We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74’s republishing terms.

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74’s republishing terms.

Sitting in his wheelchair at a highly specialized private school in Manhattan designed for students with severe and multiple disabilities, Joshua Omoloju, 17, uses assistive technology to activate his Spotify playlist, sharing snippets of his favorite songs in class — tracks even his parents were unaware he loved.

It’s a role this deejay is thrilled to fill at a school that encourages him to express himself any way he can. The magnetic and jovial Omoloju, a student at The International Academy of Hope, is legally blind, hearing impaired and nonverbal. But none of that stopped him from playing Peanut Butter Jelly Time by Buckwheat Boyz mid-lesson on a recent morning.

“OK, Josh!” his teachers said, swiveling their hips and smiling. “Let’s go!”

iHOPE, as it’s known, was established in Harlem in 2013 for just six children and moved to its current location blocks from Rockefeller Center in 2022. It now serves 150 students ages 5 through 21 and is currently at capacity with 27 people on its waitlist, according to its principal.

The four-story, nonprofit school offers age-appropriate academics alongside physical, occupational and speech therapy in addition to vision and hearing services. Every student at iHOPE has a full-time paraprofessional, who works with them throughout the day, and at least half participate in aquatic therapy in a heated cellar pool.

The school has three gymnasiums fitted with equipment to increase students’ mobility, helping many walk or stand, something they rarely do because of their physical limitations.

Its 300-member staff includes four full-time nurses and its six-figure cost averages $200,000 annually depending on each child’s needs. Parents can seek tuition reimbursement from the New York City Department of Education through legal processes set out by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, arguing that the public school cannot adequately meet their child’s needs.

iHOPE focused primarily on rehabilitation in its early years but is now centered on academics and assistive technology, particularly augmentative and alternative communication devices that improve students’ access to learning. Mastery means users can take greater control of their lives. Shani Chill, the school’s principal and executive director, said working at iHOPE allows her to witness this transformational magic each day.

“Every student who comes here is a gift that is locked away inside and the staff come together to figure that out, saying, ‘I can give you this device, this tool, these tactiles’ and suddenly the student breaks through and shows us something amazing about themselves,” she said. “You see their personality, their humor, and the true wisdom that comes from students who would otherwise be sitting there in a wheelchair with everything being done for them — or to them.”

Some devices, like the one Omoloju uses in his impromptu deejay booth, track students’ pupils, allowing them to answer questions and express, for example, joy or discomfort, prompting staff to make needed modifications.

Because he’s unable to speak, Omoloju’s parents, teachers and friends assess his mood through other means, including his laughter, which arrives with ease and frequency at iHOPE. It’s a welcome contrast to what came before it at a different school, when a sudden eruption of tears would prompt a call to his mother, who would rush down to the campus, often too late to glean what upset him.

“One of the things we saw when we first visited (iHOPE) was that they knew exactly how to work with him,” Terra Omoloju said earlier this week. “That was so impressive to me. I don’t feel anxious anymore about getting those calls.”

Yosef Travis, father to 8-year-old Juliette, said iHOPE embodies the idea that children with multiple disabilities and complex syndromes can grow with the right support.

Juliette has a rare genetic disorder that impacts brain development and is also visually impaired. She squeals with joy with one-on-one attention and often taps her feet in excitement, Chill said.

“Juliette has grown in leaps and bounds over the past three and a half years and the dedication and creativity of the staff played a significant role,” her father said. “When she is out sick or on school vacation, we can tell that she misses them.”

Travis said his family considered many options, both public and private, before choosing iHOPE.

“iHOPE was the only one that could provide a sound education without sacrificing the necessary supports and related services she needs for her educational journey,” he said.

iHOPE currently serves one child from Westchester but all the others are from New York City. Parents are not referred there by their local district: They learn about it from social workers, therapists, doctors or through their own research, the principal said.

Those seeking enrollment complete an intake process to ensure their child would be adequately served there. Parents typically make partial payments or deposits upfront — the amount varies depending on income — while seeking tuition reimbursement from the NYC DOE.

iHOPE does not receive state or federal funding but some organizations that aid its students saw their budgets slashed by the Trump administration, reducing the amount of support they can provide to families in the form of services and equipment.

