A polarized electorate

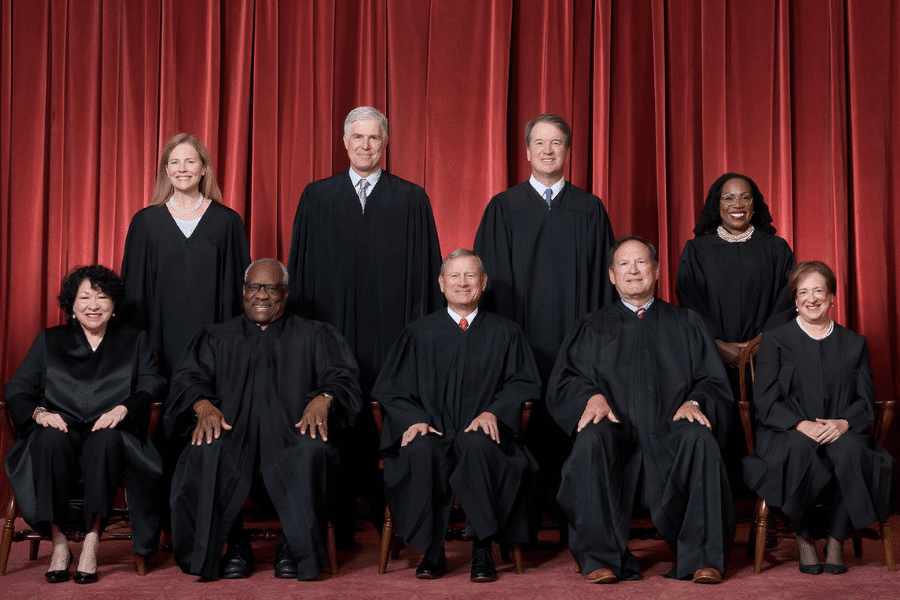

The first Italo-American to serve on the Supreme Court, Scalia had been appointed by Ronald Reagan, a Republican president. Of the eight remaining justices, four were appointed by Republican presidents and four by Democrats.

Both parties recognize that Scalia’s successor could tip the scales in close votes. Cases currently before the Court involve climate change, affirmative action, abortion, unions, immigrants and contraception — issues where the electorate is deeply divided.

Although the Constitution stipulates that the president nominates Supreme Court justices, Republican candidates for the presidency have said the choice of Scalia’s successor should be left to whoever succeeds Barack Obama in the White House next January. Obama, a Democrat, has said he will send a nomination to the Senate in due course.

That partisan split can be explained by the weight of the Court’s decisions and the polarization of the U.S. electorate.

Whereas historically the two major parties have been able to agree, sometimes begrudgingly, on the choice of justices, the process has become far more partisan and divisive in recent decades.

Unfavorable opinions

The gaping ideological split in the current Congress and an increasingly vitriolic presidential campaign ensure a bitter fight in coming months.

The political acrimony was reflected in a nationwide poll conducted last year by the Pew Research Center.

Following recent Supreme Court rulings on Obamacare and same-sex marriage, unfavorable opinions of Court have reached a 30-year high, the survey found. And opinions about the court and its ideology have never been more politically divided.

“Republicans’ views of the Supreme Court are now more negative than at any point in the past three decades,” it said. Little wonder that Republican presidential candidates are keen to put a conservative in the vacant seat.

While the Supreme Court is an independent branch of government, its composition is not — and has never been — immune from politics. The nomination of justices is part of the system of checks and balances.

But at the end of the day, the system requires the willingness of voters and their representatives to adhere to laws, executive orders and court rulings, however deep the political divide. If that faith ever crumbled, the U.S. experiment in democracy would be under threat.