In about 520CE, or so the story goes, Radegund was born, daughter of Bertachar, one of three brother kings of Thuringia.

Uncle Hermanfrid, one of the other brothers, killed Bertachar; Radegund moved into his household. Hermanfrid allied with another king, Theuderic, to defeat Radegund’s other uncle, Baderic, and thus became sole King of Thuringia. And in so doing he reneged on an agreement with Theuderic.

I hope you’re paying attention, because there’ll be a short test later.

Now Theuderic was not the kind to forget a slight, and in 531, when Radegund was 11, he invaded Thuringia, with his brother Clothar. They defeated Hermanfrid, and Ragemund was taken into Clothar’s household. She lived in Picardy until 540, when Clothar married her, bringing his total of wives to six. (The other wives were Guntheuca, Chunsina, Ingund, Aregund and Wuldetrada, just in case you think I’m making this up.)

![]()

In 545 Clothar murdered Radegund’s last surviving brother, and that was clearly the last straw, as she fled. She sought the protection of the church, and Medardus, Bishop of Noyen, ordained her as deaconess. In about 560 she founded the abbey of Sainte-Croixe near Poitiers, and she died in 567, having reputedly lived an austere, ascetic life, renowned for her healing powers. Or so the story goes.

Now fast forward 600 years or so. Malcolm IV, King of Scotland and Earl of Huntingdon, visited Poitiers, the site of the cult of the now-sanctified Radegund. He gave ten acres of land to found a priory, dedicated to St Mary and St Radegund. And this land was in what would in time become central Cambridge.

