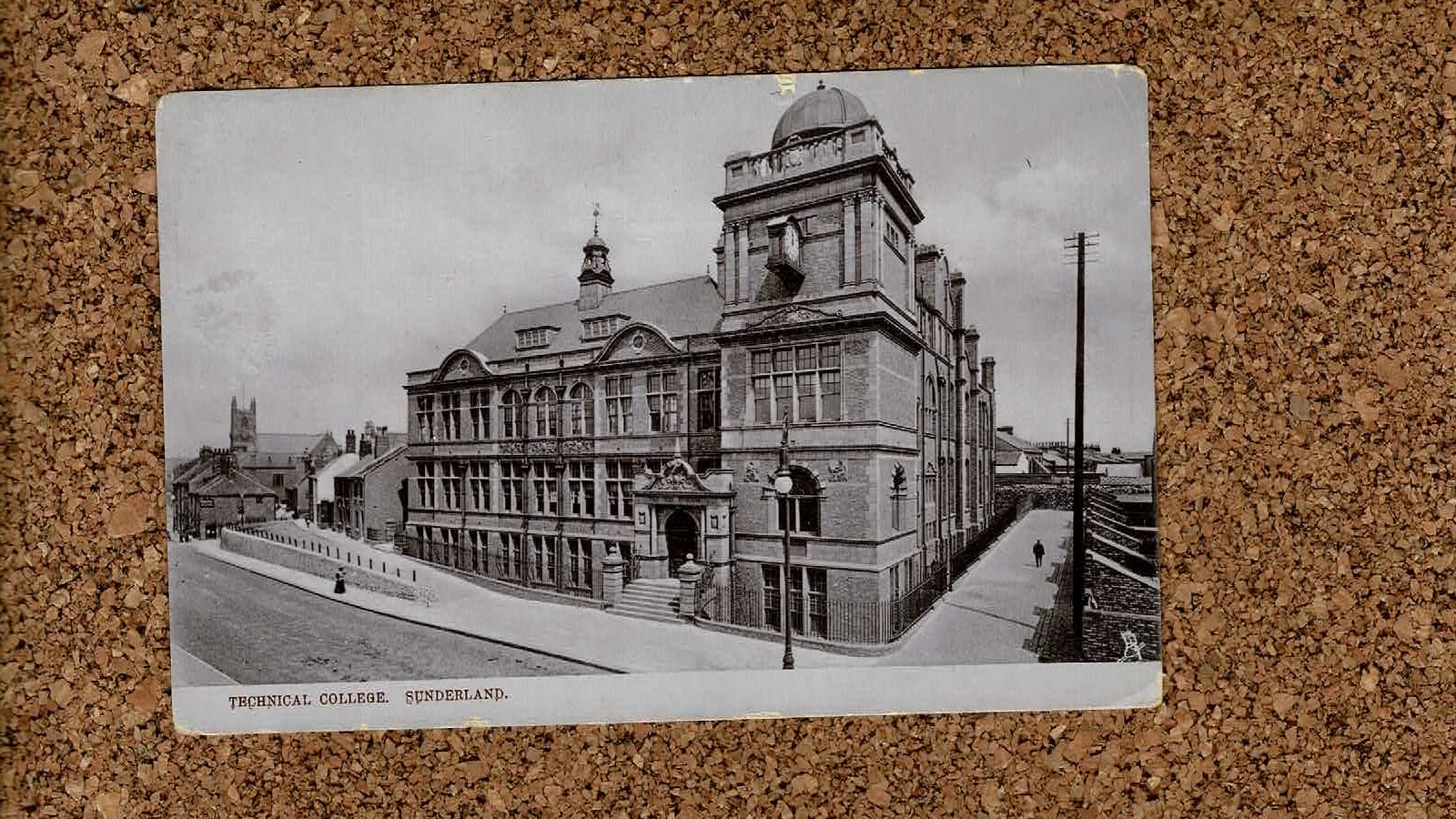

Greetings from Sunderland!

By the 1850s Sunderland’s main industries were shipping, coal and glass. And in common with other industrial towns, the need for colleges to teach beyond basic school level had been felt and addressed. There had been a mechanics’ institute, which had failed; and then the creation of a school of science and art, funded through the government scheme. There’s a most learned discussion of the Sunderland School of Science and Art in this article by W G Hall from 1966 – it was published in The Vocational Aspect of Secondary and Further Education and drew upon Hall’s Durham MEd thesis.

