In 1994, the year that HESA was born and we started to count those with degrees from former polytechnics in the stats, about 225,000 full-time home-domiciled students graduated with a first degree in the UK.

Today the Russell Group enrols about 350k. Funny that those who say too many people go to university tend to stay tight lipped about that part of the sector’s “dilution”.

Ten years later, then funding council boss Howard Newby said:

[T]he English—and I do mean the English—do have a genius for turning diversity into hierarchy and I am not sure what we can do about that, to be quite honest. It is very regrettable that we cannot celebrate diversity rather than constantly turning it into hierarchy.

The switch of circa 125,000 students from poly to university in the early 90s was one of the signature moments of the status/sorting panic that has accompanied the expansion of higher education over time.

The story runs something like this. Access to university has never been evenly distributed across the social-economics. And having a degree seems to bestow upon graduates socio-economic advantages.

So over the long-run, rather than doing the hard yards of making entry distribution fairer – which, whatever method is used, necessarily involves saying “no” to some who think they have a right to go – the easier thing has always been to say “yes” and expand instead.

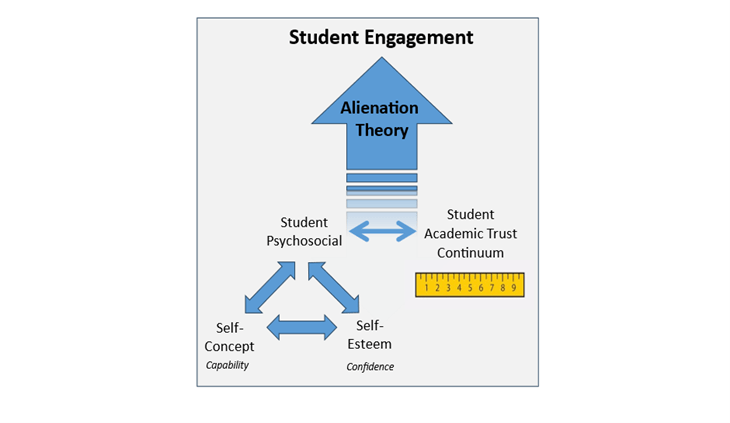

Hence when in 2018 OfS had a choice between Option 1:

![]()

…it obviously couldn’t persuade ministers to front out Option 1. So everyone let Option 2 happen instead – only without the money to support it. And now look at the mess we’re in.

![]()

Option 2 – whether applied to the whole sector or just the elite part – creates a problem for those who enjoy the relative rarity of the signalling. The signal is less powerful, partly because there are few who look back on their time at university and think “maybe if it was truly meritocratic I wouldn’t have made it in”.

It also ought to be expensive to expand – so over time both universities and their students are instead expected to become more and more efficient, or fund participation through future salary contributions to pay for the expansion.

And if overall participation levels off, Option 2 applied just to the elite part of the sector yanks students away from everywhere else – with huge geographical and social consequences along the way.

There is a human capital upside of mass participation. The better educated the population, the more inventive and healthy and happy and productive it will be in general. But without other actions, that doesn’t address the relative inequalities of getting in or getting on.

Onwards and upwards

The phrase “social mobility” doesn’t actually appear in the 2024 Labour Manifesto – but it’s lurking around in the opportunity mission as follows:

We are a country where who your parents are – and how much money they have – too often counts for more than your effort and enterprise… so breaking the pernicious link between background and success will be a defining mission for Labour.

Good luck with that. Part of the question for me that surrounds that is the scale of that challenge insofar as it concerns higher education – and what is coming soon in the stats that will make that easier or harder.

For the past few decades, different iterations of the “efficiencies” needed to massify – which focussed largely on the transfer of the costs of participation from state to graduate – have had three core features designed to reconcile the expansion and efficiency thing with the goals of social mobility before, during and after HE:

- Initiatives (a mix of sticks and carrots, inputs and outcomes and getting in v getting on) aimed at broadening the characteristics of those getting in into higher education

- No upfront participation costs via loans to students for maintenance and tuition – so being in it felt “equal”

- Loan interest and income-contingent repayment arrangements designed to redistribute some of the relative economic success to the less successful

Taken together, the idea has been that accessing the signalling benefits will be easier via expansion and fairness fixes; that the experience itself resembles the “school uniform” principle of everyone having a fairly similar experience; and then that those who reap the economic rewards shoulder the biggest burden (and in that a burden a bit bigger than it actually cost) in paying for it all.

