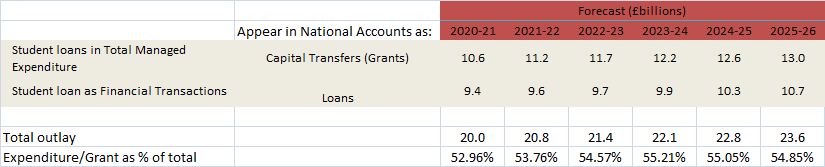

With the Comprehensive Spending Review due next Wednesday, I thought it might be worth making some general points about student loans (in anticipation of potential changes to repayment thresholds and other parameters).

I do not think student loans are a good vehicle for redistributive measures.

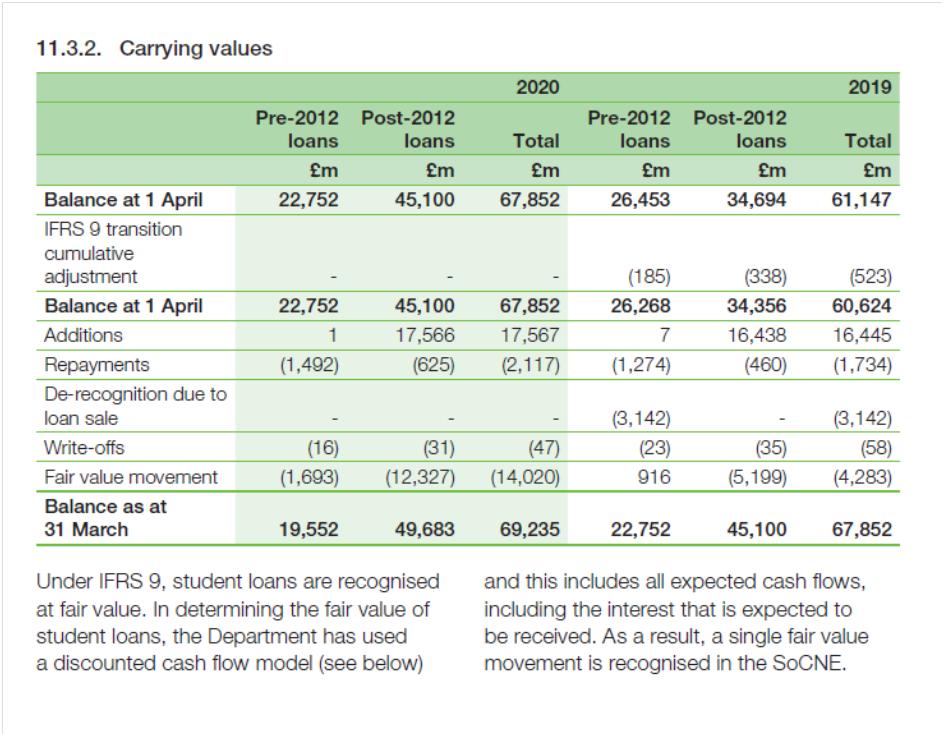

As I told a couple of parliamentary committees in 2017, the current redistributive aspects are an accidental function of the decision to lower the financial reporting discount rate for student loans from RPI plus 2.2 percent to RPI plus 0.7. Such a downwards revision elevates the value of future cash repayments and in this case it meant that the payments projected to be received from higher earners began to exceed the value of the initial cash outlay.

The caveat here: in the eyes of government. That is the government’s discount rate, not necessarily yours. One of the reasons I favour zero real interest rates over other options is that it simplifies considerations of the future value of payments made from the individual borrower’s perspective.

Originally, student loans were proposed as a way to eliminate a middle class subsidy – free tuition – and have now become embedded as a way to fund mass, but not universal, provision.

I believe that if you are concerned about redistribution, then it is best to concentrate on the broader tax system, rather than focusing solely on the progressivity or otherwise of student loans. You can see from the original designs for the 2012 changes that the idea of the higher interest rates were meant to make the loan scheme mimic a proportionate graduate tax and eliminate the interest rate subsidy enjoyed by higher earners on older loans. The original choice of “post-2012” student loan interest rates of RPI + 0 to 3 percentage points was meant to match roughly the old discount rate of RPI plus 2.2%. Again, see my submission to the Treasury select committee for more detail.

I will just set out a few illustrative examples here as to why some of the debates about fairness in relation to repayment terms need a broader lens.

It is often observed that two graduates on the same salaries are left with different disposable incomes, if one has benefited from their parents, say, paying their tuition fees and costs of living during study so that they don’t lose 9 per cent of their salary over the repayment threshold (just under £20,000 per year for pre-2012 loans; just over £27,000 for post-2012 loans).

That’s clearly the case.

But the parents had to pay c. £50,000 upfront to gain that benefit for their child. And it is by no means certain that option is the best use of such available money. Only a minority of borrowers go on to repay the equivalent of what they borrowed using the government’s discount rate, and as an individual you should probably have a higher discount rate than the government. You also forego the built-in death and disability insurance in student loans.

Payment upfront is therefore a gamble, one where the odds differ markedly for men and women. (See analyses by London Economics and Institute for Fiscal Affairs for the breakdowns on the different percentages of men and women who do pay the equivalent of more than they borrowed.)

If a family has the £50,000 spare (certainly don’t borrow it from elsewhere), then the following options are likely more sensible:

- pledge to cover your child’s rent until the £50,000 runs out: this allows student to avoid taking on excessive paid work during study and will boost their disposable income afterwards;

- provide the £50,000 as a deposit towards a house purchase;

- even put the £50,000 in a pot to cover the student loan repayments as they arise;

- etc.

In two of those cases, you’ll have a useful contingency fund too.

All strike me as better options than eschewing the government-subsidised loan scheme.

Moreover, those three options remain in the event of a graduate tax or the abolition of tuition fees.

That fundamental unfairness – family wealth – isn’t addressed by changing the HE funding system. (I write as someone who helped craft the HE pledges in Labour’s 2015 and 2017 manifestos).

In many ways, the government prefers people to pay upfront because it reduces the immediate cash demand. From that perspective, upfront payment works as a form of voluntary wealth taxation (at least in the short-run). Arguably, those who pay upfront have been taxed at the beginning and are gambling on outcomes that mean that future “rebates” exceed the original payment for their children.

Perhaps this line of reasoning opens up debates about means-testing fees and emphasises the need to restore maintenance grants … but really it points to harder problems regarding the taxation of intergenerational transfers and disposable wealth.

I am not a certified financial advisor so comments above are simply my opinions. You should not base investment decisions on them.