For a few years now when touring around SUs to deliver training over the summer, me and my colleague Mack (and in previous years, Livia) have been encountering interesting tales of treatment that feel different but are hard to explain.

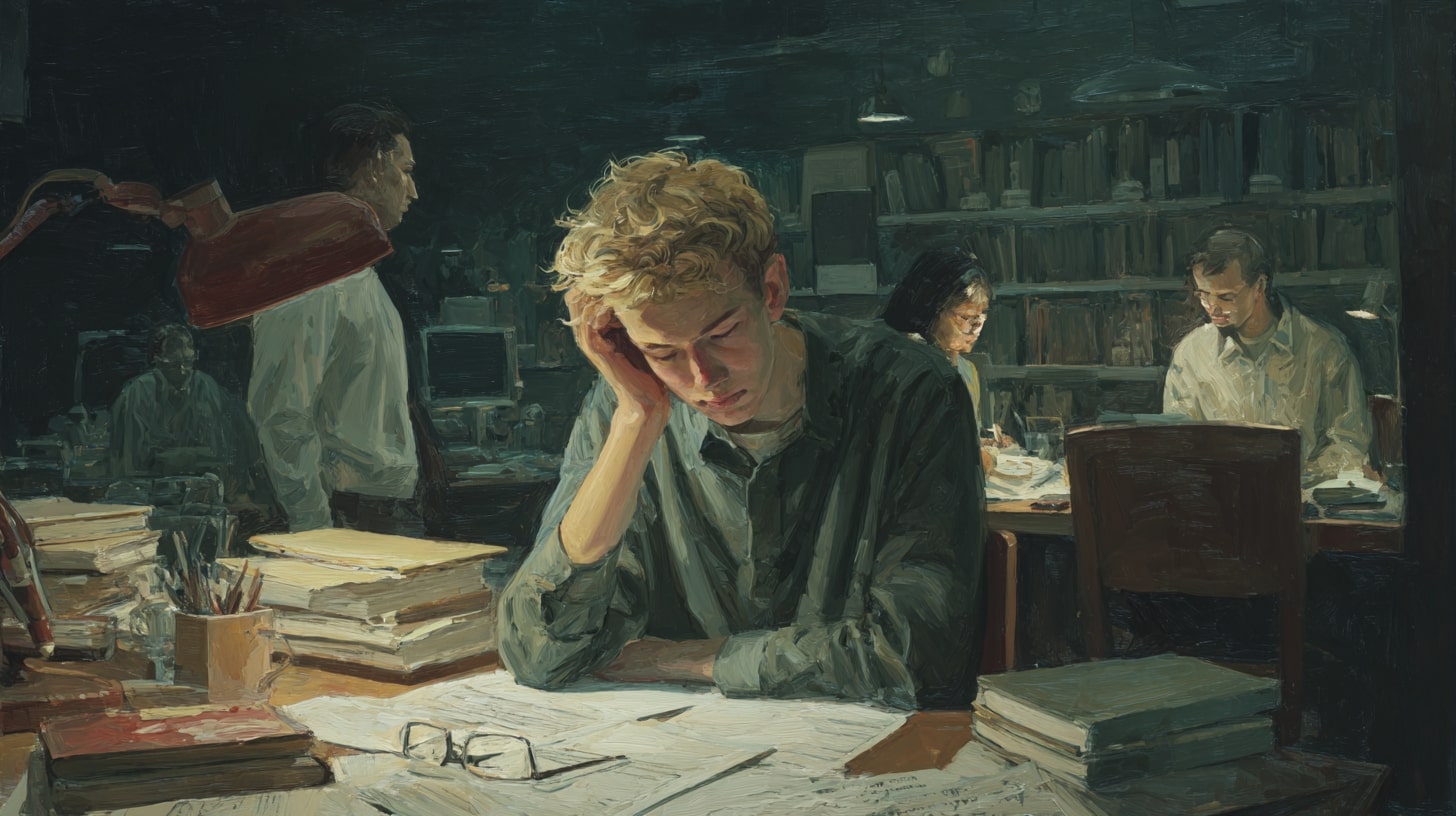

We tend to kick the day off with a look at the educational journey of student leaders – the highs and lows, the setbacks and triumphs, all in an attempt to identify the aspects that might have been caused (or at least influenced) by institutional or wider higher education policy.

