The ambush shooting of two National Guardsmen near the White House on November 27, 2025, by Rahmanullah Lakanwal, a 29-year-old Afghan national, is the latest in a growing wave of politically motivated violence that has engulfed the United States since 2024. Lakanwal opened fire on uniformed service members stationed for heightened security, wounding both. Federal authorities are investigating whether ideological motives drove the attack, which comes against a backdrop of escalating domestic and international tensions. This ambush cannot be understood in isolation. It is part of a larger pattern of domestic political violence that has claimed lives across ideological lines.

Conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated at Utah Valley University during a campus event in September 2025. Minnesota state representative Mary Carlson and her husband were murdered in their home by a man impersonating law enforcement, while a state senator and spouse were injured in the same spree. Governor Josh Shapiro survived an arson attack on his residence earlier this year. Even Donald Trump was the target of an assassination attempt in July 2024. Added to this grim tally are incidents such as the 2025 Manhattan mass shooting, in which young professionals, including two Jewish women, Julia Hyman and Wesley LePatner, were killed, and the Luigi Mangione case, in which a former student allegedly killed a corporate executive in New York. Together, these incidents reveal a nation in which lethal violence increasingly intersects with politics, identity, and ideology.

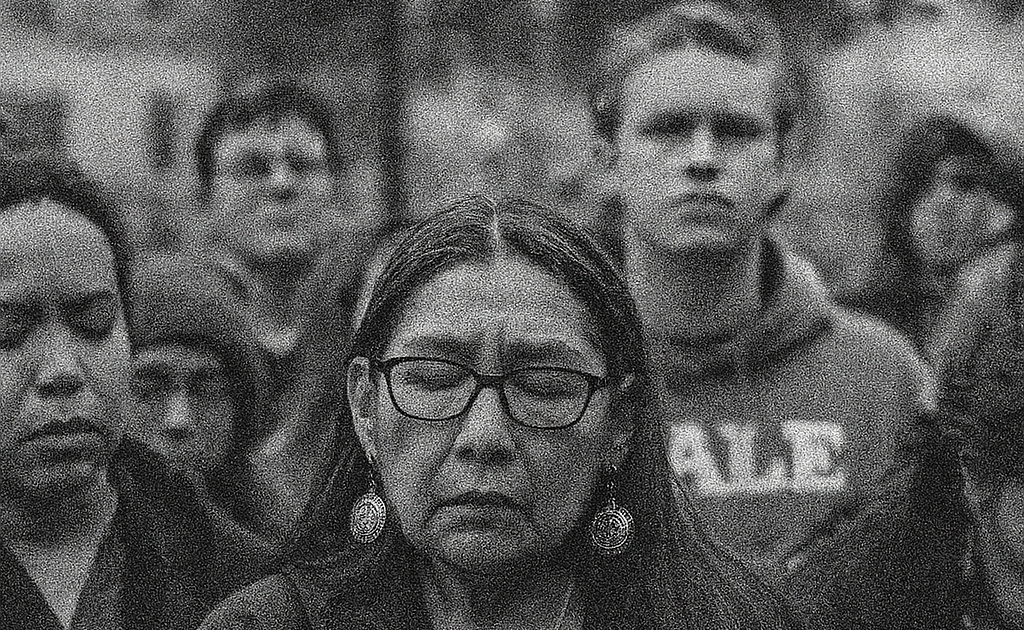

The domestic escalation of violence cannot be separated from broader structures of oppression. Migrants and asylum seekers face detention, family separation, and deportation under the authority of ICE, often in conditions described as inhumane, creating fear and vulnerability among refugee communities. Routine encounters with law enforcement disproportionately harm Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other marginalized communities. Excessive force and lethal policing add to communal distrust, reinforcing perceptions that violence is a sanctioned tool of the state. Political rhetoric compounds the problem. President Trump and other political leaders have repeatedly framed immigrants, political opponents, and even students as threats to national security, implicitly legitimizing aggressive responses and providing fodder for extremist actors.

