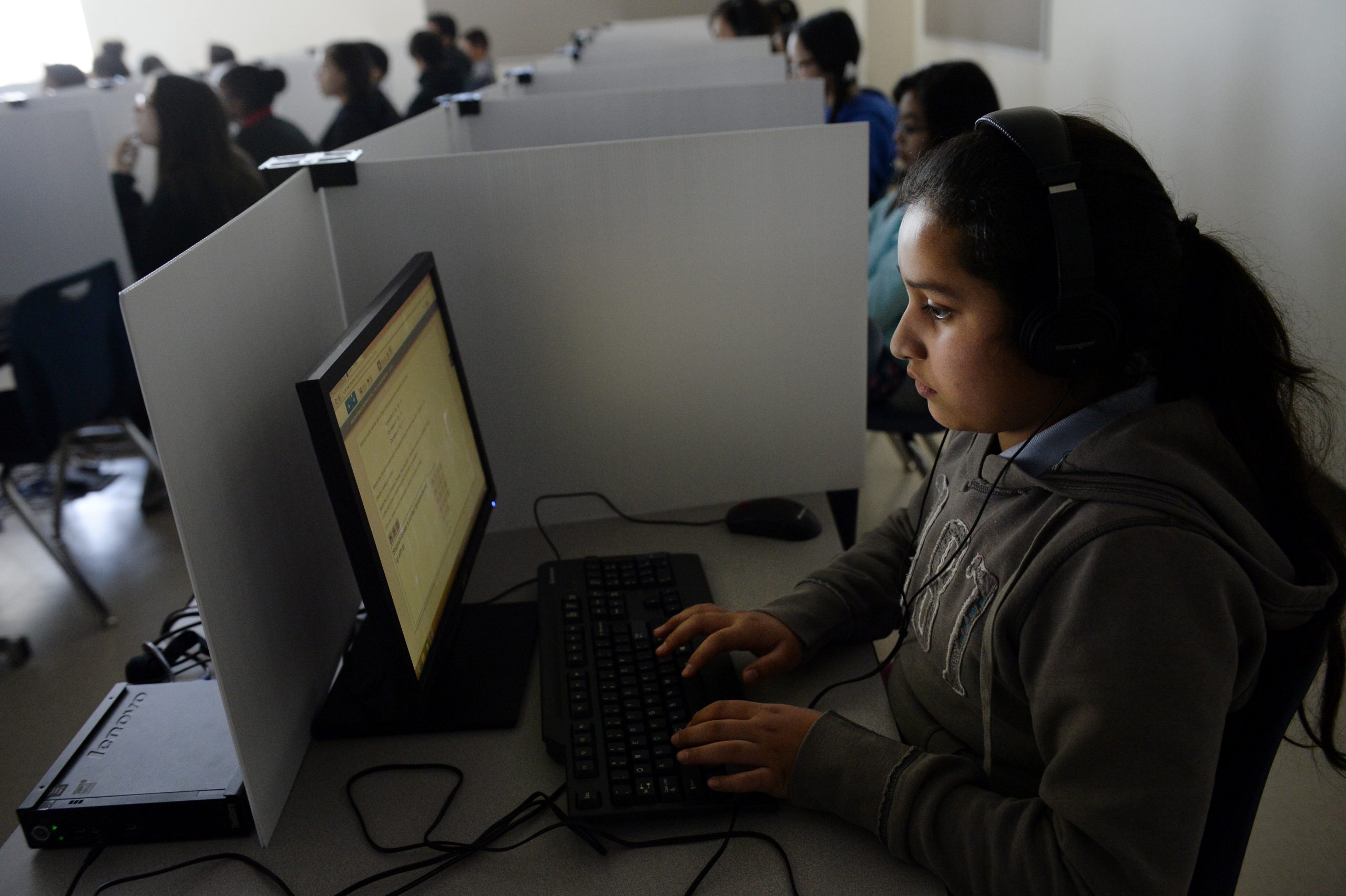

Picture this: you’ve crossed oceans, packed your suitcase, a dictionary (or maybe just Google Translate), your dreams, and a relentless drive to succeed in a US higher education setting. You’ve landed in the United States, ready for college life. But before you can even start worrying about your academic experience or how to navigate campus life and groceries you’re hit with a more personal challenge: “Will I sound awkward if I say this out loud?”