And while our daft and dated student finance system, the British obsessions with going straight in and completing at top speed, or local policies on assessment or personal tutoring or extenuating circumstances all get a look in, more often than not it’s something else that has caused a problem.

It’s the way a member of staff might have responded to a question; the reaction to a student who’s loaded up with part-time work or caring responsibilities; the way in which extracurriculars are considered in a meeting on study progress; the background discussions in a misconduct panel (which, for some reason, the sector still routinely forces student leaders on to); or the way in which departmental or local discretion in policy implementation might have been handled by a given school or department.

Sometimes the differences are apparent to a student that’s well-connected, or one that’s experienced a joint award, or one that’s ended up winning their election having completed their PGT at another university (often in another country) to those who haven’t. Often, the differences are invisible.

It was especially obvious in the years that followed those “no detriment” policies that popped up during Covid. Not all ND policies were the same, but just for a moment we seemed to have moved into an era where the pace at which someone completed and the number of attempts they’d had at doing so seemed less important than whether they’d reached the required standard.

The variable speed and enthusiasm accompanying the introduction of “no detriment” policies was telling in and of itself – but more telling was the snapping back and abolition of many of the measures designed to cope with student difference and setbacks just as soon as the masking mandates were over.

Sometimes the differences are about the nuts and bolts of policies that can be changed and amended through the usual round of committee work. Sometimes they’re about differences in volumes of international students, or wild differences in the SSR that central policies pretend aren’t there. But often, especially the ones that are apparent not to them but to us, they’re differences that seem to say something about the way things are done there.

They are, in other words, about culture.

Aqui não se aprende, sobrevive-se

I’d been trying to put my finger on a way to describe a particular thread in the explanations for years – was it a misplaced notion of excellence? Something about the Russell Group, or STEM? Something about those subjects that are externally accredited, or those that fall into the “higher technical” bracket? Or was it about working with the realities of WP?

But earlier this year, I think I got close. We’d accidentally booked a cheap hotel in Lisbon for one of our study tours that just happened to be opposite Tecnico – the “higher technical” faculty of the University of Lisbon (“Instituto Superior Técnico”) that has been turfing out Portugal’s most respected engineers (in the broadest sense of the term) since 1911.

And buried in one of those strategy documents that we tend to harvest on the trips was a phrase that said it all – what students had described back in 2019 as a “meritocracia da dificuldade”, or in English, a “meritocracy of difficulty”.

Courses at Técnico were known to be hard – even one of our Uber drivers knew that – but that had in and of itself had become the institution’s defining currency. Students, staff, and alumni alike described an environment where gruelling workloads, high failure rates and dense, encyclopaedic syllabi were worn as badges of honour.

Passing through that kind of system was not just about acquiring knowledge – but about proving your ability to endure and survive, with employers reinforcing the story by recruiting almost unquestioningly on the basis of survival.

Se os alunos não aguentam, não deviam estar aqui

Academic staff featured prominently in sustaining that culture. Having themselves been shaped by the same regime, many prided themselves on reproducing it for the next generation.

Any move to reduce content, rebalance workloads, or broaden learning was interpreted as an unacceptable form of “facilitation”, “spoon feeding”, “dumbing down” or pandering. What counted, in their eyes, was difficulty itself – with rigour equated less with the quality of learning than with the sheer weight of what had to be endured.

The insistence on difficulty carried consequences for students. Its emphasis on exams, for example, meant that learning became synonymous with “studying to pass”, rather than a process of deep engagement.

The focus often fell on maximising tactics to get through, rather than on cultivating lasting understanding. In turn, students grew risk-averse – seeking out past papers, recycling lab work, and avoiding uncertainty, rather than developing the capacity to tackle open-ended problems.

O Técnico orgulha-se das reprovações

Non-technical subjects were also undervalued and looked down upon in that climate. Humanities and social sciences were frequently dismissed by staff and students alike as “soft” or “fluffy”, in contrast with the “seriousness” of technical content. That hierarchy of value both narrowed students’ horizons and reinforced the sense that only subjects perceived as hard could be respected.

It left little room for reflection on social, ethical, or cultural dimensions of high level technical education – and contributed in turn to a broader lack of extracurricular and associative engagement that caused problems later in the workplace.

And underlying all of that was the sheer pressure placed on students. The combination of high workload, repeated failure, and a culture that equated merit with suffering created an environment where wellbeing was routinely sacrificed to performance.

Scattered timetables, heavy workloads, and complex commuting patterns left little space for students to build social connections or help each other to cope. And those demanding schedules and long travel times also discouraged students from building a connection with the institution beyond the academics assessing them.