You tackle inequality partly through opportunity, and partly through outcomes – the rich pay more both than others and more than the actual cost. So central was redistribution to the design of the fee and loan system in the last decade that the government announced and formally consulted on a plan for early repayment mechanisms to stop people on high incomes being able to “unfairly buy themselves out of this progressive system”.

But a decade on, the government is in a real bind. The initiatives aimed at broadening the characteristics of those enrolling into higher education look much less impactful than just expanding – especially in “high tariff” providers.

The cost of living – especially for housing – is wrecking the “school uniform” principle unless we were to loan students even more money – which has its… costs.

And having reduced interest on student loans to inflation – paid for by a longer loan term – it’s hard to think of a more politically toxic move than slapping it back on, however redistributive it will look on an excel sheet.

A bigger mountain to climb

That all exacerbates the social mobility challenge. Students cluster into the Russell Group because that group of providers now has the same “meaning” for the press and parents that “university” had prior to 1992.

Whether in the Russell Group or not, the differential student experiences of haves and have-nots (both inside and outside of the curriculum) will show up both in their actual skills and what they can “sell” to employers. And the most successful graduates from the most attractive-sounding universities will pay less for university across their lifetime, while everyone else will pay more.

In a way though, even thinking about social mobility or the redistributive graduate contribution scheme in terms of relative lifetime salary is the biggest problem of all. Because given what’s coming, it really should be the least of our worries.

Since Tony Blair increased tuition fees to £3,000, above-inflation house price growth has delivered an unearned, unequal and untaxed £3 trillion capital gains windfall in Britain. 86 per cent above inflation house price growth over the past 20 years has delivered capital gains on home owners’ main residences worth £3 trillion – now a fifth of all wealth in Britain.

The value of household wealth stood at around three times the value of national income throughout the 1960s and 1970s – but since the 1980s, the rate at which households have accumulated wealth has accelerated, outpacing the growth in national income, so that the stock of household wealth was estimated to be 7.6 times GDP at the end of 2020.

Wealth matters. For those who have accumulated it, it provides a better ability to absorb shocks to income, easier access to lower-cost credit, and facilitates investment in significant assets such as housing. But it’s not equally held.

Wealth is about twice as unequal as the income distribution, and because growth in wealth is outpacing growth in household income it is harder for those currently without it to accumulate it, and enjoy the same benefits outlined above – because as the value of assets rise relative to income, it becomes harder for someone to “save” their way up the wealth distribution.

The least wealthy third of households have gained less than £1,000 per adult on average, compared to an average gain of £174,000 for the wealthiest ten per cent. Gains have been largest in London, where on average people have gained £76,000 since 2000, and smallest in the North East of England, with an average gain of just £21,000.

As Robert Colville points out in The Times:

We have come to realise that what is really dividing our society, as that £5.5 trillion starts to cascade down the generations, is not the boomers’ greed but their love.

There’s an age aspect to the inequality – those aged 60+ have seen the biggest windfalls at around £80,000 on average – compared to an average of less than £20,000 for those under 40 years of age. But that age aspect also points to something hugely important that’s coming next – because eventually, those older people will die – and who they transfer their wealth to, and what it’s invested in, will matter. Because not only does wealth inequality dwarf wage inequality, it also predicts and drives it.

Student transfers

Here thanks to the Resolution Foundation we can see how intergenerational transfers (both gifts and inheritances) will become increasingly important during the century, as older households disperse their wealth at death via inheritances. It estimates that those transfers are set to double over the next 20 years as the large baby-boomer cohort move into late retirement – and it is likely that more wealth will be dispersed by these households while they are alive through gifts.

![]()

And it’s when that ramps up that the interaction with any tuition fee system that will really start to matter.

Since 2015/16, DfE figures for England tell us that between 10.1 and 13.6 per cent of entrants at Level 6 have self-funded. Some of that will be PT/CPD type activity, some of it students running out of SLC entitlement, and some not drawing down debt for religious reasons – but most will be people who can just afford it.

Of course what a fixed-ish percentage hides a bit is the number growth – if HE participation has been growing “at the bottom” of the social-economics, a fixed-ish percentage means that more on equivalent incomes are paying upfront. In 2022/23, a record 54,700 entrants were marked up as “no award or financial backing”.