You can have classrooms that feel like a babysitting facility with kids in wheelchairs given colored paper and crayons, which makes no sense. Or you have a place like iHOPE, which takes advantage of the age in which we are.

Shani Chill, iHope principal and executive director

Principal Chill said her school is devoted to giving children the tools they need, even if it means absorbing added costs.

“We’ll get it from somewhere,” she said, noting iHOPE can turn to partner organization YAI and to its own fundraising efforts to pay those expenses so that every child, no matter their challenges, can learn.

Omoloju’ symptoms mimic cerebral palsy and he also has scoliosis. He’s prone to viruses and other ailments, is frequently hospitalized and has undergone surgeries for his hip and back.

“He is also very charming,” his mother said. “He likes to have fun. He loves people. I feel very blessed that he is so joyous — even when he’s sick. He is very resilient. I love that about him. He teaches me so much.”

This is Omoloju’s fourth year at iHOPE. He’s in the upper school program — iHOPE does not use grade levels — which serves students ages 14 through 21.

He has made marked improvements in his mobility and communication since his enrollment. And his parents know he loves it there: Josh’s father, Wale, saw that firsthand after he dropped his son off at campus after a recent off-site appointment.

“I wish I had a video for when Keith [his son’s paraprofessional] came out of the elevator,” his father said. “[Josh] was beside himself laughing and was so excited to see him. He absolutely loves being there. I know he is in the right place and we love that.”

Principal Chill notes many of these students would not have been placed in an academic setting in decades past. Instead, she said, they would have been institutionalized, a cruel loss for them, their families and the greater community.

“These kids deserve an education and what that looks like runs the spectrum,” she said. “You can have classrooms that feel like a babysitting facility with kids in wheelchairs given colored paper and crayons, which makes no sense. Or you have a place like iHOPE, which takes advantage of the age in which we are.”

Chill notes that assistive and communication-related devices have improved dramatically in recent years and are only expected to develop further. She’s not sure how AI might transform their lives moving forward, but highly sensitive devices that can be operated with a glance or a light touch could be life changing, for example, allowing students to activate smart devices in their own living space.

“This is a great time when you look at all of the technology that is available,” she said.

Miriam Franco was thrilled about the progress her son, Kevin Carmona, 16, made in just his first six months at iHOPE, she said.

Kevin, a high-energy student who thrives on praise from his teachers, is also good at listening: Ever curious, he’ll keep pace with a conversation from across the room if it interests him.

Kevin has cerebral palsy and a rare genetic disorder that affects the brain and immune system. He has seizures, hip dysplasia and is fed with a gastronomy tube.

“He was able to receive a communication device, which opened an entirely new world for him and allowed him to express himself in ways he could not before,” his mother said. “He also became more engaged and independent during his physical therapy and occupational therapy sessions. His attention and focus improved when completing tasks or responding to prompts, leading to greater engagement and participation.”

His enthusiasm for the school shows itself each morning, Franco said.

“You can see how happy he is while waiting for the bus and greeting his travel paraprofessional,” she said. “It starts from the moment he wakes up and continues as he gets ready for school. In every part of his current educational setting, Kevin is given real opportunities to participate, with the support in place to make that possible.”

Principal Chill said she cherishes the moment parents visit the site for the first time, imagining all their child is capable of achieving.

“They are moved to tears, saying, ‘Now I can picture what my child can do someday,” she said.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how

Key points:

America’s special education system is facing a slow-motion collapse. Nearly 8 million students now receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), but the number of qualified teachers and related service providers continues to shrink. Districts from California to Maine report the same story: unfilled positions, overworked staff, and students missing the services they’re legally entitled to receive.

“The promise of IDEA means little if there’s no one left to deliver it.”

The data tell a clear story. Since 2013, the number of children ages 3–21 served under IDEA has grown from 6.4 million to roughly 7.5 million. Yet the teacher pipeline has moved in the opposite direction. According to Title II reports, teacher-preparation enrollments dropped 6 percent over the last decade and program completions plunged 27 percent. At the same time, nearly half of special educators leave the field within their first five years.