Staff, proud of having survived themselves, were routinely unsympathetic to students who struggled, and the system’s inefficiency – with many repeating units year after year – was both demoralising and costly. For some, the relentless pressure became part of their identity – for others, it was simply crushing.

As humanidades são vistas como perda de tempo. Só conta o que dói

I recognise much of what’s in the Committee on Review of Education, and Pedagogical Practices of the IST CAMEPP report in the discussions we’ve had with student leaders. We may not have the non-continuation or time-to-complete issues (although a dive into OfS’ dashboards suggests that some departments very much do) – but the “culture” issues in there very much sound familiar.

One officer told me about an academic who, when they explained they’d had to pick up more shifts in their part-time job to cover rent, sniffed and said that university “wasn’t meant for people who had to work in Tesco.”

The implication wasn’t subtle – success was contingent on being able to study full-time, with no distractions, no commitments, and no compromises. The message was that working-class students were in the wrong place.

Another described a personal tutor meeting where extracurricular involvement was treated as a sign of distraction – a dangerous indulgence. A student who had been pouring energy into running their society was solemnly advised to “park the hobbies” until after graduation, as though the skills, friendships, and confidence gained outside the classroom were worth nothing compared to a clean transcript.

The sense of suspicion towards student life beyond the lecture theatre was as striking as it was disheartening for a commuter student who’d only found friends in this way.

We’ve heard countless variations of staff dismissing pleas for help with mental health, reframing them as either “just stress” or, worse, a valuable rite of passage. One student leader said they’d been told by a tutor that “a bit of pressure builds character,” as if panic attacks were proof of academic seriousness. In that culture, resilience was demanded, but never supported.

We’ve also heard about students being told that missing a rehearsal for a hospital appointment would “set the wrong precedent,” or that seeking an extension on a piece of groupwork after a bereavement was “unfair on others.”

Others describe the quiet pressure to keep going after failing a module – not with support to improve, partly because the alternative offered was repeating the year, all with the subtle suggestion that “some people just aren’t cut out for this.” Much suggests a yearning for the students of the past – rather than a view on what the actual students need in the future.

Quando pedimos ajuda, dizem-nos que todos já passaram por isto

There are tales of students told that asking questions in lectures shows they “haven’t done the reading,” or that group work is best approached competitively rather than collaboratively – each message subtly reinforcing a culture of endurance, suspicion, and survival rather than one of learning and growth.

Then there are the stories about labs where “presenteeism” rules supreme – students dragging themselves in while feverish because attendance is policed so tightly that missing a practical feels like academic self-sabotage.

Or the sense, especially in modules assessed exclusively (or mainly) through a single high-stakes exam, that students are competing in a kind of intellectual Hunger Games – one chance, one shot, no mistakes – a structure that turns learning into a gamble, and turns peers into rivals.

Some of it is structural – student finance systems in the UK are especially unforgiving of setbacks, reductions in intensity and differences in learning pace. Some of it is about UK perceptions of excellence – the ingrained idea that second attempts can only be granted if a student fails, and even then capped, or the idea that every assessment beyond Year 1 needs to be graded rather than passed or failed, or it can’t be “excellent”.

But much of it was just about attitudes.

Facilitar seria trair a tradição do Técnico

Again and again, what has struck me hasn’t been the formal policy frameworks, but the tone of the replies students received – the raised eyebrow when someone asked about getting an extension, the sigh when a caring responsibility was mentioned, the laugh when a student suggested their part-time job was making study harder, the failure to signpost when others would.

It was the quick dismissal of a concern as “excuses,” the insistence that “everyone’s under pressure,” or the sharp rebuke that “the real world doesn’t give second chances.” To those delivering them, they may have just been off-hand comments from those themselves under pressure – but to students, they were signals, sometimes subtle, sometimes stark, about who belonged, who was valued, and what counted as legitimate struggle.

And worse, for those student leaders going into a second year, it was often a culture that was hidden. Large multi-faculty universities in the UK tend to involve multiple faculties, differing cultures and variable levels of enthusiasm towards compliance with central policies or improvement initiatives.

Almost every second-year student leader I’ve ever met can pick out one part of the university that doesn’t play ball – where the policies have changed, but the attitudes haven’t.

And they seem to know someone who was a champion for change, only to leave when confronted with the loudest voices in a department or committee that seem determined to participate only to resist it.