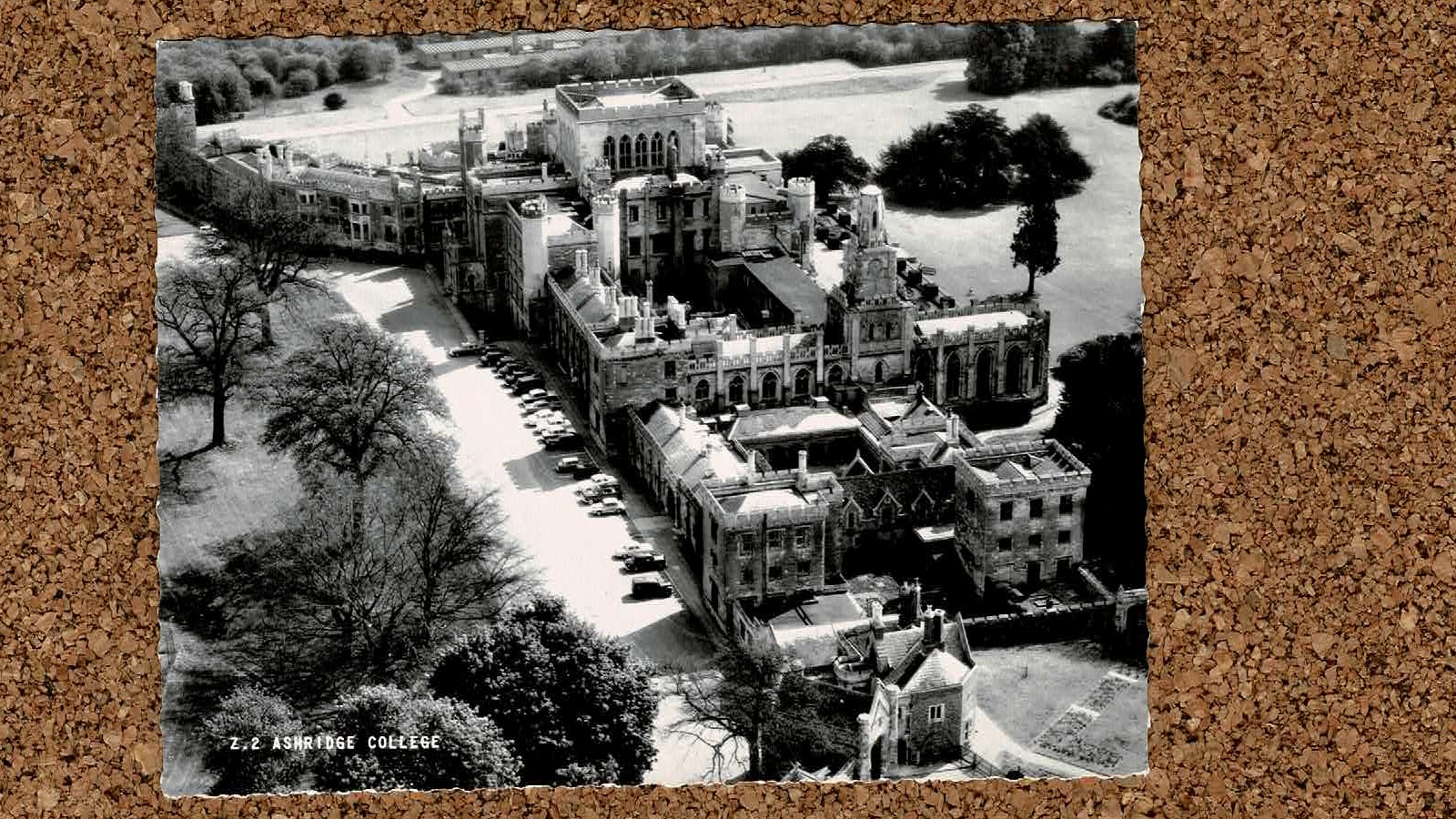

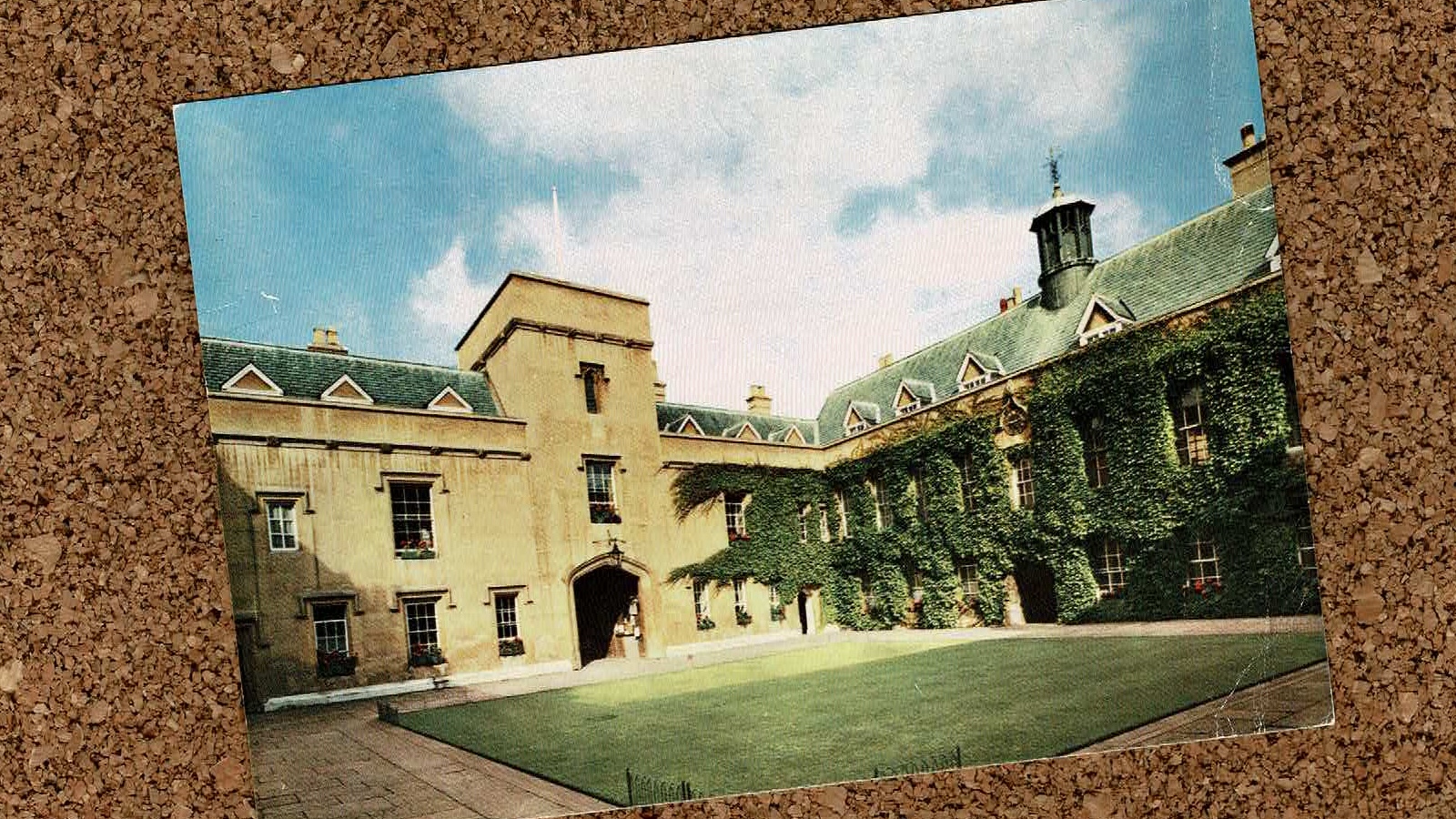

Now fast forward another 300 years. The priory now had a – ahem – reputation. John Alcock, Bishop of Ely, in whose see the priory sat, was given permission by Pope Alexander VI and King Henry VII to dissolve the priory. This was in 1496; the later description of the priory as a “community of spiritual harlots” may have been the cause; it may also, of course, have been a post facto justification. In any event, the priory was dissolved and a college founded in its place. The College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge, which is now more commonly known as Jesus College, Cambridge, took over the priory buildings, and away it went.

Bishop Alcock, by the way, gave the college its arms: the three cocks’ heads play on his surname. No sniggering at the back there.

For hundreds of years Jesus was, in essence, a training college for clergy, staying small. But in 1863 Henry Morgan was appointed tutor of the college, and set about his duties with energy. The railway boom at the time meant that some of the original priory lands could be sold, bringing in cash with which Morgan expanded the college: by 1871 there were four times as many students as ten years previously; by 1881 the college had nearly doubled in size again from 1871. And these students would not be confined to those seeking a career in the Church of England.

Let’s have a look at some Jesus College people. (What’s the correct term? Jesuits is logical but it really does have a more specific meaning. Jesusites? Jesusians? I bet there’s a correct term, and I bet someone will comment to say.)

A good place to start is Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury at the time of Henry VIII, and architect of the English reformation. Cranmer may have (but probably didn’t) attended the college as a student, but he was certainly reader in divinity at Jesus from 1517 to 1528. He didn’t keep strong connections to the college after moving into court circles as archbishop, but as he was ultimately executed as a traitor (he backed the wrong team in the post-Edward VI power struggle) this may have been no bad thing, for the college at least.