By 2023, 45 percent of public schools were operating without a full teaching staff. Vacancies were most acute in special education. Attrition, burnout, and early retirements outpace new entrants by a wide margin.

Why the traditional model no longer works

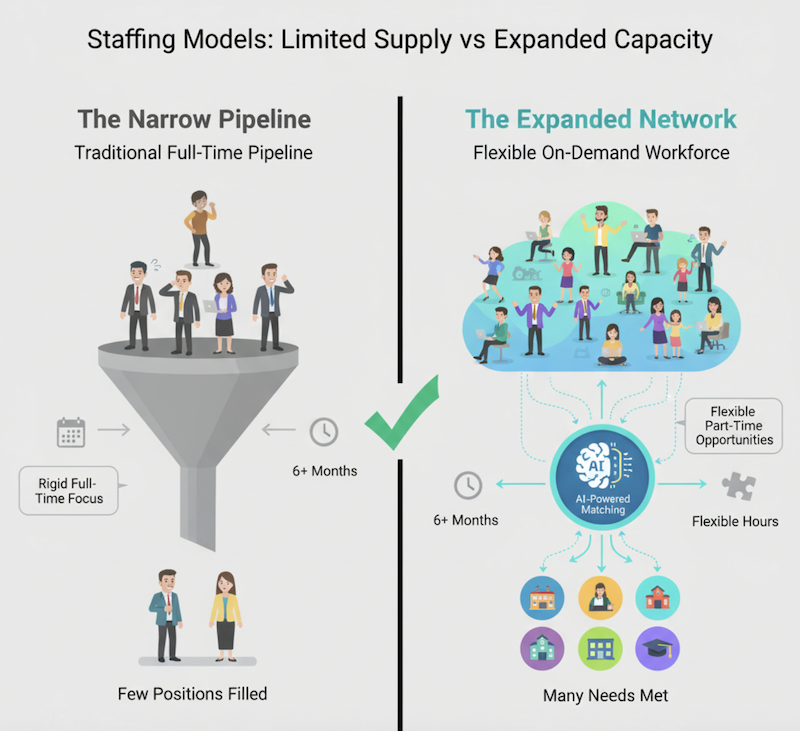

For decades, schools and staffing firms have fought over the same dwindling pool of licensed providers. Recruiting cycles stretch for months, while students wait for evaluations, therapies, or IEP services.

Traditional staffing firms focus on long-term contracts lasting six months or more, which makes sense for stability, but ignores an enormous, untapped workforce: thousands of credentialed professionals who could contribute a few extra hours each week if the system made it easy.

Meanwhile, the process of credentialing, vetting, and matching candidates remains slow and manual, reliant on spreadsheets, email, and recruiters juggling dozens of openings. The result is predictable: delayed assessments, compliance risk, and burned-out staff covering for unfilled roles.

“Districts and recruiters compete for the same people, when they could be expanding the pool instead.”

The hidden workforce hiding in plain sight

Across the country, tens of thousands of licensed professionals–speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, school psychologists, special educators–are under-employed. Many have stepped back from full-time work to care for families or pursue private practice. Others left the classroom but still want to contribute.

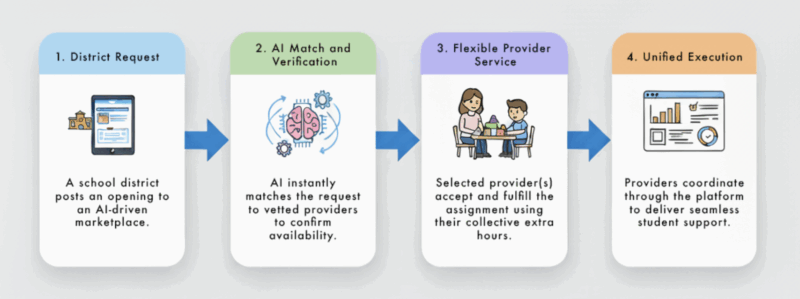

Imagine if districts could tap those “extra hours” through a vetted, AI-powered marketplace. A system that matched real-time school requests with qualified providers in their state. A model like this wouldn’t replace full-time roles; it would expand capacity, reduce burnout, and bring talent back into the system.