Menos carga lectiva, mas isso é infantilizar o ensino

Back at Tecnico, the CAMEPP commission’s diagnosis was fascinating. It argued that while Técnico’s “meritocracy of difficulty” had historically served as a guarantee of quality and employability, it had become an anachronism.

Curricula were monolithic and encyclopaedic, often privileging sheer quantity of content over relevance or applicability. The model encouraged competition over collaboration, generated high failure rates, and wasted talent by grinding down those without the stamina — or privilege — to withstand its demands.

The report argued that the culture not only demoralised students – but also limited Técnico’s global standing. In an era of rapid change, interdisciplinarity, and international mobility, the school’s rigidity risked undermining its attractiveness to prospective students and its capacity for innovation.

Employers still valued Técnico graduates, but the analysis warned that the institution was trading on its past reputation, rather than equipping students for uncertain futures.

For students, the practical impact was devastating. With teaching dominated by lectures and assessment dominated by exams, learning was often reduced to tactical preparation for high-stakes hurdles. A culture that equated merit with suffering left little space for curiosity, creativity, or critical reflection.

Non-technical subjects were trivialised, narrowing graduates’ horizons and weakening their ability to engage with the ethical, political, and social contexts in which engineers inevitably operate.

For staff, the culture had become self-perpetuating. Academics were proud of having endured the same system, and resistant to change that looked like dilution. Attempts to rebalance workloads or integrate humanities were dismissed as spoon-feeding, and student pleas for support were reframed as evidence of weakness. What looked like rigour was, in practice, an institutionalised suspicion of anything that might reduce pressure.

Temos de formar pessoas, não apenas engenheiros

Against that backdrop, the Técnico 2122 programme was deliberately framed as more than a curriculum reform. The commission argued that without tackling the underlying values and assumptions of the institution, no amount of modular tinkering would deliver meaningful change.

It set out a vision in which Técnico would be judged not only by the toughness of its courses but by the quality of its culture, the richness of its environment, and the breadth of its graduates’ capacities. The emphasis was on moving from a survival ethos to a developmental one — a school where students were expected to grow, not simply endure.

One strand of the proposals was the deliberate insertion of humanities, arts and social sciences into the heart of the curriculum. It introduced nine credits of HASS in the first cycle, including courses in ethics, public policy, international relations and the history of science – all to to disrupt the hierarchy that had long placed technical content above all else.

It was presented not as a softening of standards but as an enrichment, equipping future engineers with the critical, ethical and societal awareness to operate in a world where technical solutions always have human consequences. The language of “societal thinking” was used to capture that broader ambition — an insistence that engineering could no longer be conceived apart from the contexts in which it is deployed.

Preparado para colaborar, não apenas competir

Another aspect was a rebalancing of assessment. Instead of relying almost exclusively on high-stakes examinations, the proposals argued for a model in which exams and continuous assessment carried roughly equal weight. The aim was to break the cycle of cramming and repetition, and to create incentives for sustained engagement across the semester.

Via rewarding consistent work and collaborative projects, reforms intended to shift students away from tactical “study to pass” behaviour towards deeper and more creative forms of learning. A parallel ambition was to build more interdisciplinarity — using integrated projects and cross-departmental collaboration to replace competitive isolation with teamwork across different branches of engineering.

Just as important was the recognition that culture is shaped beyond the classroom. The plan envisaged new residences and more spaces for social, cultural and recreational activity, developed in partnership with the wider university. These weren’t afterthoughts – but central to the project, a way of countering the lack of associative life that the workload and commuting patterns had made so difficult.

And alongside new facilities came the proposal to give formal curricular recognition to extracurricular involvement — a statement that student societies, voluntary projects and civic engagement mattered as part of the Técnico experience.

The review committed to embedding both extracurricular credit and communal spaces into the fabric of the institution, all with an aim of generating a more balanced, human environment – one in which students could belong as well as perform.

And in conjunction with the SU, every programme has an academic society that students can access and get involved in – combining belonging, careers, study skills and welcome activity in a way that gives every student a community they can serve in, as well as both a representative body (rather than just a representative) at faculty and university level to both develop constructive agendas for change and bespoke student-led interventions at the right level.

At every stage, the commission stressed that this was a cultural and emotional transformation as much as it was a structural one – requiring staff and students alike to accept that the old ways no longer served them best.