For many non-native English speakers, this is not just a fleeting thought. It’s a daily reality known as foreign language anxiety – “the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second language contexts, including speaking, listening, and learning.” It can limit and negatively impact a student’s ability to communicate, threaten self-confidence, and, over time, affect academic performance.

Why it matters more than we think

Foreign language anxiety is more than a minor inconvenience. International students must maintain full-time enrolment to keep their visa status. If foreign language anxiety leads to missed classes, delayed assignments, or low grades, the consequences can be severe — including losing that status and returning home without a degree.

Even though incoming students meet minimum language proficiency requirements, many have had little practice using English in real-life spontaneous situations. Passing a standardised test is one thing; responding to a professor’s question in front of a class of native speakers is another. This gap can lead to self-consciousness, fear, and avoidance behaviours that hinder academic and social success.

The three faces of language anxiety

Research shows that foreign language anxiety often takes three forms:

- Fear of negative evaluation – Worrying about being judged for language mistakes, whether by professors or peers. Some students are comfortable in class but avoid informal conversations. Others avoid eye contact entirely to escape being called on.

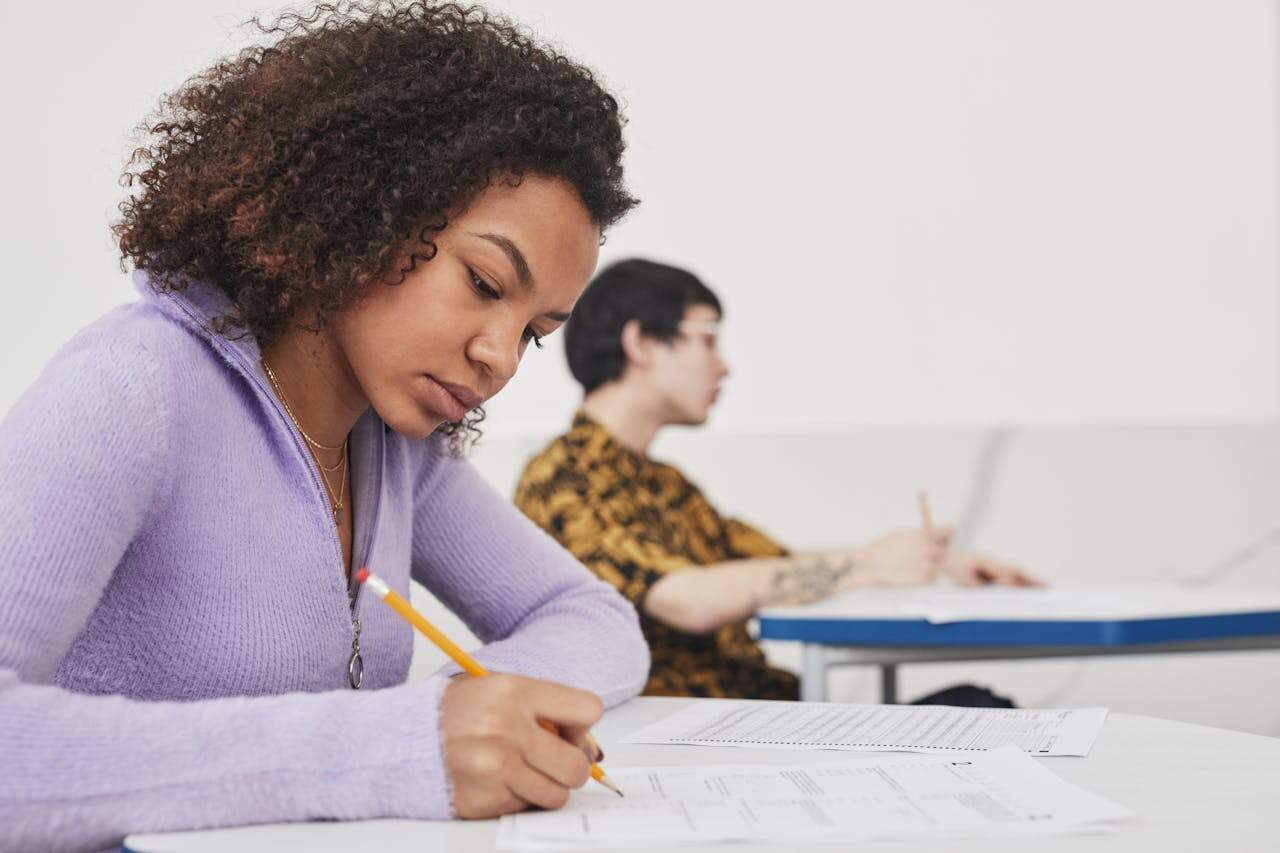

- Communication apprehension – Feeling uneasy about speaking in a foreign language, even for students who were confident communicators in their home country. Concerns about sounding less capable than native speakers can lead to silence in classroom discussions.

- Test anxiety – Stress about organising and expressing ideas under time pressure in a second language. This is not just about knowing the material; it’s about performing under linguistic and cognitive strain.

These anxieties can actively block learning. When students focus on how they sound rather than what is being said, their ability to process information suffers.