This isn’t theoretical. The same “on-demand” concept has already modernized industries from medicine to media. Education is long overdue for the same reinvention.

What modernization looks like

A moment of urgency

The shortage isn’t just inconvenient; it’s systemic. Each unfilled position represents students who lose therapy hours, districts risking due-process complaints, and educators pushed closer to burnout.

With IDEA students now representing nearly 15 percent of all public school enrollment, the nation can’t afford to let a twentieth-century staffing model dictate twenty-first-century outcomes.

We have the technology. We have the workforce. What we need is the will to connect them.

“Modernizing special education staffing isn’t innovation for innovation’s sake, it’s survival.”

Key points:

When I first started experimenting with AI in my classroom, I saw the same thing repeatedly from students. They treated it like Google. Ask a question, get an answer, move on. It didn’t take long to realize that if my students only engage with AI this way, they miss the bigger opportunity to use AI as a partner in thinking. AI isn’t a magic answer machine. It’s a tool for creativity and problem-solving. The challenge for us as educators is to rethink how we prepare students for the world they’re entering and to use AI with curiosity and fidelity.

Moving from curiosity to fluency

In my district, I wear two hats: history teacher and instructional coach. That combination gives me the space to test ideas in the classroom and support colleagues as they try new tools. What I’ve learned is that AI fluency requires far more than knowing how to log into a platform. Students need to learn how to question outputs, verify information and use results as a springboard for deeper inquiry.

I often remind them, “You never trust your source. You always verify and compare.” If students accept every AI response at face value, they’re not building the critical habits they’ll need in college or in the workforce.

To make this concrete, I teach my students the RISEN framework: Role, Instructions, Steps, Examples, Narrowing. It helps them craft better prompts and think about the kind of response they want. Instead of typing “explain photosynthesis,” they might ask, “Act as a biologist explaining photosynthesis to a tenth grader. Use three steps with an analogy, then provide a short quiz at the end.” Suddenly, the interaction becomes purposeful, structured and reflective of real learning.

AI as a catalyst for equity and personalization

Growing up, I was lucky. My mom was college educated and sat with me to go over almost every paper I wrote. She gave me feedback that helped to sharpen my writing and build my confidence. Many of my students don’t have that luxury. For these learners, AI can be the academic coach they might not otherwise have.

That doesn’t mean AI replaces human connection. Nothing can. But it can provide feedback, ask guiding questions, and provide examples that give students a sounding board and thought partner. It’s one more way to move closer to providing personalized support for learners based on need.

Of course, equity cuts both ways. If only some students have access to AI or if we use it without considering its bias, we risk widening the very gaps we hope to close. That’s why it’s our job as educators to model ethical and critical use, not just the mechanics.

Shifting how we assess learning

One of the biggest shifts I’ve made is rethinking how I assess students. If I only grade the final product, I’m essentially inviting them to use AI as a shortcut. Instead, I focus on the process: How did they engage with the tool? How did they verify and cross-reference results? How did they revise their work based on what they learned? What framework guided their inquiry? In this way, AI becomes part of their learning journey rather than just an endpoint.

I’ve asked students to run the same question through multiple AI platforms and then compare the outputs. What were the differences? Which response feels most accurate or useful? What assumptions might be at play? These conversations push students to defend their thinking and use AI critically, not passively.

Navigating privacy and policy

Another responsibility we carry as educators is protecting our students. Data privacy is a serious concern. In my school, we use a “walled garden” version of AI so that student data doesn’t get used for training. Even with those safeguards in place, I remind colleagues never to enter identifiable student information into a tool.

Policies will continue to evolve, but for day-to-day activities and planning, teachers need to model caution and responsibility. Students are taking our lead.

Professional growth for a changing profession

The truth of the matter is most of us have not been professionally trained to do this. My teacher preparation program certainly did not include modules on prompt engineering or data ethics. That means professional development in this space is a must.

I’ve grown the most in my AI fluency by working alongside other educators who are experimenting, sharing stories, and comparing notes. AI is moving fast. No one has all the answers. But we can build confidence together by trying, reflecting, and adjusting through shared experience and lessons learned. That’s exactly what we’re doing in the Lead for Learners network. It’s a space where educators from across the country connect, learn and support one another in navigating change.