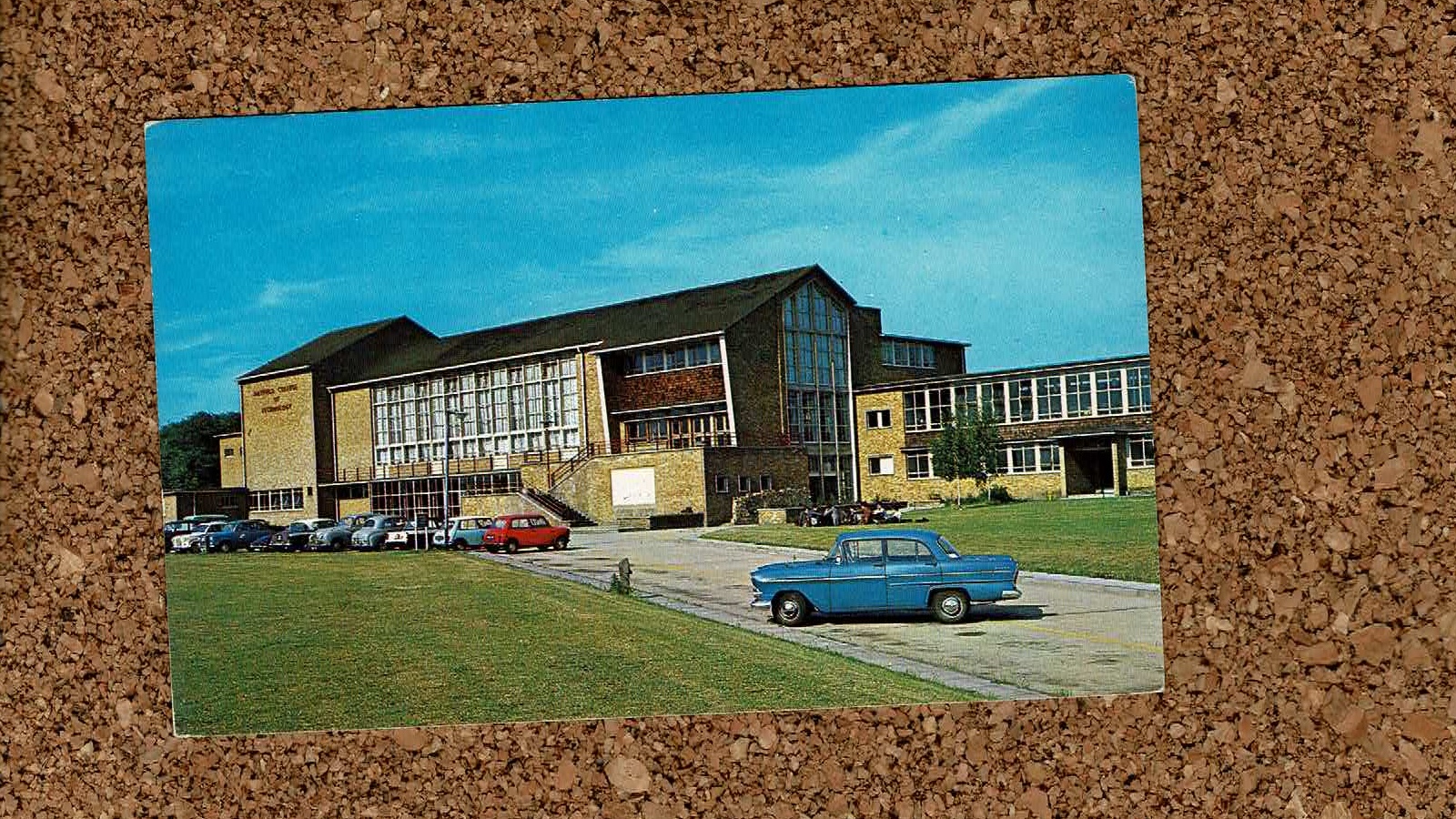

But the School of Science and Art was wound up in 1902. For the reason that the town council had in 1901 created a technical college to meet the town’s needs. The technical side of the School of Science and Art was transferred to the new college after it had been running for a year; the art side was hived off into a newly established Sunderland School of Art.

The technical college was absolutely geared to the town’s industrial needs. Alan Smithers reports that in 1903 “heavy engineering and shipbuilding industries in Sunderland tried an arrangement whereby apprentices were released to the local technical college for six months each year over a period of several years.” While this was not the very first sandwich course – which may have been in Glasgow or in Bristol, 60 or 25 years previously, depending – it was a new model for technical colleges, and was soon copied in Wolverhampton, Cardiff, and at the Northampton Polytechnic, London.

