Paul T. Corrigan teaches at The University of Tampa. He is currently writing a book on teaching literature. He has published on teaching and learning in TheAtlantic.com, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed, College Teaching, Pedagogy, Reader, The Teaching Professor, International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, and other venues. He has a PhD from the University of South Florida and a MA from North Carolina State University. More at paultcorrigan.com. Follow on Twitter at @teachingcollege.

Category: Scholarship on Teaching and Learning

-

Disagreeing with(in) Antiracism | A Conversation with Erec Smith

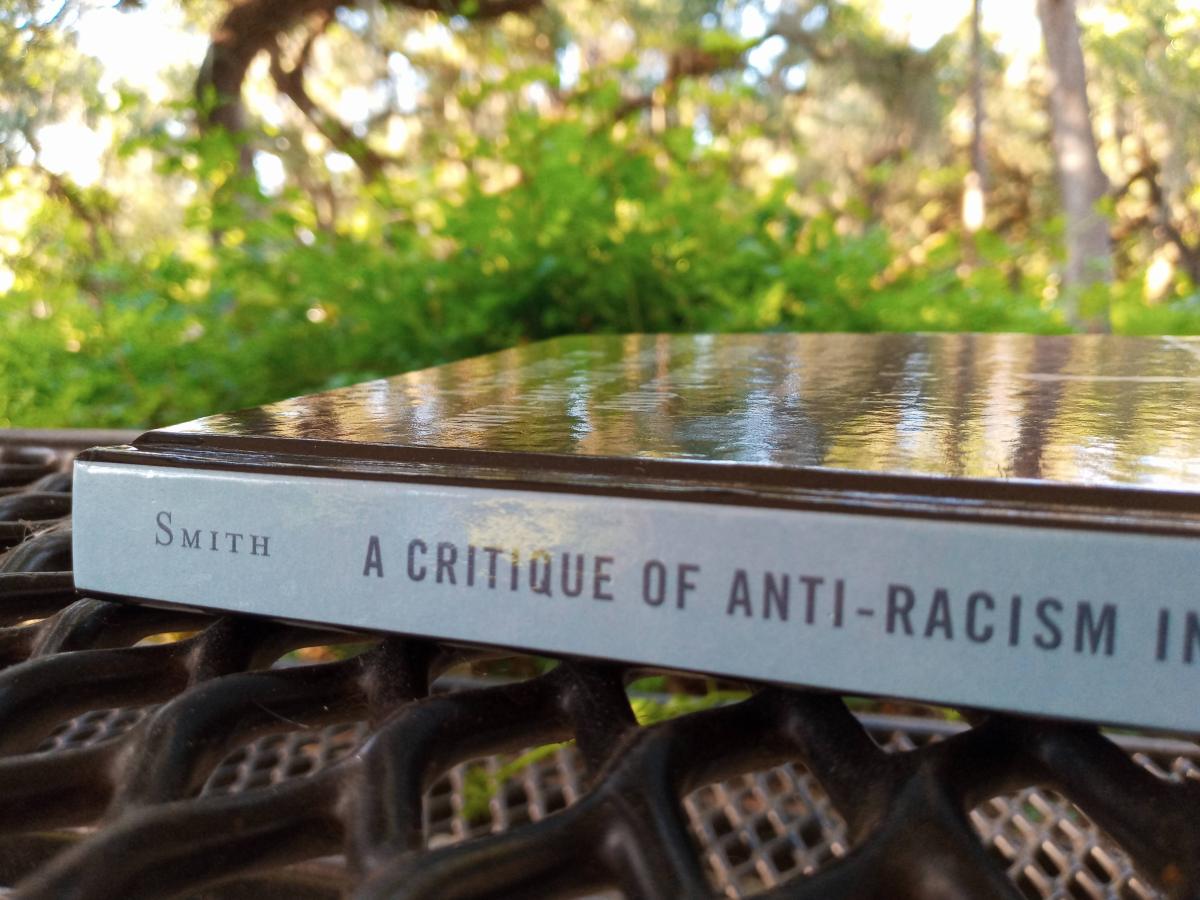

I sat down with Dr. Erec Smith, Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at York College, to discuss his book A Critique of Anti-Racism in Rhetoric and Composition: The Semblance of Empowerment (Rowman and Littlefield 2019). While Erec, to be clear, opposes racism itself, he also opposes the forms of antiracism he believes constitute the current antiracism movement in writing studies. To be equally clear, I disagree strongly with most of Erec’s take. With one key exception: I agree with Erec about the value, the vital necessity, of disagreement itself.

In the preface, Erec writes: “I can only tell you that I seek truth and justice and I write this book solely from that interest. I genuinely hope people will read, engage, and critique it to their heart’s content. I want to know why they agree or disagree with my conclusions. One of the main motivations for this book is to encourage a productive and generative approach to disagreement and discourage attempts to silence, shut down, or shame others into submission” (viii).

My own desire to engage disagreement productively is specifically why I read Erec’s book and why I asked him to have this conversation with me. Now, I don’t think that all disagreements are automatically productive to engage with–and the topic of antiracism seems to draw more than its share of counterproductive ones. Indeed, when we reached the end of our talk, I felt uncertain about just how productive ours disagreement had been. (And Erec may well have felt likewise.) But nonetheless, I think, I hope, I want to believe, that the work of disagreeing together is and can be an important aspect of being and becoming more effectively antiracist. So this conversation is one effort at that, and, disagreements aside, I’m grateful to Erec for participating with me.

If you see the role of disagreement in antiracism differently, well, I’d love to talk with you about that.

