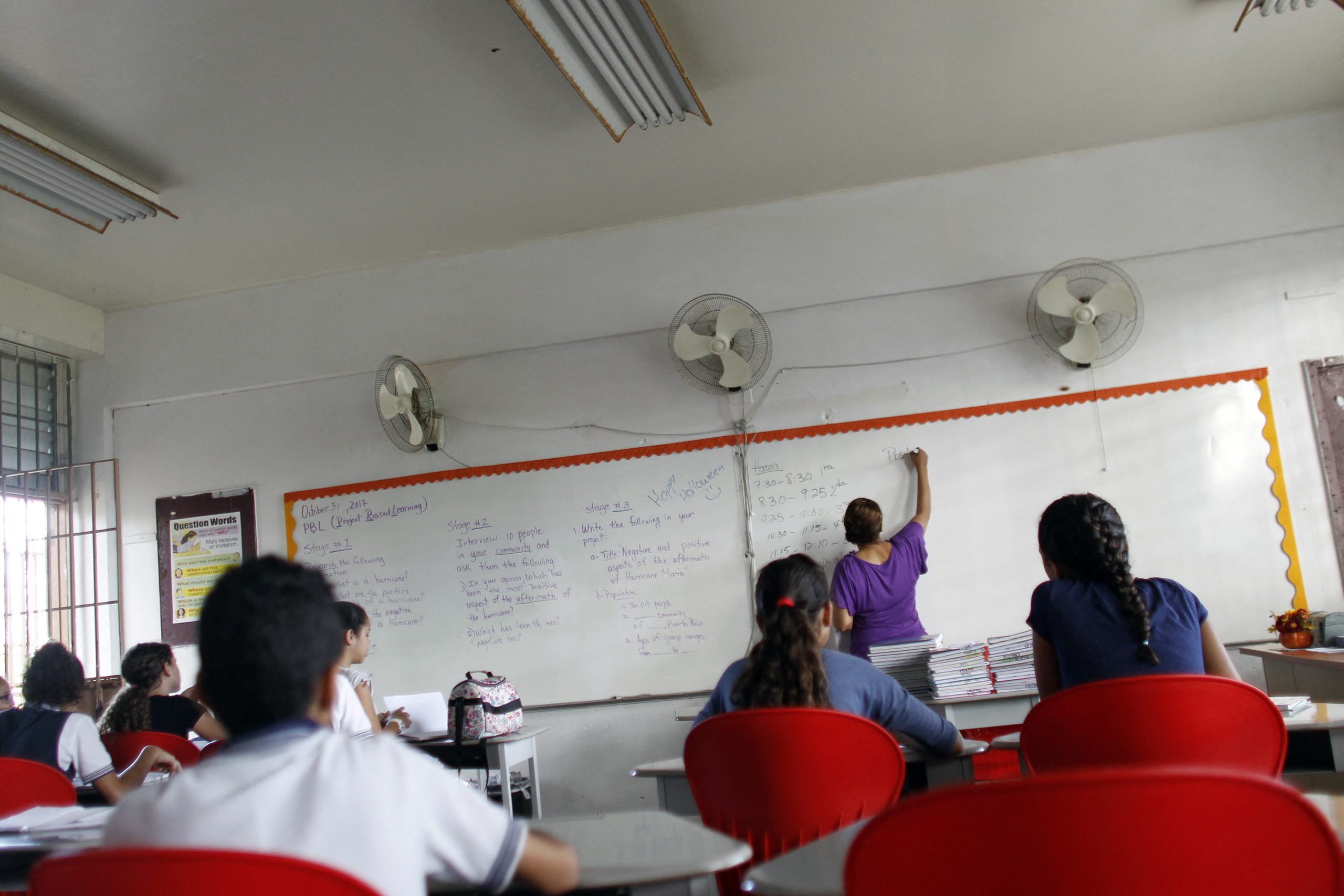

Maraida Caraballo Martínez es educadora en Puerto Rico desde hace 28 años y directora de la Escuela de la Comunidad Jaime C. Rodríguez desde hace siete. Nunca sabe cuánto dinero recibirá del gobierno cada año porque no se basa en el número de niños matriculados. Un año recibió 36.000 dólares; otro año, 12.000 dólares.