Change management was presented as a challenge of mindset as much as of design. It was not enough to alter syllabi or redistribute credits – the ambition was to cultivate an atmosphere where excellence was defined by collaboration, creativity and societal contribution rather than by survival alone.

I don’t know how successful the reforms have been, or whether they’ve met the ambitions set in the astonishingly long review document. But what I do know is they found inspiration from higher technical universities and faculties from around the world:

- Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands had been experimenting with “challenge-based” learning, where interdisciplinary teams of students work on open-ended, real-world problems with input from industry and civic partners.

- ETH Zurich in Switzerland had sought to rebalance its exam-heavy culture by integrating continuous assessment and project work, with explicit emphasis on collaboration and reflection rather than competition alone.

- Aalto University in Finland had deliberately merged technology, business, and arts to break down disciplinary silos, embedding creativity and design into engineering programmes and fostering a stronger culture of interdisciplinarity.

- Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden had restructured large parts of its curriculum around project-based learning, placing teamwork and sustained engagement at the centre of assessment instead of single high-stakes hurdles.

- Technical University of Munich (TUM) had introduced entrepreneurship centres, interdisciplinary labs, and credit for extracurricular involvement to underline the learning and innovation often happen outside formal classrooms.

- And École Polytechnique in Paris had sought to rebalance its notoriously demanding technical curriculum with a stronger grounding in humanities and social sciences, aiming to cultivate graduates able to navigate the societal dimensions of scientific and technological progress.

Criatividade e contributo, não apenas sobrevivência

There are real lessons here. I’ve talked before about the way the autonomous branding and decision-making in the faculty at Lison surfaces higher technical in a way that those who harp on about 1992 and the abolition of polytechnics can’t see back in the UK.

But the case study goes further for me. On all of the “student focussed” agendas – mental health, disability, commuters, diversity, there’s invariably a working group and a policy review where one or more bits of a university won’t, don’t and never will play ball.

A couple of decades of focus on the “student experience” have seen great strides and changes to the way the sector supports students and scaffolds learning. But most of those working in a university know that yet another review won’t change that one bit – especially if its research figures are strong and it’s still recruiting well.

Part of the problem is the way in which student culture fails to match up to the structures of culture in the modern UK university. 1,500 course reps is a world of difference to associative structures at school, faculty or department level. Both universities and SUs have much to learn from European systems about the way in which the latter cause issues of retention, or progression or even just recruitment to be “owned” by student associations.

Some of it is about course size. What we think of as a “course” would be one pathway inside much bigger courses with plenty of choice and optionality in Europe. The slow erosion of elective choice in the UK makes initiatives like those seen elsewhere harder, not easier – but who’s brave enough to go for it when every other university seems to have 300 programme leaders rather than 30?

But it’s the faculty thing that’s most compelling. What Técnico’s review shows is that a faculty can take itself seriously enough to undertake a searching cultural audit – not just compliance with a curriculum refresh, but a root-and-branch reflection on what it means to be educated there, in the context of the broader discipline and the way that discipline is developing around the world.

It raises an obvious question – why don’t more faculties here do the same? Policy development in the UK almost always happens at the university level, often driven by external regulatory pressure, and usually framed in language so generic that it misses the sharp edges of disciplinary culture.

But it’s the sharp edges – the tacit assumptions about what counts as “hard” or “serious”, the informal attitudes of staff towards struggling students, the unspoken hierarchies of value between technical and social subjects – that so often define the student experience in practice.

A review of the sort that Técnico and others undertook forces the assumptions into the open. It makes it harder for a department to dismiss humanities as “fluffy” or to insist that wellbeing struggles are just rites of passage when the evidence has been gathered, collated, and written down.

It gives students’ unions a reference point when they argue for cultural change, and it creates a shared vocabulary for both staff and students to talk about what the institution is, and what it wants to be. That kind of mirror is uncomfortable – but it’s also powerful.

And if nothing else, the review reminds us that culture is not accidental. It is constructed, transmitted, and defended – sometimes with pride, sometimes with inertia. The challenge is whether faculties here might be brave enough to interrogate their own meritocracies of difficulty, to ask whether the traditions they prize are really preparing students for the future, or whether they are just reproducing a cycle of survival.

That’s a process that can’t be delegated up to the university centre, nor imposed by a regulator. It has to come from within – which makes me wonder whether finding those students and staff who find the culture where they work oppressive need to be surfaced and connected – before the usual suspects (that are usually suspect) do the thing they always do, and preserve rather than adapt.