For educators who feel hesitant, I’d say this: You don’t need to be an expert to start. Pick one tool, test it in one lesson, and talk openly with your students about what you’re learning. They’ll respect your honesty and join you in the process.

Preparing students for what’s next

AI is not going away. Whether we’re ready or not, it’s going to shape how our students live and work. That gives us a responsibility not just to keep pace with technology but to prepare young people for what’s ahead. The latest futures forecast reminds us that imagining possibilities is just as important as responding to immediate shifts.

We need to understand both how AI is already reshaping education delivery and how new waves of change will remain on the horizon as tools grow more sophisticated and widespread.

I want my students to leave my classroom with the ability to question, create, and collaborate using AI. I want them to see it not as a shortcut but as a tool for thinking more deeply and expressing themselves more fully. And I want them to watch me modeling those same habits: curiosity, caution, creativity, and ethical decision-making. Because if we don’t show them what responsible use looks like, who will?

The future of education won’t be defined by whether we allow AI into our classrooms. It will be defined by how we teach with it, how we teach about it, and how we prepare our students to thrive in a world where it’s everywhere.

Key points:

Districts nationwide are grappling with increased special education demands amid persistent staff shortages and compliance pressures. At the intersection of technology and student support, Maura Connor, chief operating officer of Better Speech, is leading the launch of Streamline, an AI-powered special education management platform designed to ease administrative burdens and enhance service delivery.

In this Q&A, Connor discusses the realistic, responsible ways AI can empower educators, optimize workflows, and foster stronger connections between schools and families.

1. Many districts are experiencing an increase in special education caseloads while struggling with staff shortages and retention. From your perspective, where can AI most realistically help relieve pressure on special educators without compromising their quality of service?

AI is most impactful when it handles time-intensive, repetitive tasks that don’t require nuanced human judgment. For example, AI can assist in drafting initial progress or intervention notes and tracking intervention outcomes to help identify students who may need additional support. By automating these administrative tasks, special educators and service providers can spend more time delivering direct instruction or therapy, collaborating with colleagues, and planning individualized support for students.

Importantly, AI is a tool that augments, not replaces, human expertise. It can relieve pressure in the special education ecosystem while allowing educators to maintain the high-quality services students need.

2. Special education leaders need to balance efficiency with compliance when it comes to IEP evaluations and goals. How can AI help schools and districts with this?

AI can standardize data collection and analysis, ensuring evaluations capture all legally required components while reducing the manual burden. Advanced AI analytics can also flag potential compliance gaps before they become serious risks and help identify patterns across a student’s performance.

For case managers and providers, especially those new to special education, AI can accelerate skill-building by helping draft legally-defensible, evidence-based IEP goals and recommendations. Rather than spending hours on formatting and documentation, this allows educators and administrators to focus on meaningful decision-making, personalized student support, and family engagement.

3. Beyond easing paperwork, what are some practical ways school and district leaders can use AI to reallocate staff time toward more student-facing work?

AI can help leaders identify trends and bottlenecks across their special education programs, such as caseload imbalances, scheduling inefficiencies, budget planning, or capacity in high-demand intervention areas. By surfacing these insights, districts can make data-informed staffing adjustments, prioritize coaching and professional development, and streamline workflows so teachers and service providers are freed up for individual instruction, small-group interventions, and collaborative planning.

Essentially, AI can turn administrative time into actionable intelligence that translates directly into better targeted student support.

4. When it comes to parent engagement, how can AI support stronger, more transparent communication between schools and families?

Parent engagement in the special education process can be a sensitive experience for districts and families alike. And, it’s a critical challenge we often hear about from leaders and teachers.

AI relieves some of the pressure by generating clear, real-time updates on student progress. In this way, AI can increase transparency and communication, helping families stay informed and engaged without overwhelming staff through repetitive outreach. For example, automated notifications about milestones, progress toward IEP goals, or upcoming meetings can ensure families receive timely, understandable information.

AI can also assist in translating materials for non-English-speaking families, creating more equitable access to information and empowering parents to be active partners in their child’s education.