Pero por primera vez como educador, Caraballo notó una gran diferencia durante la administración Biden. Gracias a una inyección de fondos federales en el sistema educativo de la isla, Caraballo recibió una subvención de 250.000 dólares, una cantidad de dinero sin precedentes. La utilizó para comprar libros y ordenadores para la biblioteca, pizarras e impresoras para las aulas, reforzar el programa de robótica y construir una pista polideportiva para sus alumnos. “Esto significó una gran diferencia para la escuela”, dijo Caraballo.

Yabucoa, un pequeño pueblo del sureste de Puerto Rico, fue una de las regiones más afectadas por el huracán María en 2017. Y esta comunidad escolar, como cientos de otras en la isla, ha experimentado trastornos casi constantes desde entonces. Una serie de desastres naturales, como huracanes, terremotos, inundaciones y deslizamientos de tierra, seguidos de la pandemia de coronavirus en 2020, han golpeado la isla e interrumpido el aprendizaje. También ha habido una rotación constante de secretarios de educación locales: siete en los últimos ocho años. El sistema educativo puertorriqueño -el séptimo distrito escolar más grande de Estados Unidos- se ha vuelto más vulnerable debido a la abrumadora deuda de la isla, la emigración masiva y una red eléctrica paralizada.

Relacionado: En las aulas de preescolar a secundaria pasan muchas cosas. Mantente al día con nuestro boletín semanal gratuito sobre educación.

Bajo la presidencia de Joe Biden, se produjeron tímidos avances, respaldados por miles de millones de dólares y una atención personal sostenida por parte de altos funcionarios federales de educación, dijeron muchos expertos y educadores de la isla. Ahora les preocupa que todo se desmantele con el cambio en la Casa Blanca. El presidente Donald Trump no ha ocultado su desdén por el territorio estadounidense, habiendo dicho supuestamente que estaba “sucio y que la gente era pobre.” Durante su primer mandato, retuvo miles de millones de dólares en ayuda federal tras el huracán María y ha sugerido vender la isla o cambiarla por Groenlandia.

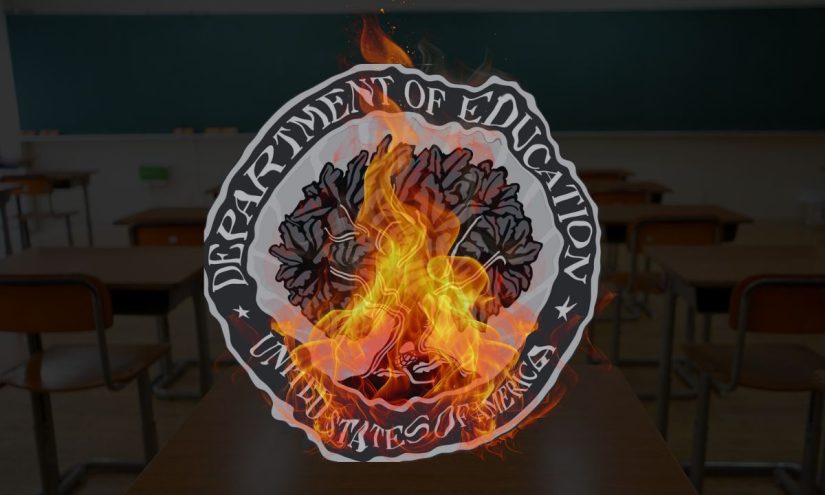

Una reciente orden ejecutiva para hacer del inglés el idioma oficial ha preocupado a los habitantes de la isla, donde solo 1 de cada 5 personas habla inglés con fluidez, y el español es el idioma de instrucción en las escuelas. Trump está tratando de eliminar el Departamento de Educación de EE.UU. y ya ha hecho recortes radicales a la agencia, lo que tendrá implicaciones en toda la isla. Incluso si los fondos federales -que el año pasado representaron más de dos tercios del financiamiento del Departamento de Educación de Puerto Rico, o DEPR- se transfirieran directamente al gobierno local, probablemente traerían peores resultados para los niños más vulnerables, dicen los educadores y expertos en políticas públicas. Históricamente, el DEPR ha estado plagado de interferencias políticas, burocracia generalizada y falta de transparencia.