Let’s then move on to Laurence Sterne, student at the college 1733–37. He became a clergyman, but no-one remembers him for this. Because he arguably invented the English novel, with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman published between 1759 and 1767. If you don’t know it, have a read; it is well worth it. It may change your opinions about just how modern modern writing is.

Next in the roll of honour is Thomas Malthus, student of the college 1784–88 and fellow 1793–1804. As an economist Malthus was influential. In his Essay on the Principle of Population as it Affects the Future Improvement of Society he argued that population growth was unsustainable, because demand for food would inevitably outstrip supply. It is worth noting that the world population at that time was about 800 million; it is ten times that today. And while food is not fairly distributed across the world, neither is there a population crash as Malthus argued there would be.

And now let’s move on to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, romantic poet and opium addict, author of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan. Coleridge was a student at Jesus. He developed his opium habit while at college, and in his third year dropped out to join the army, under the assumed name of Silas Tomkyn Comberbache. His brother had to pay a bribe to get him out of the army, and although he returned to Cambridge thereafter he never quite graduated.

In 2019 Jesus appointed its first female master, Sonita Alleyne, having first admitted women as students in 1979. Alleyne was also the first black head of an Oxbridge college, preceding Valerie Amos at University College, Oxford by a year. More generally, the college has a very good run through its history here.