From 1930 students were able to study for degrees: in applied sciences, from Durham University; in pharmacy, from the University of London. And in 1934 London also recognised the college for the BEng degree.

In 1969 the technical college, the school of art, and the Sunderland Training College (which had been established in 1908 and which operated from Langham Tower) were amalgamated to form the Sunderland Polytechnic. Educational innovation continued, with the country’s first part-time, in-service BEd degree being offered.

In 1989 the polytechnic – along with all others, it wasn’t just a Sunderland thing – moved out of local authority control to become a self-governing corporation, following the 1988 Education Reform Act. The Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette ran an eight page supplement on Monday 3 April to celebrate. Features included:

- a foreword from the Polytechnic’s Rector, Dr Peter Hart. (You can see a picture of him below, sat at his desk. 1989 and no computers. Sic transit gloria mundi.)

- a sport-council funded project to promote inclusion of people with disabilities in sports

- the polytechnic’s autism research

- a photo of the polytechnic’s switchboard operators, with their new computerised system which enabled direct lines to extensions within the poly

- the polytechnic’s knowledge exchange work

- a picture of an Olympic athlete (Christina Cahill, fourth at the Seoul Olympics women’s 1500m) joining student services

- the faculty of technology

- an article written by the dean of the new faculty of business, management and education

- pharmacy and art

- the Japanese language centre at the polytechnic

- a charity based at the polytechnic looking at medicines for tropical diseases.

There’s a variety of stuff here, and what strikes me is the fact itself that the local paper regards the poly as a local amenity. There was clearly a felt connection between the local paper and this very big local institution, and pride at what it did.