5. Given the growing availability and use of generative AI tools, how can school and district leaders set guardrails to ensure educators use these tools ethically and securely?

Responsible and ethical use of AI in education starts with districts setting clear policies and engaging in targeted professional development. Leaders should define boundaries around student data privacy, clarify when AI outputs require human review, and provide training on responsible AI use. AI should always enhance staff capacity without compromising student safety or the integrity of decision-making. Since AI can “hallucinate,” it is absolutely critical that educators and providers use their own professional and clinical judgment in reviewing and approving any recommendations generated by AI. Districts should also consider using a proprietary, evidence-based LLM engine instead of open-source AI tools to lessen this risk.

Establishing guardrails also means monitoring usage, maintaining transparency with families, and fostering a culture where AI is a support, not a replacement, for professional and clinical judgment.

6. Overall, what role can AI-powered analytics play in helping school and district leaders make more data-driven, proactive decisions?

AI-powered analytics can transform reactive management into proactive planning. By aggregating and analyzing multiple data points–from academic performance to intervention outcomes–leaders can identify trends and potential compliance issues before they become legal risks. District leaders can also allocate resources more strategically and design targeted programs for students who need the most support or readily plan for coverage or extra resources when settings need to increase capacity.

Overall, AI’s predictive capability can help districts move beyond compliance toward strategic continuous improvement, ensuring every decision is informed by actionable insights rather than intuition alone.

Maura Connor is Chief Operating Officer of Better Speech, where she leads the launch of Streamline, an AI-powered special education management platform that reduces administrative burden and empowers schools to better support students and families. With extensive leadership experience across education and healthcare technology, she specializes in scaling organizations, driving innovation, and advancing solutions that improve outcomes for children and communities.

Two months after Education Secretary Linda McMahon was confirmed, she and a small team from the department met with leadership from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, an advocacy group that works on behalf of millions of students with dyslexia and other disorders.

Jacqueline Rodriguez, NCLD’s chief executive officer, recalled pressing McMahon on a question raised during her confirmation hearing: Was the Trump administration planning to move control and oversight of special education law from the Education Department to Health and Human Services?

Rodriguez was alarmed at the prospect of uprooting the 50-year-old Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA), which spells out the responsibility of schools to provide a “free, appropriate public education” to students with disabilities. Eliminating the Education Department entirely is a primary objective of Project 2025, the conservative blueprint that has guided much of the administration’s education policy. After the department is gone, Project 2025 said oversight of special education should move to HHS, which manages some programs that help adults with disabilities.

But the sprawling department that oversees public health has no expertise in the complex education law, Rodriguez told McMahon.

“Someone might be able to push the button to disseminate funding, but they wouldn’t be able to answer a question from a parent or a school district,” she said in an interview later.

For her part, McMahon had wavered during her confirmation hearing on the subject. “I’m not sure that it’s not better served in HHS, but I don’t know,” she told Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., who shared concerns from parents worried about who would enforce the law’s provisions.

But nine days into a government shutdown that has furloughed most federal government workers, the Trump administration announced that it was planning a drastic “reduction in force” that would lay off more than 450 people, including almost everyone who works in the Office of Special Education Programs. Rodriguez believes the layoffs are a way that the administration plans to force the special education law to be managed by some other federal office.

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

The Education Department press office did not respond to a question about the administration’s plans for special education oversight. Instead, the press office pointed to a social media post from McMahon on Oct. 15. The fact that schools are “operating as normal” during the government shutdown, McMahon wrote on X, “confirms what the President has said: the federal Department of Education is unnecessary.”’

Yet in that May meeting, Rodriguez said she was told that HHS might not be the right place for IDEA, she recalled. While the new department leadership made no promises, they assured her that any move of the law’s oversight would have to be done with congressional approval, Rodriguez said she was told.

The move to gut the office overseeing special education law was shocking to families and those who work with students with disabilities. About 7.5 million children ages 3 to 21 are served under IDEA, and the office had already lost staffers after the Trump administration dismissed nearly half the Education Department’s staff in March, bringing the agency’s total workforce to around 2,200 people.

For Rodriguez, whose organization supports students with learning disabilities such as dyslexia, McMahon’s private assurances was the administration “just outright lying to the public about their intentions.”

