Higher education is not like other sectors. One way in which this is apparent is the different terminology used for the leadership roles in universities and colleges. Let’s have a look.

Firstly, who’s in charge? If you look at UK universities’ governance documents, often the highest office by precedent is the chancellor. The word chancellor, I find, comes from old French, and was the court usher who controlled access to the monarch or to judges, the term coming from cancellus, or lattice work, being the bars in the screen dividing the king/judge from hoi polloi.

But chancellors in universities are nowadays honorary and ceremonial roles, although at first they probably did more day-to-day. For example, Oxford’s first chancellor may have been appointed in 1201, its first vice chancellor in 1230. There’s twenty-nine years of stuff to be done between those dates, and the chancellor must have been in the frame for doing some of that.

In any event, chancellors are now ceremonial. But they have pro-chancellors and vice chancellors. Both terms mean, literally, on behalf of the chancellor, but from different Latin roots. Pro chancellor roles tend to be chair of the university’s governors, but do not play a part in the executive leadership of the university. Vice chancellor roles are – almost universally – the executive leader of the university.

(Incidentally, vice in the meaning of “on behalf of” was one of the first university Latin words I learnt. In my first job, at Senate House, University of London, minutes would record, for example, “Dr Bloggs vice Dr Smith” – that is, Dr Smith had sent a substitute. I never learnt Latin at school, on account of attending the ur-bog-standard comprehensive in Sheffield, so I’ve picked it up from working in universities, where it remains the first language for some.)

You’ll also meet pro in pro-vice chancellors; sadly it’s not in this sense the opposite of am, like in pro-am golf tournaments. Add in deputy and you can have deputy pro-vice chancellor, which is a little like assistant chief to the chief assistant.

Moving back up the ladder, there’s a trend for some universities now to have a vice chancellor who is also president. This follows the US usage, where the head of institution is sometimes the chancellor, and sometimes the president. The issue, apparently, was that on some trips overseas, US hosts would wonder why they were only talking to an assistant, not to the CEO. So being vice chancellor and president is becoming more common, particularly but not exclusively, I think, in Russell Group universities.

And in colleges you have many titles. As I noted, I started my career in higher education at the University of London, and there you have a provost, a rector, a master, a warden, several principals, several directors, and several presidents, sometimes just president and sometimes president and something else. All of this stems from the individual history of the colleges: for example, Goldsmiths’ warden title comes from the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, which supported its foundation back in the day.

And I bet you think that I’ve forgotten Scotland, which, of course, has a different history, with four universities established before union with England in 1707. And in Scotland principal is the dominant title for the head of institution. Twelve have principals (and probably principles as well), five have vice chancellor and principals, and one has a director. Scotland also has several rectors, but these aren’t the head of institution like the rector of Imperial (or indeed of Sunderland Polytechnic as was) but are a ceremonial figurehead elected by students.

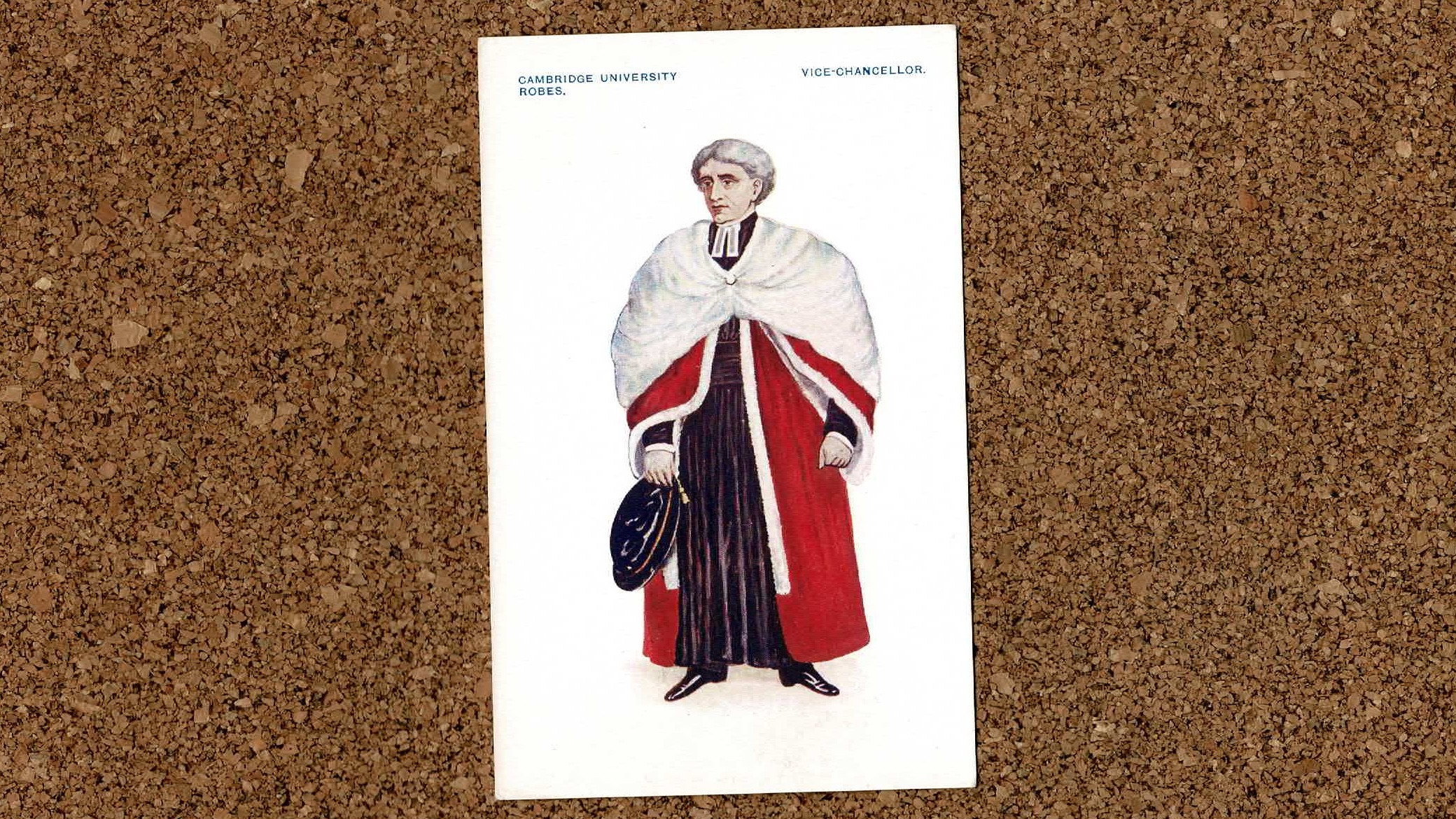

Here’s a jigsaw of the postcard. It hasn’t been sent, so I can’t put a specific date on it.

And is it an actual person? Eyeballing the potential candidates, I think it might be a portrait of Arthur James Mason, Professor of Divinity, Master of Pembroke College 1903–12, and Vice Chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1908–10.