The federal student loan portfolio, totaling roughly $1.6 to $1.7 trillion, is not merely an accounting entry. It is one of the largest consumer credit systems in the world and functions simultaneously as a public policy tool, a long-term revenue stream, a data infrastructure, and a political liability. It shapes who can access higher education, how risk is distributed across generations, and how the federal government exerts leverage over the postsecondary sector. Precisely because of its scale and visibility, the portfolio is uniquely vulnerable to narrative reframing.

That vulnerability was not accidental. It was constructed over decades through a series of policy decisions that stripped borrowers of normal consumer protections while preserving the financial attractiveness of student debt as an asset. Chief among these decisions was the gradual removal of bankruptcy protections for student loans. By rendering student debt effectively nondischargeable except under the narrow and punitive “undue hardship” standard, lawmakers transformed education loans into a uniquely durable financial instrument. Unlike mortgages, credit cards, or medical debt, student loans could follow borrowers for life, enforced through wage garnishment, tax refund seizure, and Social Security offsets.

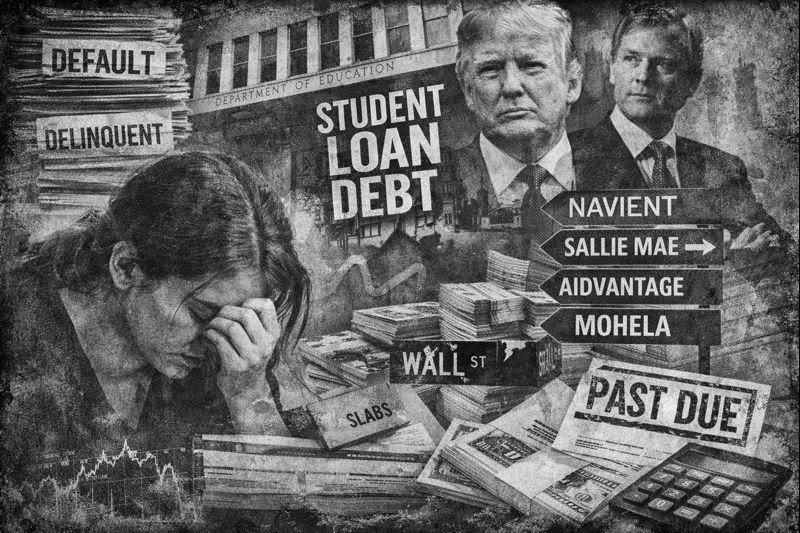

This transformation made student loans exceptionally attractive for securitization. Student Loan Asset-Backed Securities, or SLABS, flourished precisely because the underlying loans were shielded from traditional credit risk. Investors could rely not on educational outcomes or borrower prosperity, but on the legal certainty that the debt would remain collectible. Even during economic downturns, SLABS were marketed as relatively stable instruments, insulated from the discharge risks that plagued other forms of consumer credit.

Private banks once dominated this market. Sallie Mae, originally a government-sponsored enterprise, became a central player in both originating and securitizing student loans, while Navient emerged as a major servicer and asset manager. Yet as Higher Education Inquirer documented in early 2025, banks ultimately lost control of student lending. Rising defaults, public outrage, state enforcement actions, and mounting evidence of predatory practices made the sector politically radioactive. The federal government stepped in not as a reformer, but as a backstop, absorbing the portfolio and stabilizing a system private finance could no longer manage without reputational and regulatory risk.

That history reveals a recurring pattern. When student lending fails in private hands, it becomes public. When the public system is allowed to fail, it becomes ripe for re-privatization.

A portfolio does not need to collapse to be declared unmanageable. It only needs to appear dysfunctional enough to justify extraordinary intervention.

The post-pandemic repayment restart, persistent servicing failures, legal challenges to income-driven repayment plans, and widespread borrower confusion have all contributed to a growing narrative of systemic breakdown. Servicers such as Maximus, operating under the Aidvantage brand, MOHELA, and others have struggled to process payments accurately, manage forgiveness programs, and provide reliable customer service. These failures are often framed as bureaucratic incompetence rather than as predictable consequences of outsourcing public functions to private contractors whose incentives are misaligned with borrower welfare.

