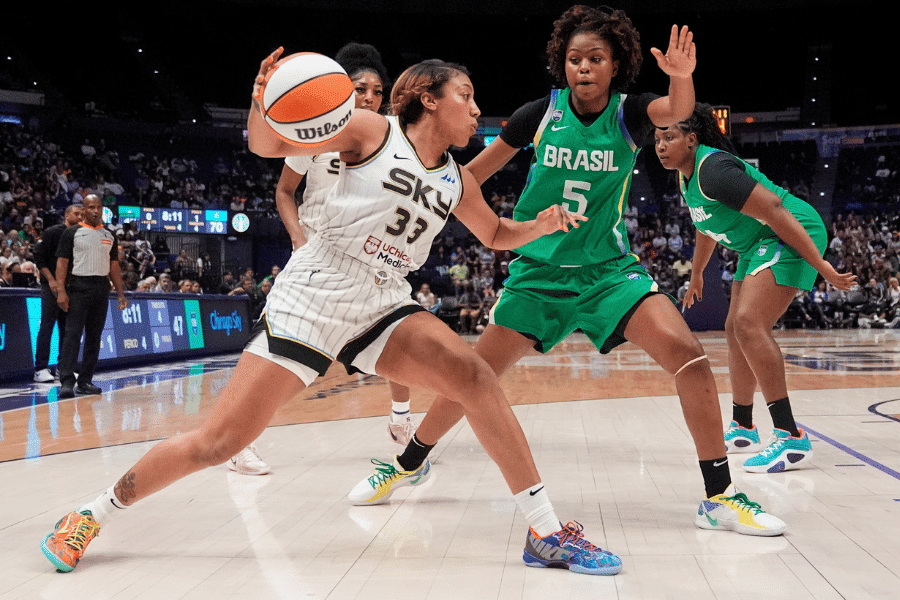

Last year was arguably the best year for women’s sports yet.

According to data analysis company S&P Global, in-person attendance and viewership were higher, with women’s professional sports sponsorships increasing by 22% since 2023. According to UN Women Australia, globally, there has been a lack of interest in women’s sports. But it seems that they might finally be getting the attention they deserve.

To find out what is driving this change in attitude towards women’s sports, I interviewed 10 women athletes across high school, university, and coaching.

Historically, women’s sports have not gotten the recognition that they deserve. However, during 2024, women’s collegiate basketball had a significant increase in viewership compared to the previous year. The Final Four game in 2024 was a showdown between two players from two U.S. universities: Caitlin Clark of the University of Iowa and Paige Bueckers of the University of Connecticut. The game drew in a peak audience of 16.1 million, according to an article in Sports Illustrated.

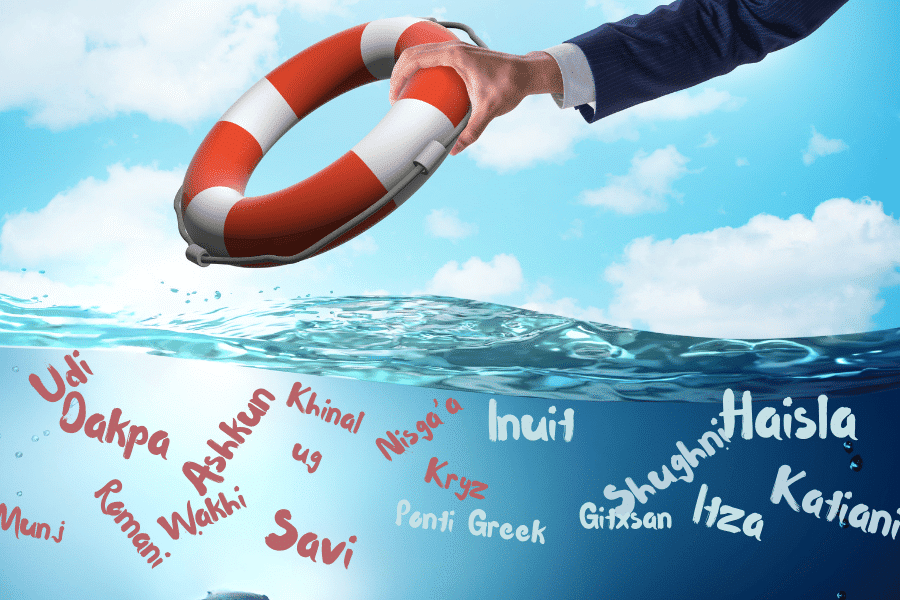

Women’s media coverage has tripled since 2019. At this rate, if coverage trends continue, women’s share of coverage could reach 20% by the end of this year, according to Women.org, an organization within the United Nations devoted to gender equality and the empowerment of women.

Gender parity in sports

The Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games were officially the first to see 50:50 coverage in gender equality.