-

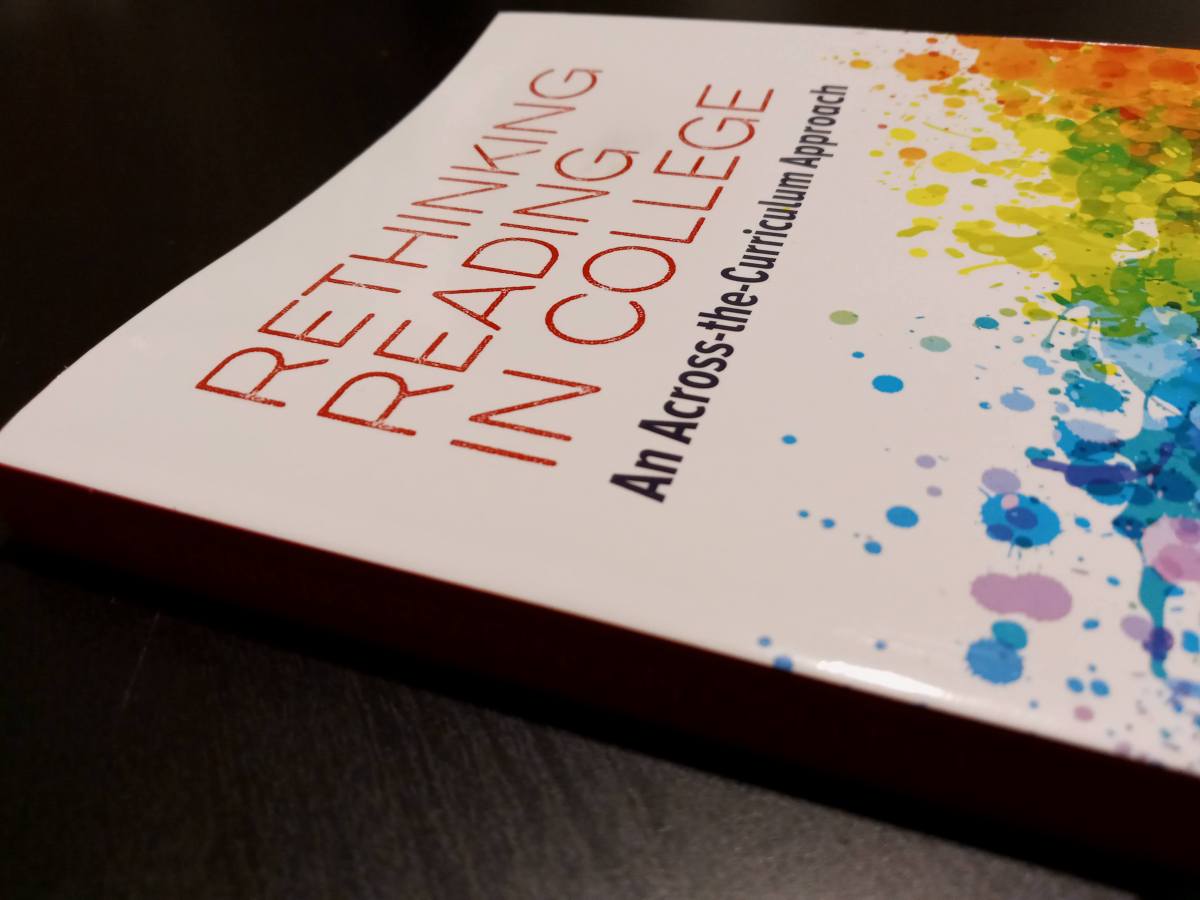

Now You’ve Read Those Things, Too | A Conversation with Arlene Wilner

I sat down with Dr. Arlene Wilner, Professor of English at Rider University, to discuss her new book Rethinking Reading in College: An Across-the-Curriculum Approach. Central to her approach is the idea of rhetorical reading: we ought to teach students, in any discipline, to approach texts not as freestanding and homogenous info blocks but as written by specific people in specific contexts for specific purposes and constructed such that the parts relate to the whole to support those purposes. In other words, to use terms Wilner borrows from John Bean’s Engaging Ideas, texts don’t just say things, they also do things. A sentence does something in a paragraph, something different than other sentences. A essay does something in a larger discussion, something different than other essays.

We also discussed the importance of background knowledge for reading comprehension. “It takes knowledge to learn,” she says. Now, I’ve long been wary of too great an emphasis on students gathering background knowledge, since, in my mind, that impulse can lead to a sort of teaching-as-coverage approach, where we spend all our time giving students background knowledge they never get around to actually applying to anything. But I’m coming around to Wilner’s point, which is supported by psychological studies on the matter (she cites, for instance, Daniel T. Willingham’s The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads). The key seems to be timing and balance: it can’t be all content or all skills but both.

Stressing background knowledge, Wilner acknowledges–especially the idea that the background knowledge most important for students tends to be common cultural knowledge–could be seen as supporting regressive notions about what “common cultural knowledge” is or ought to be (i.e., traditional notions of canon). But this doesn’t have to be the case. We can a diverse set of texts in common. As one example she shares: when her students read Martin Luther King’s Letter from “Birmingham Jail” and recognize allusions to Socrates and others texts, they get excited, knowing what he’s talking about. She tells them, “Well now you’re part of the conversation, because you’ve read those things too.”

Wilner wants more from and for students than merely connecting with and responding to the texts they read. Though that is meaningful, she wants them to go deeper, see layers, interrogate their immediate responses. It’s easy to “translate” texts “to something that’s comfortable and familiar to us,” she says, even if that translation misses what the text is actually saying. But it’s “respectful” of students and of their intellectual abilities to ask them to do more, to help them do more. Students ought not go into college thinking, “I’m going to have my existing feelings beliefs ratified” but instead, “I’m going to have them shaken up.’” Some hard, important, scaffolded reading offers a lot in that direction.