Y el departamento de educación local no está tan avanzado tecnológicamente como otros departamentos de educación estatales, ni es tan capaz de difundir las mejores prácticas. Por ejemplo, Puerto Rico no dispone de una “fórmula por alumno”, un cálculo utilizado habitualmente en el continente para determinar la cantidad de dinero que recibe cada estudiante para su educación. Roberto Mujica es el director ejecutivo de la Junta de Supervisión y Gestión Financiera de Puerto Rico, convocada por primera vez bajo la presidencia de Barack Obama en 2016 para hacer frente al marasmo financiero de la isla. Mujica dijo que la actual asignación de fondos educativos de Puerto Rico es opaca. “Cómo se distribuyen los fondos se percibe como un proceso político”, dijo. “No hay transparencia ni claridad”.

En 2021, Miguel Cardona, Secretario de Educación de Biden, prometió “un nuevo día” para Puerto Rico. “Durante demasiado tiempo, los estudiantes y educadores de Puerto Rico fueron abandonados”, dijo. Durante su mandato, Cardona aignó casi 6.000 millones de dólares federales para el sistema educativo de la isla, lo que se tradujo en un aumento salarial histórico para los profesores, financiamiento para programas de tutoría extraescolar, la contratación de cientos de profesionales de salud mental escolar y la creación de un programa piloto para descentralizar el DEPR.

Cardona designó a un asesor principal, Chris Soto, para que fuera su persona de contacto con el sistema educativo de la isla, subrayando el compromiso del gobierno federal con la isla. Durante casi cuatro años en el cargo, Soto realizó más de 50 viajes a la isla. Carlos Rodríguez Silvestre, director ejecutivo de la Fundación Flamboyán, una organización sin fines de lucro de Puerto Rico que ha dirigido los esfuerzos de alfabetización infantil en la isla, dijo que el nivel de respeto e interés sostenido hicieron sentir que se trataba de una asociación, no un mandato de arriba hacia abajo. “Nunca había visto ese tipo de atención a la educación en Puerto Rico”, afirmó. “Soto prácticamente vivía en la isla”.

Soto también trabajó estrechamente con Víctor Manuel Bonilla Sánchez, presidente del sindicato de maestros, la Asociación de Maestros de Puerto Rico, o AMPR, lo que dio lugar a un acuerdo por el que los educadores recibieron 1.000 dólares más al mes en su salario base, un aumento de casi el 30% para el maestro promedio. “Fue el mayor aumento salarial en la historia de los maestros de Puerto Rico”, dijo Bonilla, aunque incluso con el aumento, los maestros de aquí siguen ganando mucho menos dinero que sus colegas en el continente.

Una de las mayores quejas que Soto dijo haber escuchado fue lo rígido y burocrático que era el Departamento de Educación de Puerto Rico, a pesar de una ley de reforma educativa de 2018 que permite un mayor control local. La agencia de educación -la unidad de gobierno más grande de la isla, con la mayor cantidad de empleados y el mayor presupuesto- estaba configurada de manera que la oficina central tenía que aprobar todo. Así que Soto creó y supervisó un programa piloto en Ponce, una región en la costa sur de la isla, enfocado en la descentralización.

Por primera vez, la comunidad local eligió un consejo asesor de educación, y los candidatos a superintendente tuvieron que postularse en lugar de ser nombrados, dijo Soto. El superintendente recibió autoridad para aprobar directamente las solicitudes presupuestarias en lugar de enviarlas a través de funcionarios de San Juan, así como flexibilidad para gastar el dinero en su región en función de las necesidades de cada escuela.

En el pasado, eso no se tenía en cuenta: Por ejemplo, Yadira Sánchez, psicóloga que lleva más de 20 años trabajando en la educación puertorriqueña, recuerda cuando una escuela recibió docenas de aires acondicionados nuevos aunque no los necesitaba. “Ya tenían aires acondicionados que funcionaban”, dice, “así que ese dinero se perdió”.

Relacionado: Las amenazas de deportación de Trump pesan sobre los grupos que ofrecen ayuda con la FAFSA

El proyecto piloto también se centró en aumentar la eficiencia. Por ejemplo, ahora se evalúa a los niños discapacitados en sus colegios, en lugar de tener que acudir a un centro especial. Y Soto dice que también intentó eliminar el uso de influencias y aumentar la transparencia en torno al gasto en el PRDE. “Puedes mejorar las facturas, pero si tus amigos políticos son los que se quedancon los trabajos, entonces no tienes un buen sistema escolar”, dijo.