Avery Elliot, a track and field athlete from the University of Pennsylvania, attended the Paris Olympics as a spectator and said she noticed the change – more social media presence and sponsorships, particularly highlighting women of color, especially in women’s gymnastics, spurred by the popularity and success of U.S. athletes Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles and Brazilian Rebeca Andrade.

The lack of media coverage of women has always played a role in the lack of recognition that they receive. Lanae Carrington, a track star at Lehigh University in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, said that in the past, women athletes would get dismissed for getting a low number of views or for the belief that women’s games were not as entertaining as those of men. “Overall, women are making a stronger impact in the entertainment industry, whether that’s more highlight reels on TikTok or screen time on TV,” Carrington said. “It’s finally becoming normalized.”

One of the hardest things to deal with as an athlete is a lack of support, whether from the media, in person or on the sidelines.

Brianna Gautier, a volleyball and basketball sensation at Neumann University in Pennsylvania, said it is hard to play a game where you’re not going to have a full house. “But it’s kind of helped me learn to just play for myself instead of waiting for people to show up and relying on that to bring some type of energy because I feel like it starts within you and your teammates,” she said.

Play for yourself first

As a track and field athlete, I have seen this firsthand. It is unfortunate to see people walk away after the men are finished competing. But I found that when you start showing up for yourself with energy, success comes rolling in. Gautier has embraced the idea of playing for herself and nobody else.

It used to be that at Neumann, people would attend the men’s basketball games but never stay afterward to support the women. She also expressed the importance of the support of NBA players such as Steph Curry, who came out to watch several women’s Stanford basketball games in 2023. Gautier said that people think to themselves that if their favorite male basketball players are tuning in to watch women’s sports, it must be worthwhile.

Carrington said parents also need to support their daughters in athletics. “This is important because many girls don’t have parents who encourage them to play more traditionally masculine sports, such as basketball and soccer,” she said.

Most of the women I interviewed commented on the change in the WNBA as the catalyst for the change in women’s sports..

Liz Spagnolo is a soccer player at Tower Hill High School in the U.S. state of Delaware who appreciates the opportunities she now has. “Women in sports is big for us because based on women 100 years ago, we wouldn’t be expected to play sports, or be expected to do something like cheer,” Spagnolo said.

The Caitlin Clark effect

Arianna Montgomery, an athlete at The Tatnall School, the private school in Delaware that I also attend, said she appreciates the change in women’s basketball.

“It’s gotten a lot more fame, definitely more college sports have gotten a lot more fame,” Montgomery said. “I think women’s games are starting to become more popular. People are starting to look more towards women’s sports as well as men’s sports, and even since before, instead of men’s sports now, a decade ago, that wasn’t the case.”

Many of the women I spoke to said that a big contributor to the success of women’s sports is due to the Catlin Clark effect. The Caitlin Clark effect is a term that was created after her record-breaking seasons playing women’s basketball at the University of Iowa during the years of 2023-2024.

As a result, she has become the all-time leading scorer in college basketball before entering the WNBA, and has reportedly signed sponsorship deals worth more than $11 million.

Ruth Hiller, a lacrosse coach at my school said that are a number of successful women athletes that young women can now look up to, including tennis superstars Venus and Serena Williams and Alex Morgan, the former captain of the U.S. women’s soccer team, women’s tennis pioneer Billie Jean King and Charlotte North, a professional lacrosse player who broke the all-time goals record in college lacrosse.

Women now rack up medals and points

Daija Lampkin, my track and field coach, pointed to Alison Felix, who won more medals than any other U.S. track and field athlete, and tennis superstar Serena Williams.

It is important, Lampkin said, that women support women. “Our body is critical, and some women are self-conscious that they are going to be muscular,” Lampkin said. “It can tear down your confidence. It’s not talked about in sports how women look at their bodies. People tear down Serena Williams and her body all the time, but look at where she is and how much she has accomplished”.

I have been participating in sports since I was 3 years old, when my parents signed me up for gymnastics. I run track and field and am a runner, jumper and hurdler. I began training for track and field competitions at the age of 8, and my dad has been my coach since the very beginning.

In my experience, my father was instrumental in encouraging me to participate in dance and gymnastics growing up, while also encouraging me to run track and play basketball and soccer for fun.

With opportunity comes pressure, and Gautier said it is important for girls not to put too much pressure on themselves. “When you are an athlete, you tend to feel that you have to perform a certain way to be successful or please everyone else, but I feel you kind of get blinded by the fact that you are doing it for yourself,” she said.

Questions to consider:

1. Why have women not gotten the same recognition and pay as male athletes in sports?

2. What does “parity” mean when it comes to gender in sports?

3. Should there be any differentiation when it comes to gender in sports and why?