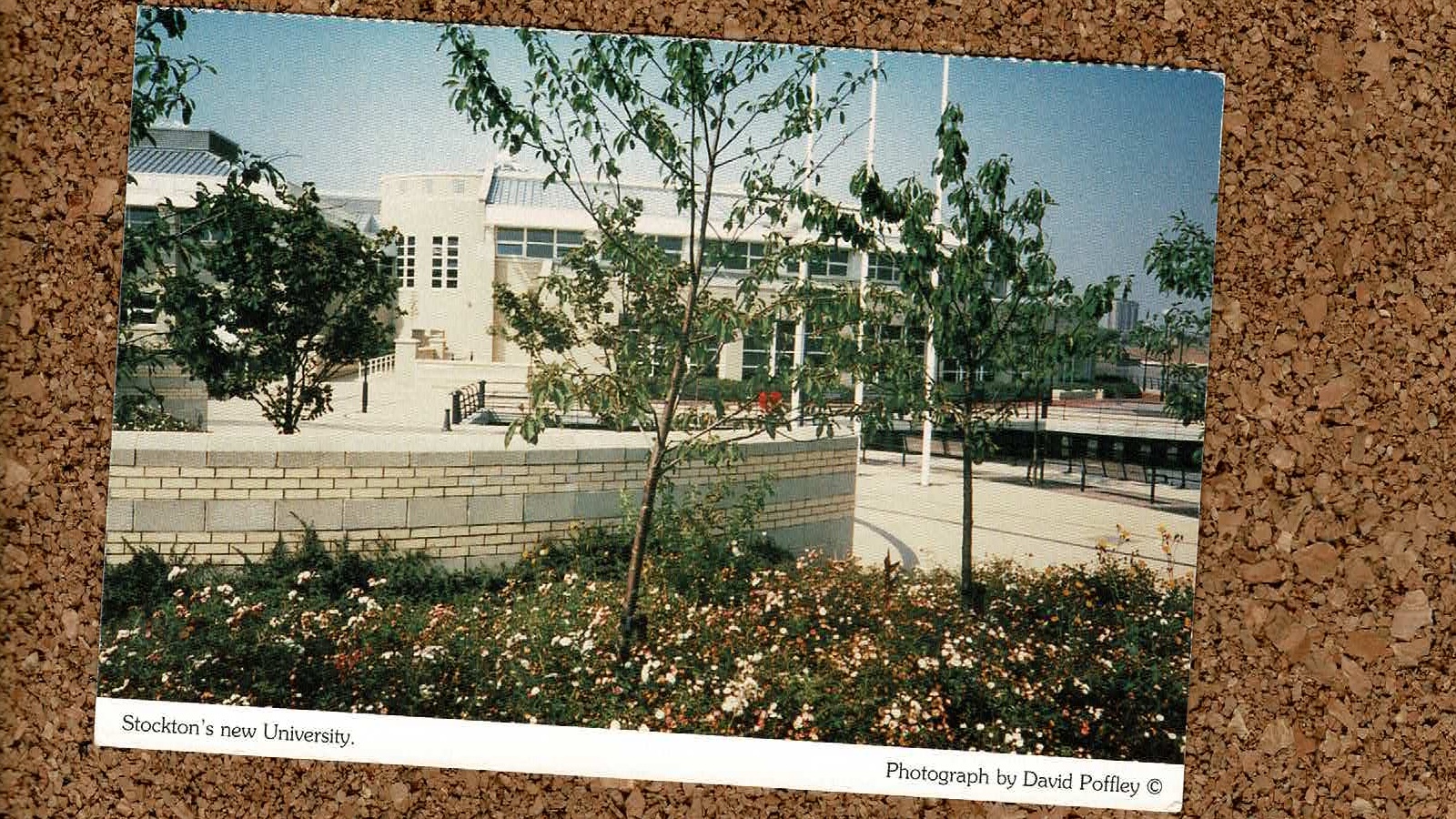

In 1992 the polytechnic became the University of Sunderland. It now has campuses in London and Hong Kong as well as in Sunderland, and since 2018 has had a medical school.

Alumni include Olympic athlete Steve Cram and current Guyanese President Irfaan Ali.