“The audacity of this administration to communicate in her confirmation, in her recent testimony to Congress and to a disability rights leader to her face, ‘Don’t worry, we will support kids with disabilities,’” Rodriguez said. “And then to not just turn a 180-degree on that, but to decimate the ability to enforce the law that supports our kids.”

She added: “It could not just be contradictory. It feels like a bait and switch.”

Five days after the firings were announced, a U.S. district judge temporarily blocked the administration’s actions, setting up a legal showdown that is likely to end up before the Supreme Court. The high court has sided with the president on most of his efforts to drastically reshape the federal workforce. And President Donald Trump said at a Tuesday press briefing that more cuts to “Democrat programs” are coming.

“They’re never going to come back in many cases,” he added.

Related: Hundreds of thousands of students are entitled to training and help finding jobs. They don’t get it

In her post on X, McMahon also said that “no education funding is impacted by the RIF, including funding for special education,” referring to the layoffs.

But special education is more than just money, said Danielle Kovach, a special education teacher in Hopatcong, N.J. Kovach is also a former president of the Council for Exceptional Children, a national organization for special educators.

“I equate it to, what would happen if we dismantled a control tower at a busy airport?” Kovach said. “It doesn’t fly the plane. It doesn’t tell people where to go. But it ensures that everyone flies smoothly.”

Katy Neas, a deputy assistant secretary in the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services during the Biden administration, said that most people involved in the education system want to do right by children.

“You can’t do right if you don’t know what the answer is,” said Neas, who is now the chief executive officer of The Arc of the United States, which advocates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. “You can’t get there if you don’t know how to get your questions answered.”

Families also rely on IDEA’s mandate that each child with a disability receives a free, appropriate public education — and the protections that they can receive if a school or district does not live up to that requirement.

Maribel Gardea, a parent in San Antonio, said she fought with her son’s school district for years over accommodations for his disability. Her son Voozeki, 14, has cerebral palsy and is nonverbal. He uses an eye-gaze device that allows him to communicate when he looks at different symbols on a portable screen. The district resisted getting the device for him to use at school until, Gardea said, she reminded them of IDEA’s requirements.

“That really stood them up,” she said.

Related: Trump wants to shake up education. What that could mean for a charter school started by a GOP senator’s wife

Gardea, the co-founder of MindShiftED, an organization that helps parents become better advocates for their children with disabilities, said the upheaval at the Education Department has her wondering what kind of advice she can give families now.

For example, an upcoming group session will teach parents how to file official grievances to the federal government if they have disputes with their child’s school or district about services. Now, she has to add in an explanation of what the deep federal cuts will mean for parents.

“I have to tell you how to do a grievance,” she said she plans to tell parents. “But I have to tell you no one will answer.”

Maybe grassroots organizations may find themselves trying to track parent complaints on their own, she said, but the prospect is exhausting. “It’s a really gross feeling to know that no one has my back.”

In addition to the office that oversees special education law, the Rehabilitation Services Administration, which is also housed at the Department of Education and supports employment and training of people with disabilities, was told most of its staff would be fired.

“Regardless of which office you’re worried about, this is all very intentional,” said Julie Christensen, the executive director of the Association of People Supporting Employment First, which advocates for the full inclusion of people with disabilities in the workforce. “There’s no one who can officially answer questions. It feels like that was kind of the intent, to just create a lot of confusion and chaos.”

Those staffers “are the voice within the federal government to make sure policies and funding are aligned to help people with disabilities get into work,” Christensen said. Firing them, she added, is counterintuitive to everything the administration says it cares about.

For now, advocates say they are bracing for a battle similar to those fought decades ago that led to the enactment of civil rights law protecting children and adults with disabilities. Before the law was passed, there was no federal guarantee that a student with a disability would be allowed to attend public school.

“We need to put together our collective voices. It was our collective voices that got us here,” Kovach said.

And, Rodriguez said, parents of children in special education need to be prepared to be their own watchdogs. “You have to become the compliance monitor.”

It’s unfair, she said, but necessary.

Contact staff writer Christina Samuels at 212-678-3635 or [email protected].

This story about special education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.