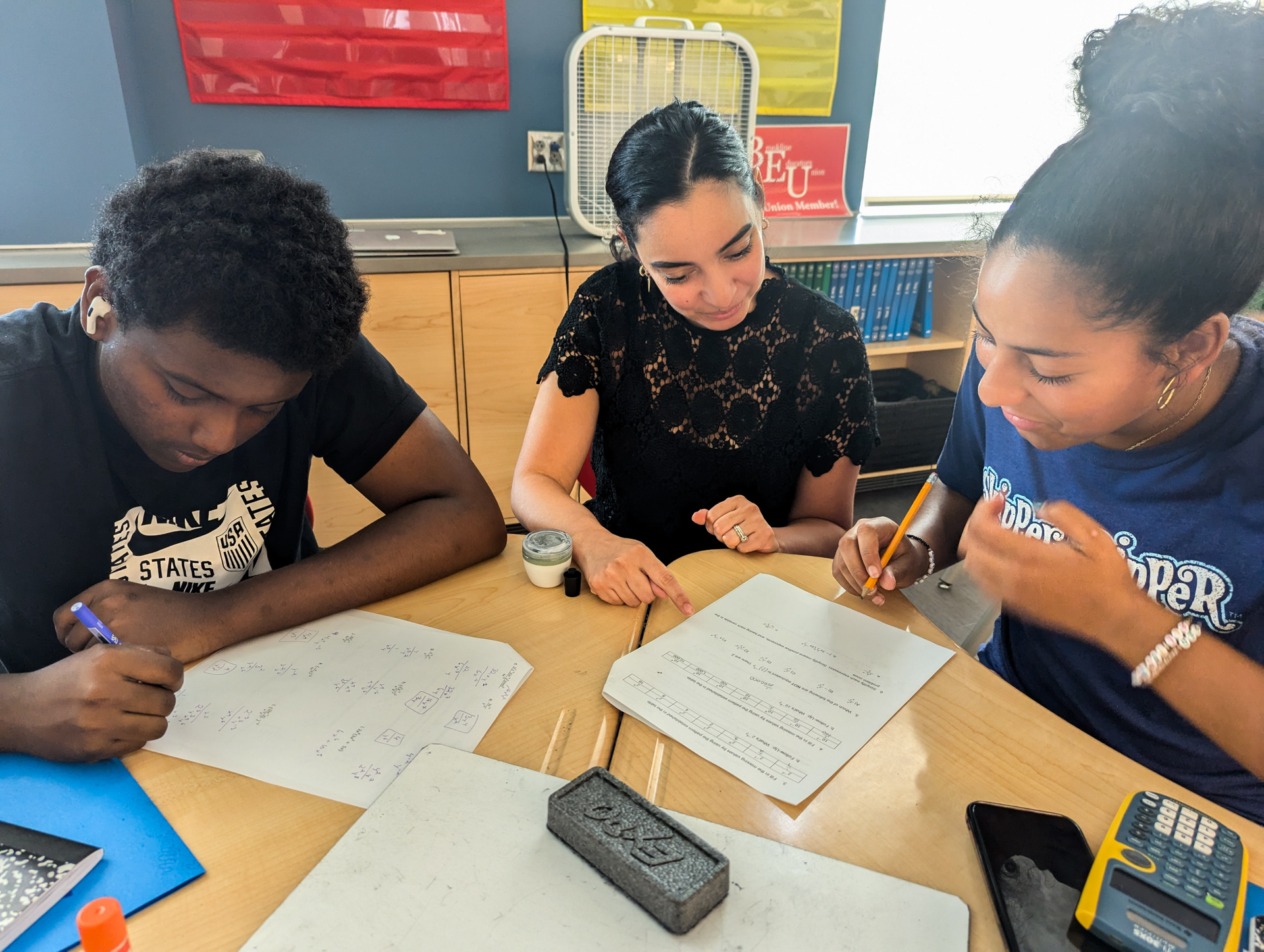

The role of faculty and administrators

Faculty and administrators may underestimate how much their approach affects international students’ confidence. Being corrected for grammar in front of others is one of the most anxiety-provoking experiences students report. In contrast, giving students time to answer, offering feedback privately, and creating an environment where mistakes are treated as part of learning can significantly reduce foreign language anxiety.

When capable, motivated students are held back by the effects of foreign language anxiety, institutions risk losing both talent and the global perspectives these students offer

University administrators can also make a difference through peer mentoring programs, conversation workshops, and targeted support services. However, these resources are only effective if students are aware of them and feel comfortable using them.

Why this isn’t just a student problem

It’s easy to think of foreign language anxiety as a personal obstacle each student must overcome, but it has larger implications. International students bring global perspectives, enrich classroom discussions, and contribute to campus culture.

Their success is both a moral responsibility and an investment in the overall quality and strength of higher education. When capable, motivated students are held back by the effects of foreign language anxiety, institutions risk losing both talent and the global perspectives these students offer. Taking steps to reduce its impact benefits the entire academic community.

Moving forward