Bajo el mandato de Biden, Puerto Rico también recibió una subvención competitiva o grant del Departamento de Educación de EE.UU. por valor de 10,5 millones de dólares para escuelas comunitarias, otro hito. Y el departamento federal empezó a incluir datos sobre el territorio en algunas estadísticas educativas recopiladas. “Puerto Rico ni siquiera figuraba en estos indicadores, así que empezamos a preguntarnos cómo mejorar los sistemas de datos. Desentrañar el problema de los datos significó que Puerto Rico puede ser debidamente reconocido”, dijo Soto.

Pero ya hay planes para deshacer el esfuerzo de Cardona en Ponce. La recién elegida gobernadora de la isla, Jenniffer González Colón, es republicana y partidaria de Trump. El popular secretario de Educación, Eliezer Ramos Parés, regresó a principios de este año al frente del departamento tras dirigirlo desde abril de 2021 hasta julio de 2023, cuando la gobernadora le pidió inesperadamente que dimitiera, algo nada inusual en el gobierno de la isla, donde los nombramientos políticos pueden terminar de repente y con poco debate público. Ramos dijo a The Hechinger Report que el programa no continuará en su forma actual, calificándolo de “ineficiente”.

“El programa piloto no es realmente eficaz”, dijo, señalando que la política puede influir en las decisiones de gasto no sólo a nivel central, sino también a nivel regional. “Queremos tener algunos controles”. También dijo que ampliar la iniciativa a toda la isla costaría decenas de millones de dólares. En su lugar, Ramos dijo que estaba estudiando enfoques más limitados de la descentralización, en torno a algunas funciones de recursos humanos y adquisiciones. Dijo que también estaba explorando una fórmula de financiación por alumno para Puerto Rico y estudiando las lecciones de otros grandes distritos escolares como la ciudad de Nueva York y Hawai.

Aunque la educación ha sido la mayor partida presupuestaria de la isla durante años, sigue siendo mucho menos de lo que cualquiera de los 50 estados gasta en cada estudiante. Puerto Rico gasta 9.500 dólares por estudiante, frente a una media de 18.600 dólares en los estados.

El Departamento de Educación de EE.UU., que complementa la financiación local y estatal para los estudiantes en situación de pobreza y con discapacidades, tiene un papel desproporcionado en las escuelas de Puerto Rico. En la isla, el 55% de los niños viven por debajo del umbral de la pobreza, frente al 17% en los 50 estados; en el caso de los estudiantes de educación especial, las cifras son del 35% y el 15%, respectivamente. En total, durante el año fiscal 2024, más del 68 por ciento del presupuesto de educación en la isla procede de fondos federales, frente al 11 por ciento en los estados de EE UU. El departamento también administra las becas Pell para estudiantes de bajos ingresos -alrededor del 72 por ciento de los estudiantes puertorriqueños las solicitan- y apoya los esfuerzos de desarrollo profesional y las iniciativas para los niños puertorriqueños que van y vienen entre el continente y el territorio.

Linda McMahon, la nueva secretaria de Educación de Trump, ha dicho supuestamente que el Gobierno seguirá cumpliendo sus “obligaciones legales” con los estudiantes aunque el departamento cierre o transfiera algunas operaciones y despida personal. El Departamento de Educación de Estados Unidos no respondió a las solicitudes de comentarios para esta historia.

Algunos dicen que el hecho de que la administración Biden haya vertido miles de millones de dólares en un sistema educativo en problemas con escasa rendición de cuentas ha creado expectativas poco realistas y no hay un plan para lo que ocurre después de que se gasta el dinero. Mujica, director ejecutivo de la junta de supervisión, dijo que la infusión de fondos pospuso la toma de decisiones difíciles por parte del gobierno puertorriqueño. “Cuando se tiene tanto dinero, se tapan muchos problemas. No tienes que enfrentarte a algunos de los retos que son fundamentales para el sistema”. Y afirmó que apenas se habla de lo que ocurrirá cuando se acabe ese dinero. “¿Cómo se va a llenar ese vacío? O desaparecen esos programas o tendremos que encontrar la financiación para ellos”, dijo Mujica.

