In New York City, a surprising culinary shift is happening where few expect it: inside city agencies that serve up to 219 million meals and snacks a year. From hospitals to shelters, New York is quietly leading a global experiment to reshape the diets of millions, not by persuasion but through policy.

Food is sitting at the crossroads of two global crises: chronic disease and climate change. The World Health Organization estimates that in 2017, 11 million deaths were attributable to unhealthy diets that were high in processed meat, sodium and added sugar and low in fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

Climate change, in addition to the consequences of extreme weather events, makes existing challenges worse on communities, environments and systems that sustain life.

More than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas, where 70% of global CO2 emissions are generated from transport, buildings and energy use. According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, roughly 1.7 billion people living in cities and areas around them face food insecurity, making cities the new frontline in the fight against malnutrition.

The report calls on governments to use public budgets to buy and serve healthier food, prioritize buying from local, agroecological and small-scale farmers and integrate food planning into urban policies on health, transport, housing and waste.

We are what we eat.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, how people live — what they eat, how they move and what goods they consume — matters just as much as what governments do. Some governments, like New York’s, are turning sustainable living from a personal choice into a shared system: using their purchasing power to serve millions of plant-forward meals that put vegetables, legumes and grains at the center of the plate across public institutions, and coupling procurement with education and food policy to make diets a driver of both health and sustainability.

This makes these cities critical testing grounds for climate solutions, where policies that reshape diets toward more plant-rich, low-carbon meals can contribute directly to urban emissions reduction while improving health.

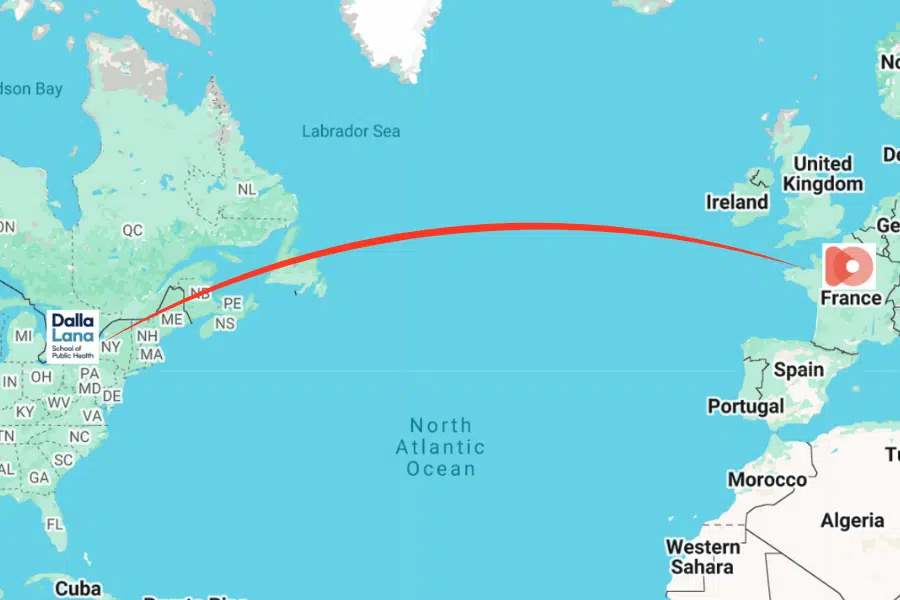

Since signing the C40 Good Food Cities Declaration in 2019, mayors across the world have pledged to make healthy and sustainable eating the norm by buying food aligned with the Planetary Health Diet, which promotes serving more plant-based meals, cutting food waste by half and working across communities, businesses and institutions to integrate these goals into their climate action plans.

New York is not alone. In Copenhagen, kitchen staff across more than 500 public kitchens are being trained to prepare nutritious, organic and climate-friendly meals as the city works toward its goal of making 90% of its food organic. In Quezon City in the Philippines, a partnership with Scholars of Sustenance, a nonprofit environmental organization tackling food waste, helped recover and distribute surplus food, providing roughly 22,000 meals for people in need within the first four months of the program. Across the world, cities are rethinking how the meals served through public programs can nourish both people and the planet.

In 2021, New York launched an ambitious 10-year plan with five goals: to support food businesses and strengthen protections for food workers; to modernize supply chains; to provide food that is produced, distributed and disposed of sustainably; to promote community engagement and cross-sector co-ordination; and to improve the nutrition and food security of New Yorkers.

Building health into a food system

The city’s updated Food Standards go further: They ban processed meats and deep frying, require two or more servings a week at lunch and dinner to feature plant proteins and limit beef and other meats, such as lamb and mutton, to a maximum of two servings a week at facilities serving three meals a day. These standards touch nearly every corner of city life; they guide what’s served in schools, hospitals, homeless shelters, correctional facilities and senior centers, which adds up to 219 million meals and snacks each year.

New York challenges the idea that sustainable diets are solely individual choices, reframing them as civic responsibility.

“Food standards are the reinforcement piece for our departments and agencies to align with those values,” said Ora Kemp, senior policy adviser in the Office of the Mayor of New York City. “So those get developed with a very clear and distinct goal of being able to promote, protect and preserve the health of those that we serve through our food service, while simultaneously ensuring that the food is delicious and is culturally representative of the people that we serve.”

Transparency is also a central tool in this transformation. The Good Food Purchasing initiative, established in 2022, requires vendors to share data, such as the origin of the food and meals the city buys.

The lesson of the city’s policies for the public’s health is simple: People embrace change when it still feels like home.

“We have a policy that if 20% of the population is of any religious or ethnic group, then we need to make sure that food is provided for that group,” says Lorraine Cortés-Vásquez, commissioner of the New York City Department for the Aging. “It is very important for us that we manage the requirements, but also look at demand, interest and palate, because we want to respect culture and respect traditions, but we also want people to consume the food.”

Sustainable food choices

In a citywide Cook-Off hosted by the Department for the Aging, chefs came together to demonstrate the flavor, creativity and nutrition of plant-based food, while also bringing the community together.

“Most older adults want to live in the community, in the communities that they build,” Cortés-Vásquez said. “They’re an asset, they bring revenue.”

Kemp said that plant-based menu options are also a low-effort way to encourage sustainable food choices.

“It’s not just the first and not just the second [exposure], but we offer the plant-based default multiple times throughout someone’s stay within any of our health and hospital systems in an attempt to encourage them to choose healthier diets,” Kemp said.

Preliminary data from New York City Health and Hospitals demonstrate that the shift is clear: 90% of patients who received plant-based meals report satisfaction.

Nicole Bonica, deputy director of menu management at the Office of Food and Nutrition Services for New York City Public Schools, says success depends on building a menu that students also like and that they feel will benefit them. This can be tricky. “Older students, they have preferences,” Bonica said. “Girls may not want to eat so many calories, because they’re watching themselves, whereas the boys actually want more protein items, maybe because they’re in more athletics.”

The success of Plant-Powered Fridays, where school cafeterias feature a plant-based dish as the primary menu item, has led to additional offerings of plant-powered meals throughout the week in schools. Rich in vitamins, minerals, fiber and protein, these meals must align with both New York City Food Standards and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

While this experiment is still unfolding, city governments may offer the most hopeful ingredient of all: changing what a city eats can change what a city stands for. In kitchens that once served convenience, chefs now serve climate action, health and dignity on the same plate. If New York can make sustainability taste good, perhaps the rest of the world can too.

Questions to consider:

1. How is food connected to climate change?

2. What is one thing New York City is doing to get young people to eat healthier?

3. Can you think of ways you could change your diet to make it healthier?