Addressing foreign language anxiety is not about lowering academic standards. It’s about giving students a fair chance to meet them by reducing unnecessary barriers. For students, this means practicing conversation in low anxiety provoking settings, seeking clarification when needed, and accepting that mistakes are a natural part of language learning. For faculty and staff, it means being intentional about communication, offering encouragement, and ensuring that resources are accessible and culturally responsive.

Foreign language anxiety is a shared challenge that can undermine even the most motivated and capable students. Often, the greatest hurdle of studying abroad is not mastering complex coursework, adjusting to life far from home, or navigating cultural differences – it is the moment a student must raise their hand, speak in a language that is not their own, and hope that their words are understood as intended.

Beyond academics, foreign language anxiety can affect the kinds of social and academic engagement that are essential for building leadership skills. Group work, class discussions, and participation in student organisations often require students to communicate ideas clearly, respond to feedback, and collaborate across cultures – the same skills needed to lead effectively in professional environments.

However, literature on foreign language anxiety suggests that students may hesitate to take on visible roles or avoid speaking in group settings altogether, limiting their ability to practice these skills. When students withdraw from such opportunities, they lose more than a chance to participate – they miss experiences that can shape confidence, decision-making, and the ability to work with diverse teams.

Understanding and addressing the impact of foreign language anxiety, therefore, is not only relevant for academic success but also for preparing graduates to step into leadership roles in a global context.