Dijo que esfuerzos como el de Ponce para acercar la toma de decisiones a donde están las necesidades de los estudiantes es “de vital importancia”. Aún así, dijo que no está seguro de que el dinero haya mejorado los resultados de los estudiantes. “Esta era una gran oportunidad para hacer cambios fundamentales e inversiones que produzcan resultados a largo plazo. No estoy seguro de que hayamos visto las métricas que lo respalden”.

Relacionado: ¿Un trabajo demasiado bien hecho?

Puerto Rico es una de las regiones más empobrecidas desde el punto de vista educativo, con unos resultados académicos muy inferiores a los del continente. En la parte de matemáticas de la Evaluación Nacional de Progreso Educativo, o NAEP, una prueba que realizan los estudiantes de todo EE.UU., sólo el 2% de los alumnos de cuarto curso de Puerto Rico calificaron como competentes, la puntuación más alta jamás registrada en la isla, y el 0% de los alumnos de octavo curso lo fueron. Los estudiantes puertorriqueños no hacen la prueba NAEP de lectura porque aprenden en español, no en inglés, aunque los resultados compartidos por Ramos en una conferencia de prensa en 2022 mostraron que sólo el 1% de los estudiantes de tercer grado leían a nivel de grado.

Hay algunos esfuerzos alentadores. La Fundación Flamboyán ha liderado una coalición de 70 socios en toda la isla para mejorar la alfabetización de los niños de preescolar a tercer grado, entre otras cosas mediante el desarrollo profesional. La formación del profesorado a través del departamento de educación del territorio ha sido a menudo irregular u opcional.

La organización trabaja ahora en estrecha colaboración con la Universidad de Puerto Rico y, como parte de ese esfuerzo, supervisa el gasto de 3 millones de dólares en formación para la alfabetización. Aproximadamente 1.500 profesores de Puerto Rico (un tercio de los maestros de Kinder a 5º grado) han recibido esta rigurosa formación. Los educadores recibieron 500 dólares como incentivo por participar, además de libros para sus aulas y tres horas de formación continua. “Fueron muchas horas de calidad. No ha sido el método de ‘rociar (con un poco de agua) y rezar’”, dijo Silvestre. Ese esfuerzo continuará, según Ramos, que lo calificó de “muy eficaz”.

Una nueva prueba de lectura para alumnos de primero a tercer grado que la organización sin fines de lucro ayudó a diseñar mostró que entre los años escolares 2023 y 2024, la mayoría de los niños estaban por debajo del nivel del grado, pero hubo avances en los resultados en todos los grados. “Pero aún nos queda un largo camino por recorrer para que estos datos lleguen a los profesores a tiempo y de forma que puedan actuar en consecuencia”, dijo Silvestre.

Kristin Ehrgood, Directora General de la Fundación Flamboyán, afirma que es demasiado pronto para ver resultados espectaculares. “Es realmente difícil ver una tonelada de resultados positivos en un período tan corto de tiempo con la desconfianza significativa que se ha construido durante años”, dijo. Dijo que no estaban seguros de cómo la administración Trump podría trabajar o financiar el sistema educativo de Puerto Rico, pero que la administración Biden había construido una gran cantidad de buena voluntad. “Hay muchas oportunidades que podrían aprovecharse, si una nueva administración decide hacerlo”.

Otra señal esperanzadora es que la junta de supervisión, que fue muy protestada cuando se formó, ha reducido la deuda de la isla de 73.000 a 31.000 millones de dólares. Y el año pasado los miembros de la junta aumentaron el gasto en educación en un 3%. Mujica dijo que la junta se centra en asegurarse de que cualquier inversión se traduzca en mejores resultados para los estudiantes: “Nuestra opinión es que los recursos tienen que ir a las aulas”.

Betty A. Rosa, comisionada de educación y presidente de la Universidad del Estado de Nueva York y miembro de la Junta de Supervisión, afirmó que la inestabilidad educativa en Puerto Rico se debe a los cambios en el liderazgo. Cada nuevo líder se dedica a “reconstruir, reestructurar, reimaginar, elija la palabra que elija”, dijo. “No hay coherencia”. A diferencia de su cargo en el estado de Nueva York, el Secretario de Educación de Puerto Rico y otros cargos son nombramientos políticos. “Si tienes un gobierno permanente, aunque cambie el liderazgo, el trabajo continúa”.