Navient’s exit from federal servicing did not mark a retreat from the student loan ecosystem so much as a repositioning, as it continued to benefit from private loan portfolios and legacy SLABS exposure. Sallie Mae, rebranded and fully privatized, remains deeply embedded in the private student loan market, which continues to rely on the same nondischargeability framework that props up federal lending.

Crucially, these servicing failures cannot be separated from the earlier elimination of bankruptcy as a safety valve. In normal credit markets, distress is resolved through restructuring or discharge. In student lending, distress accumulates. Borrowers remain trapped, servicers remain paid, and policymakers are confronted with a swelling mass of unresolved debt that can be labeled a crisis at any politically convenient moment.

Under pyrrhic defeat theory, such a crisis is not merely tolerated. It is useful.

Once the federal portfolio is framed as broken beyond repair, the range of acceptable solutions expands. What would be politically impossible in a stable system becomes plausible in an emergency. Asset transfers, securitization of federal loans, expansion of SLABS-like instruments backed by government guarantees, or long-term conveyance of servicing and collection rights can be presented as pragmatic fixes rather than ideological choices.

A Trump administration would be particularly well positioned to exploit this dynamic. Skeptical of debt relief, hostile to administrative governance, and ideologically aligned with privatization, such an administration could recast the portfolio as a failed public experiment inherited from predecessors. In that framing, selling or offloading the portfolio is not an abdication of responsibility but an act of fiscal discipline.

Importantly, this need not take the form of an explicit, congressionally authorized sale. Risk can be shifted through securitization. Revenue streams can be monetized. Servicing authority can be extended indefinitely to private firms. Data control can migrate outside public oversight. Over time, these steps amount to de facto privatization, even if the loans remain nominally federal. The infrastructure, incentives, and profits move outward, while the political blame remains with the state.

This is where earlier McKinsey & Company studies reenter the conversation. Long before the current turmoil, McKinsey analyses identified high servicing costs, fragmented contractor oversight, weak borrower segmentation, and low political returns on administrative complexity. While framed as efficiency critiques, these studies implicitly favored market-oriented restructuring. In a crisis environment, such recommendations become blueprints for divestment.

The danger of a pyrrhic defeat strategy is that it delivers a short-term political win at the cost of long-term public capacity. Selling or functionally privatizing the student loan portfolio may improve fiscal optics, but it permanently weakens democratic control over higher education finance. Borrowers, already stripped of bankruptcy protections, lose what remains of public accountability. Policymakers lose leverage over tuition inflation and institutional behavior. The federal government relinquishes a powerful counter-cyclical tool. What remains is a debt regime optimized for extraction, enforced by servicers, securitized for investors, and detached from educational outcomes.

The defeat is real. It is borne by students, families, and future generations. The victory belongs to those who acquire distressed public assets and those who benefit ideologically from shrinking the public sphere.

Pyrrhic defeat theory reminds us that collapse is not always accidental. In the case of the federal student loan portfolio, what appears to be dysfunction or incompetence may instead be strategic surrender: a willingness to let a public system deteriorate so that it can be sold off, securitized, or outsourced under the banner of necessity. If that happens, it will not be remembered as a policy error, but as a deliberate transfer of public wealth and power—made possible by decades of legal engineering that began when bankruptcy protection was taken away and ended with student debt transformed into a permanent financial asset.

Sources

Higher Education Inquirer. “When Banks Lost Control of Student Loan Lending.” January 2025.

https://www.highereducationinquirer.org/2025/01/when-banks-lost-control-of-student-loan.html

U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid. FY 2024 Annual Agency Performance Report. January 13, 2025.

U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid. Federal Student Loan Portfolio Data and Statistics, various years.

Government Accountability Office. Student Loans: Key Weaknesses in Servicing and Oversight, multiple reports.

Congressional Budget Office. The Federal Student Loan Portfolio: Budgetary Costs and Policy Options.

U.S. Congress. Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 and prior amendments affecting student loan dischargeability.

Pardo, Rafael I., and Michelle R. Lacey. “The Real Student-Loan Scandal: Undue Hardship Discharge Litigation.” American Bankruptcy Law Journal.

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission materials on asset-backed securities and consumer credit markets.

McKinsey & Company. Student Loan Servicing, Portfolio Optimization, and Risk Management Analyses, prepared for federal agencies and financial institutions, 2010s–early 2020s.

Higher Education Inquirer archives on SLABS, servicers, privatization, deregulation, and student loan policy.