Months after U.S. President Donald Trump suddenly cut U.S. international assistance for the prevention and treatment of AIDS and the HIV virus that leads to it, the ripple effects are now changing health programs — and opening new debates — around the world.

More than US$2.5 billion has been stripped from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief or PEPFAR, the major U.S. funding stream for global treatment, prevention and research of AIDS.

In 2025, the U.S. National Institutes of Health terminated 191 specific grants for programs to prevent and treat HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. That’s a funding loss of more than $200 million, and more cuts seem likely in the 2026 budget.

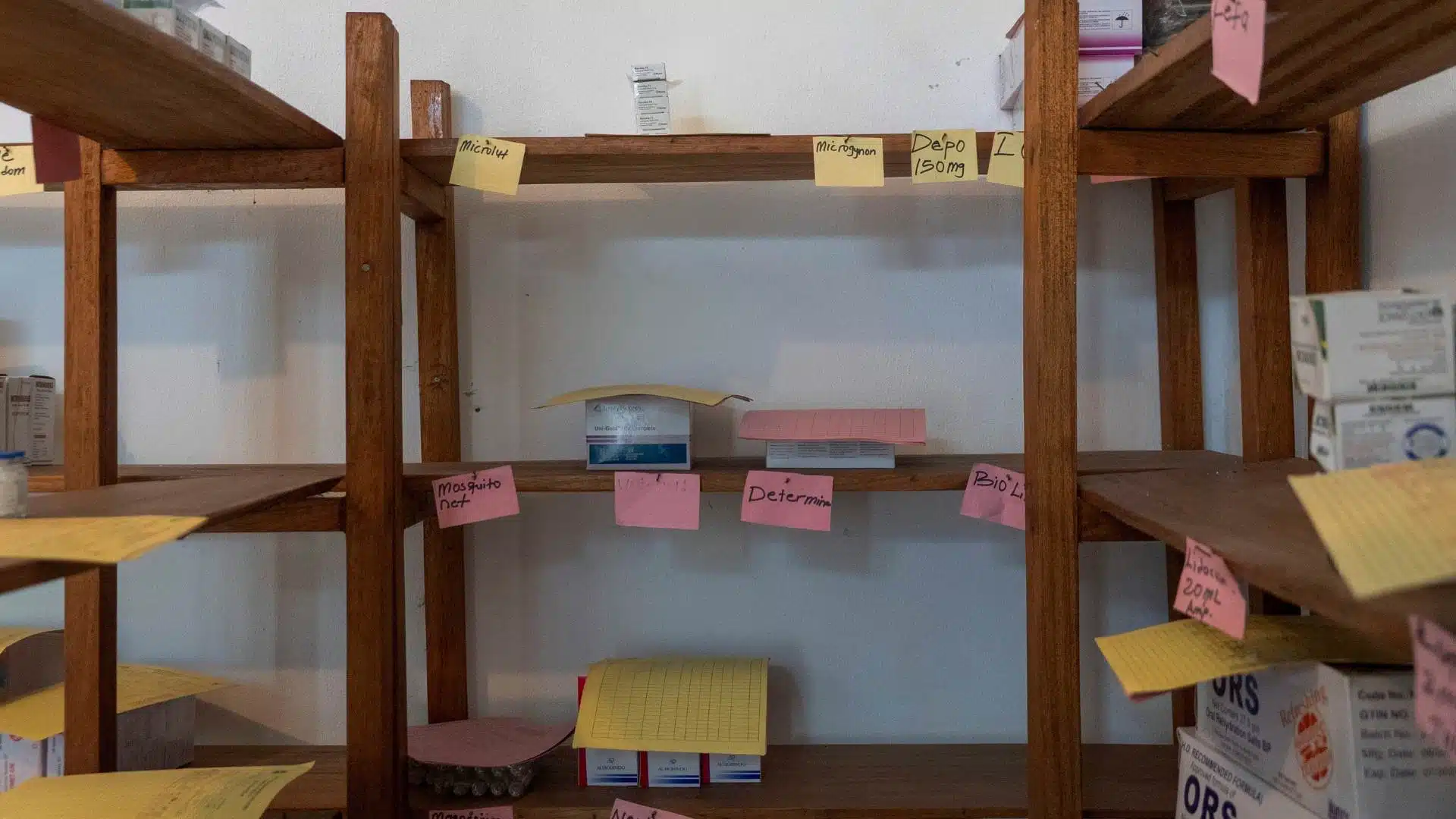

Among the casualties of the funding cuts: two million adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa no longer have access to a program that offered services for HIV prevention, sexual and reproductive health and protection from physical sexual violence as well as education and empowerment.

Also in jeopardy: prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV through counseling, testing, preventive therapy, early diagnosis in infants and pediatric treatment services.

Halting HIV treatment

All this leaves tens of thousands of doctors, nurses and support staff in Kenya, South Africa and Mozambique without needed support. Almost all U.S.-supported research programs on HIV vaccines and tuberculosis were halted.

Some governments have responded. Ethiopia, for example, imposed new taxes to pay salaries of workers previously covered by U.S.-funded projects. Patients who were treated at community-based clinics are now being referred to government-run facilities.

The aid cutoff has hobbled one of the world’s greatest public health triumphs: about 31.5 million people in treatment around the world, according to the World Health Organization.

This has helped avoid the apocalyptic visions of entire generations — mainly of young and productive people — lost to this scourge. The United Nations estimates that 1.3 million people acquired HIV last year. That marks a 40% drop globally and 56% in Sub-Saharan Africa, between 2010 and 2024.

In all, HIV/AIDS has killed more than 44 million people since its emergence in the mid-80s, including 630,000 last year, demonstrating the need for continued HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and research.

Transformational treatment

The U.S. pullback comes just as a game-changing prevention drug is entering the market: Lenacapavir is a long-acting drug administered twice a year.