Ramos, que vivió esta inestabilidad cuando el anterior gobernador pidió inesperadamente su dimisión en 2023, dijo que se reunió con McMahon, la nueva secretaria de Educación de EE.UU., en Washington, D.C., y que mantuvieron una “agradable conversación”. “Ella sabe de Puerto Rico, se preocupa por Puerto Rico y demostró total apoyo en la misión de Puerto Rico”, dijo. Dijo que McMahon quería que el DEPR ofreciera más clases bilingües, para exponer a más estudiantes al inglés. Queda por ver si habrá cambios en la otorgación de fondos o cualquier otra cosa. “Tenemos que ver lo que ocurre en las próximas semanas y meses y cómo esa visión y esa política podrían afectar a Puerto Rico”, dijo Ramos.

Ramos fue muy apreciado por los educadores durante su primera etapa como Secretario de Educación. También tendrá que tomar muchas decisiones, como ampliar las escuelas charter y cerrar las escuelas públicas tradicionales, ya que la matriculación en las escuelas públicas de la isla sigue disminuyendo vertiginosamente. En el pasado, ambas cuestiones provocaron protestas feroces y generalizadas.

Soto es realista y cree que la nueva administración tendrá “puntos de vista diferentes, tanto ideológica como políticamente”, pero confía en que el pueblo de Puerto Rico no quiera volver a la antigua forma de hacer las cosas. “Alguien dijo: ‘Ustedes sacaron al genio de la botella y va a ser difícil volver a ponerlo’ en lo que se refiere a un sistema escolar centrado en el estudiante”, dijo Soto.

Cardona, cuyos abuelos son oriundos de la isla, dijo que Puerto Rico había experimentado un “estancamiento académico” durante años. “No podemos aceptar que los estudiantes rindan menos de lo que sabemos que son capaces”, dijo a The Hechinger Report, justo antes de despedirse como máximo responsable de educación del país. “Empezamos el cambio; tiene que continuar.

La pequeña escuela de la directora Carabello, con 150 alumnos y 14 profesores, ha estado a punto de cerrarse ya tres veces, aunque en todas ellas se ha salvado en parte gracias al apoyo de la comunidad. Carabello confía en que Ramos, con quien ya ha trabajado anteriormente, cambie las cosas. “Conoce el sistema educativo”, afirma. “Es una persona brillante, abierta a escuchar”.

Pero las largas jornadas de los últimos años le han pasado factura. Suele estar en la escuela de 6:30 a.m. a 6:30 p.m. “Entras cuando anochece y te vas cuando anochece”, dice. Ha habido muchas plataformas nuevas que aprender y nuevos proyectos que poner en marcha. Quiere jubilarse, pero no puede permitírselo. Tras décadas en las que el gobierno local no financió suficientemente el sistema de pensiones, se recortaron los subsidios que compensaban el alto precio de los bienes y servicios en la isla y se congelaron los planes de pensiones.

Ahora, en lugar de jubilarse con el 75% de su salario, Carabello recibirá sólo el 50%, 2.195 dólares al mes. Tiene derecho a prestaciones de la Seguridad Social, pero no son suficientes para compensar la pensión perdida. “¿Quién puede vivir con 2.000 dólares en un mes? Nadie. Es demasiado duro. Y mi casa aún necesita 12 años más para pagarse”.

A Carabello, siempre tan fuerte y optimista con sus alumnos, se le saltaron las lágrimas. Pero es raro que se permita tiempo para pensar en sí misma. “Tengo una gran comunidad. Tengo grandes profesores y me siento feliz con lo que hago”, afirma.

Está muy, muy cansada.

Comunícate con editora Caroline Preston al 212-870-8965 o [email protected].

Este artículo sobre el Departamento de Educación y Puerto Rico fue producido por The Hechinger Report, una organización de noticias independiente sin fines de lucro centrada en la desigualdad y la innovación en la educación. Suscríbete a nuestro boletín de noticias.