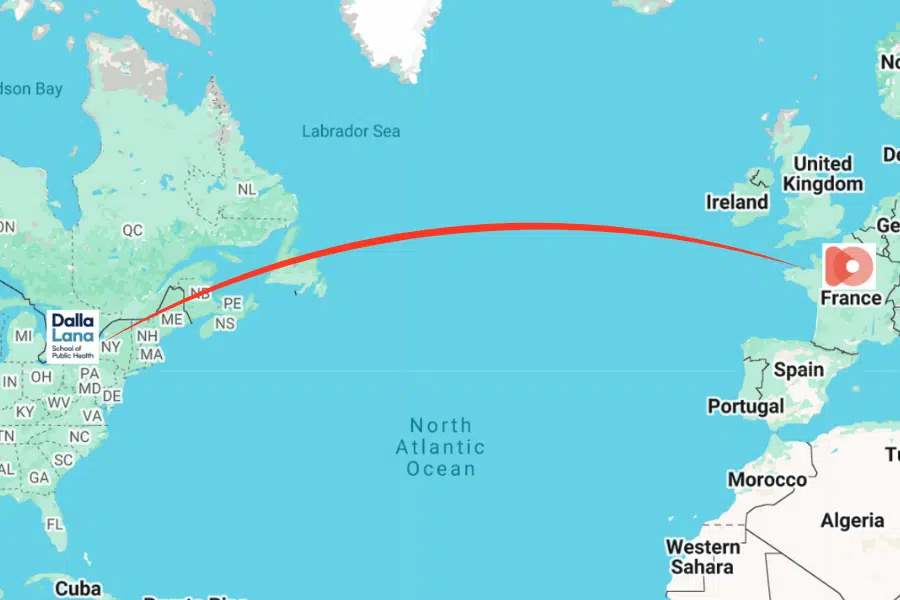

The domestic situation is further complicated by U.S. foreign policy, which has often contributed to global instability while modeling the use of violence as an instrument of governance. In Palestine, military aid to Israel coincides with attacks on civilians and infrastructure that human-rights organizations describe as ethnic cleansing or genocide. In Venezuela, U.S. sanctions, threats, and proxy operations have intensified humanitarian crises and political instability. Complicity with the governments of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Russia enables human-rights abuses abroad while emboldening domestic actors who mimic state-sanctioned violence. These global policies reverberate at home, influencing public discourse, shaping extremist narratives, and creating a climate in which political and ideological violence is increasingly normalized.

Higher education sits at the nexus of these domestic and global pressures. Universities and colleges are not merely observers; they are active participants and, in some cases, victims. The assassination of Charlie Kirk on a campus underscores that institutions of learning are no longer insulated from lethal political conflict. Alumni, recent graduates, and professionals—such as the victims of the Manhattan shooting—are affected even after leaving school, revealing how closely academic networks intersect with broader societal risks. International and refugee students, particularly from Afghan and Middle Eastern communities, face heightened anxiety due to restrictive immigration policies, anti-immigrant rhetoric, and the real threat of violence. Faculty teaching topics related to immigration, race, U.S. foreign policy, or genocide are increasingly targeted by harassment, threats, and institutional pressures that suppress academic freedom. The cumulative stress of political violence, systemic oppression, and global conflicts creates trauma that universities must address comprehensively, both for students and faculty.

Higher education cannot prevent every act of violence, nor can it resolve the nation’s deep political fractures. But it can model ethical and civic engagement, defending inquiry and speech without succumbing to fear or political pressure. It can extend support to vulnerable communities, promote critical thinking about the domestic roots of political violence and the consequences of U.S. foreign policy, and foster ethical reflection that counters the normalization of aggression. Silence or passivity risks complicity. Universities must recognize that the threats affecting campuses, alumni, and students are interconnected with broader systems of power and oppression, both domestic and global.

From the White House ambush to Charlie Kirk’s assassination, from the Minnesota legislators’ murders to the Manhattan mass shooting, from Luigi Mangione’s high-profile killing to systemic violence enforced through ICE and police overreach, and amid the influence of incendiary political rhetoric and U.S. complicity in violence abroad, the United States is experiencing an unprecedented convergence of domestic and international pressures. Higher education sits at the center of these converging forces, and how it responds will shape not only campus safety and academic freedom but also the broader civic health of the nation. The challenge is immense: to uphold democratic values, protect communities, and educate students in a society increasingly defined by fear, extremism, and violence.

Sources

Reuters. “FBI probes gunman’s motives in ambush shooting of Guardsmen near White House.” The Guardian. Coverage on suspect identification and political reaction. AP News. Statements by national leaders following attacks. Washington Post. Analysis of domestic violent extremism and political violence trends. People Magazine. Reporting on Minnesota legislator assassination. NBC/AP. Statements by Gov. Josh Shapiro after Charlie Kirk’s killing. Utah Valley University and local ABC/Fox affiliates on the Kirk shooting. Jewish Journal, ABC7NY. Coverage of Manhattan mass shooting and Jewish victims. Reuters. Luigi Mangione case and court proceedings. Human Rights Watch / Amnesty International reports on Palestine, Venezuela, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. Brookings Institute. Analysis of political violence and domestic extremism. CSIS. “Domestic Extremism and Political Violence in the United States.”