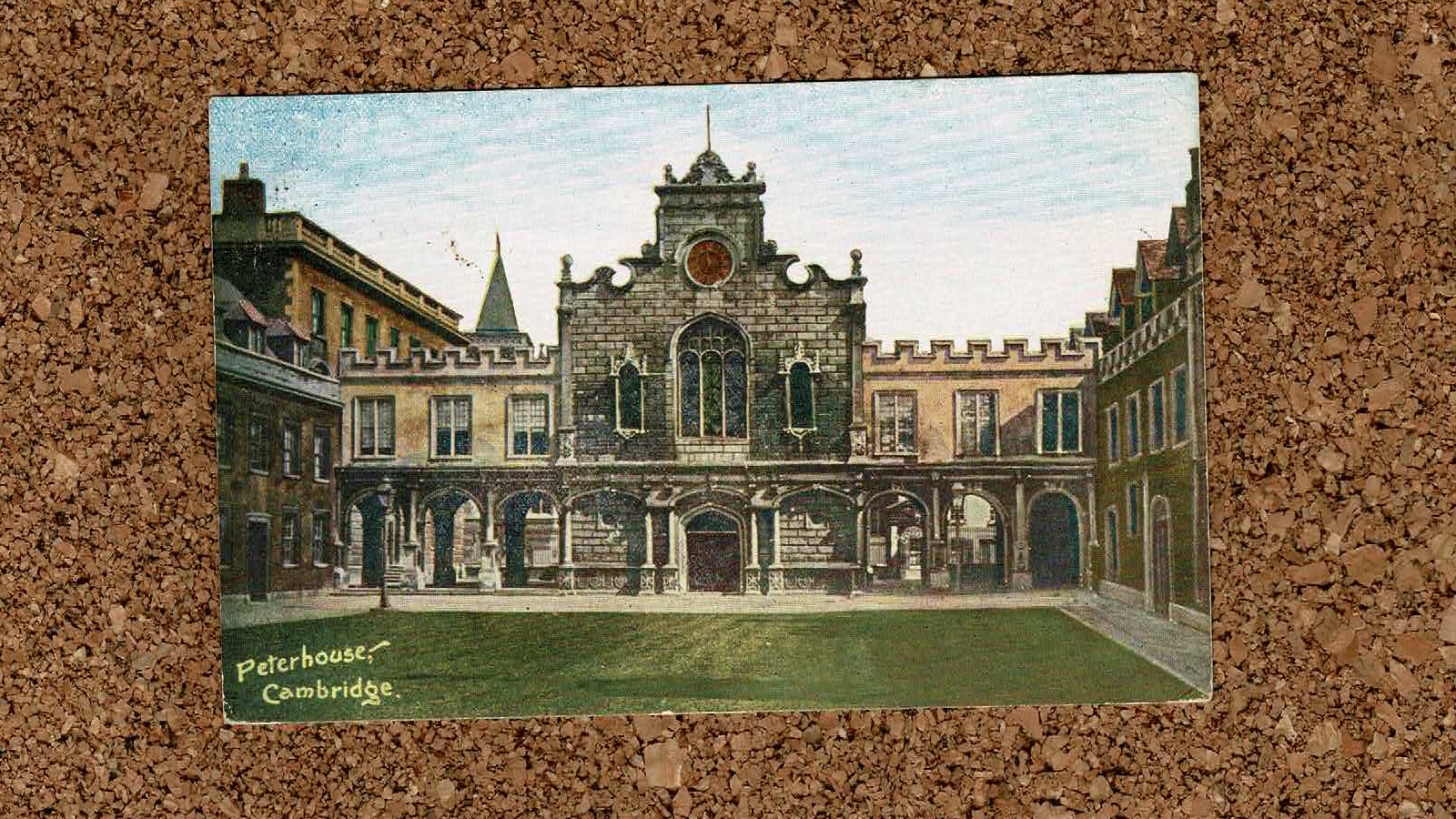

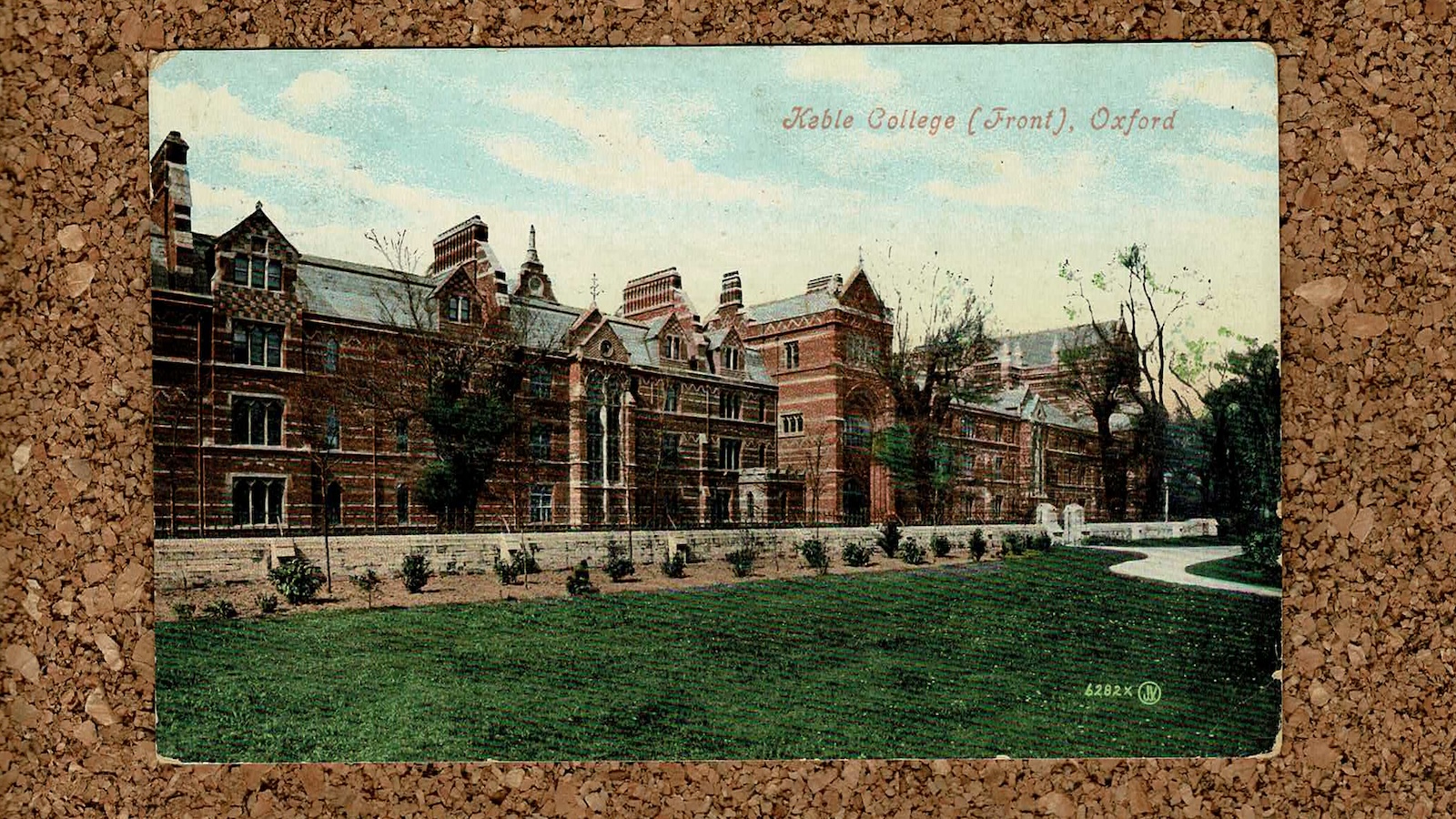

Here’s a jigsaw of the postcard – it’s unsent and undated but I would guess it is from before the first world war, as it was printed in Berlin.