got folders for other types of writing that I do, as well. To me, the key is having a “home” for where things belong and to be super disciplined about consistent naming conventions, so I don’t get overwhelmed with the messiness of the creative process.

That said, Kerry will first want to play around with any note taking tool she is considering just at the note level, before she worries about how she will organize things. Otherwise, it is way too easy to get overwhelmed and not cross over the finish line of getting started using a note taking tool, consistently.

The University of Virginia Library offers ideas for how to organize research data across all disciplines. Don’t miss the part where they say to write down your organization system before you start, or in my experience, it is too easy to forget how I set things up in the first place.

]

]