In the original £9,000 fees system, it made little sense to opt-out of student loans – because the vast majority never paid it back in full by design. But now with a cheaper (in real terms) tuition fee, a frozen repayment threshold and an extended term of 40 years, the calculation has changed – suddenly it makes much more sense to avoid the debt if you can.

And so given that paying for your younger relatives’ tuition fees represents a way of investing some of that inheritance in way that avoids inheritance tax, we’d have to assume that unchecked, not only will richer graduates in the loan scheme get a much better lifetime deal than they did a few years ago, more and more won’t be in the scheme at all.

![]()

(The green line is the system we had for most of the last decade – the grey line the system the Conservatives slipped past everyone on their way out).

Even if every penny of an inheritance was drained away on paying for HE upfront, if we compare two graduates – one with 40 years of graduate repayments ahead of them, and one without, it doesn’t take long to clock how impossible social mobility becomes for otherwise notionally equal graduates.

Then assume that those getting their fees and costs paid for them while they’re a student are clustered into the Russell Group and its signals already – and lay on top of that the fact that those without a windfall coming are more likely to be those with a pretty thin “student experience” and so without the skills or cultural capital to cheat the socio-economic odds, and you pretty quickly need to give up and go home.

The problem that that all leaves is pretty significant – partly because wealth inequality is already more stratified than income, partly because it drives the type and value of HE experience a student might have, and partly because HE participation has a much better track record at delivering salary gains and salary redistribution than it does at delivering wealth gains or wealth redistribution.

Put another way, it might be a rite of passage, and it might be good to have a better educated population, but without the prospect of it delivering social mobility, it will lose both real and symbolic value.

Hierarchy or diversity?

So in reverse order, what can be done? On the way out, if there must be a graduate contribution system, not only does it have to return to attempting to redistribute from the richest to the poorest, it has to do so by expecting a fair chunk of that boomer windfall to fund some redistribution.

An above inflation interest rate has to return – and upfront fee payers shouldn’t be able to just buy a better education for themselves, as they can in the US – they should be expected to contribute more into the pot for everyone’s benefit. Higher fees, but only for for upfront payers – DfE needs to dust off that consultation from the last decade, and fast.

During, we’ll need to redouble efforts to re-establish at least a notional run at the school uniform principle – carefully calibrating student income and experience to return to a baseline where everyone experiences something similar.

Some of that is about reducing the costs of participation rather than loaning more money to meet them, some is about defining a contemporary student experience so that those who need to work can do so with dignity while extracting educational value, and those that don’t are expected to. It’s also about a credit system that recognises the educational value of extracurricular activity – so that everyone has time to take part in it.

Then on the way in, we need more mixing – we do need Scenario 1 to return as a much tougher target.

As well as that, the clustering up the league tables as a way of avoiding harder questions about access in our elite institutions almost certainly needs to stop. Taken to its logical conclusion, in a couple of decades there will only be 24 universities left (and in the minds of the press and parents, we’re arguably already there) – but if Labour facilitates only 19 cities having students and graduates in them, both it and everywhere else is doomed.

Labour, in other words, has to start saying no:

- It could say “no” to current university growth altogether, letting further education grow to soak up demand as polytechnics did when universities were capped in the 80s;

- It could say “no” to any more university growth in current locations, allowing expansion into other places with all the economic and social benefits that would bring;

- It could say “no” to any more “residential” places at universities, causing colleges and universities to become more comprehensive as they rush to make commuting more normal;

- Or it could say “no” to “low value” courses, on the assumption that supply and then demand will flow into “high value” ones – if, of course, it could find a credible way of differentiating between the two.

Part of the balancing act to choking off clustering is one other thing that should matter to Labour. The scandal isn’t that applicant X can’t quite get into the Russell Group with 3 A*s. It’s that we still have a system that somehow writes off the student and the university they attend if they don’t.

Making it much more attractive to commute (coupled with a domestic Erasmus), talking up not just alternatives to university but universities that aren’t the Russell Group, abolishing the archaic degree classification system, ripping up all the quality systems that have singularly failed to “assure” the press and the public that quality can be found elsewhere, and forcing through some institutional subject specialisms (and obvious vocational excellence) within the system would all help.

Do all of that, and maybe one day, a senior figure in HE might be able to claim that mass higher education – and all the rich benefits it brings – both survived and thrived because it finally found a way to celebrate diversity rather than forever turning it into hierarchy.