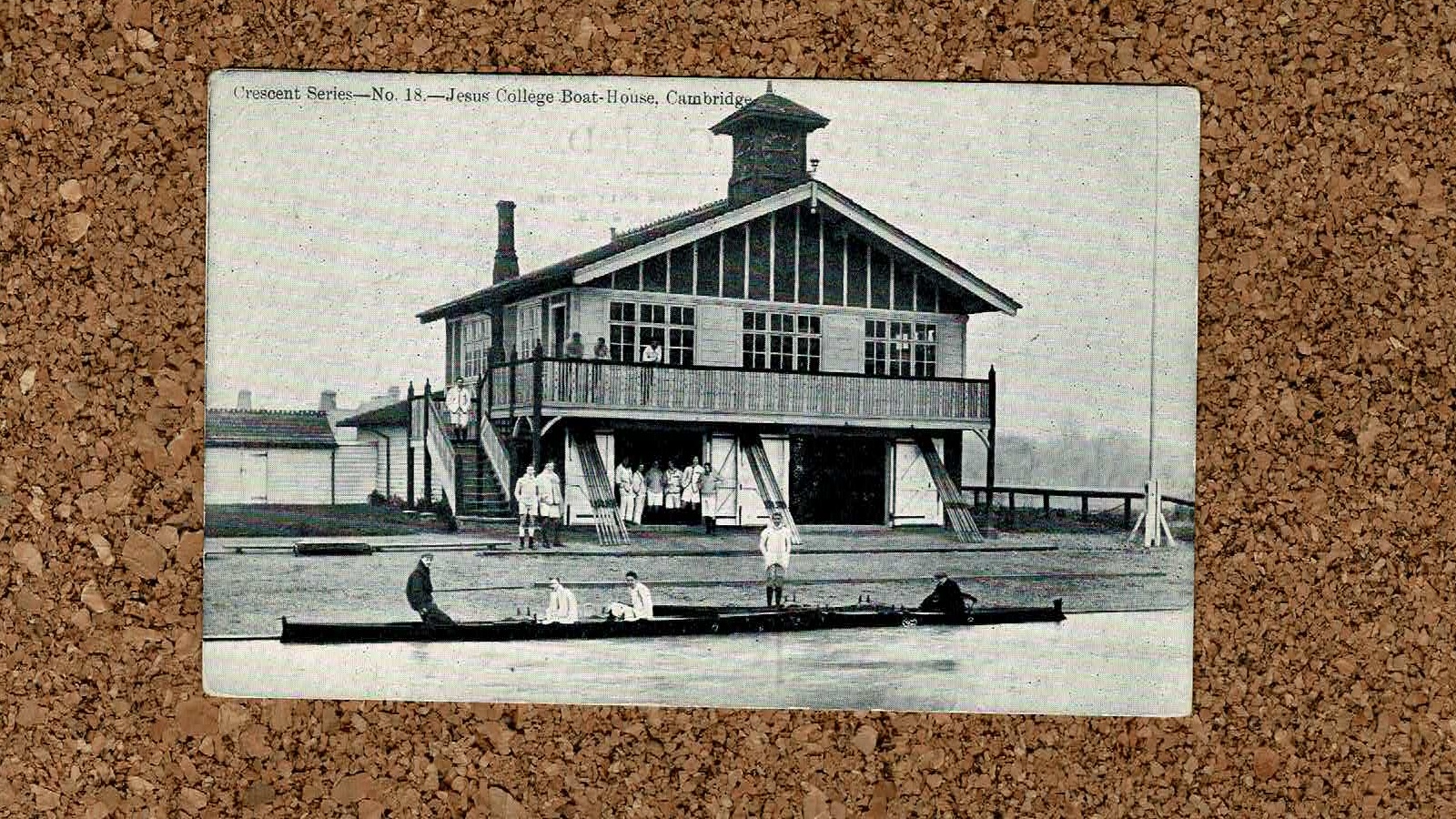

Jesus is a sporty college, and its boat club is very strong. It holds the most headships of the river in the May and the Lent bumps, across both men’s and women’s boats. (I tried to explain about Cambridge rowing a while ago – here’s the link in case you’re interested.)

And here’s a jigsaw of the card – hope you enjoy it!