But instead of a rapid scale-up of a transformational treatment, the overall cuts in U.S. aid across all diseases could lead to 14 million additional deaths over five years according to a projection in the medical journal Lancet.

UNAIDS has warned that without replacement funding, the PEPFAR cuts could result in an extra six million HIV infections and four million more AIDS-related deaths by 2029.

The UN agency has urged countries to transform their HIV responses. Other nations have started to step in. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria has collected pledges of US$11.34 billion from governments and $1.3 billion from private donors, of which $912 million is coming from the Gates Foundation.

An argument is gaining momentum that the crisis is a blessing in disguise for nations and programs that have come to rely too much on U.S. money.

The world working together

Each protracted health threat — Ebola, Mpox, COVID-19 — makes the case for self-reliance and a system of enhanced regional cooperation and collaboration that leverages international agreements such as the International Health Regulations and the WHO Pandemic Treaty while respecting national sovereignty.

Consider the G20 Health Working Group. It brings together all the countries in the G20 — a forum of the world’s largest economies — plus collaboration with the World Health Organization, World Bank and other partners to strengthen global health systems, promote universal health coverage and coordinate responses to major health challenges.

It aims at building resilient, equitable and sustainable health systems worldwide. The G20 Global Health Group has in recent years focused on funding gaps and investments needed to meet 2030 targets: health inequities between high and low-income countries and responses to climate change and migration pressures on health systems.

The ultimate idea is to integrate health with humanitarian, peace and development goals by, among other things, adopting a primary health care approach; strengthening human resources for health; stemming the tide of Non-Communicable Diseases; enhancing pandemic prevention, preparedness and response; and supporting science and innovation for health and economic growth to accelerate health equity, solidarity and universal access.

Restoring, sustaining and scaling-up coverage of essential HIV/AIDS prevention, care, treatment and protection services through countries and communities’ self reliance will be a major indicator of this commitment.

Questions to consider:

1. How can the elimination of U.S. health funding be a “blessing in disguise” for African nations?

2. Why has the funding of HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention around the world been considered a success story?

3. How might access to health treatment be a problem where you live?