Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

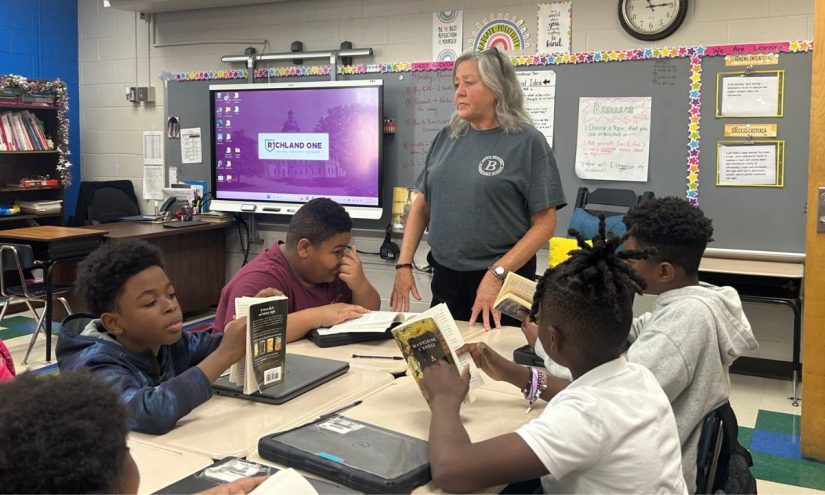

I see it every fall: A student suddenly needs to go to the bathroom mid-lesson. Another zones out completely, distracting nearby classmates during a lesson. Tears well up as a child struggles with a problem they just can’t get through.

These are the telltale signs of math anxiety creeping back into my classroom, and it’s heartbreakingly common. Between 70% and 78% of students experience a decline in math skills over the summer across elementary grades. By the time they reach fifth grade, students can lag behind their peers by two to three years.

That means students are missing out on crucial math skills that form the foundation for everything that comes later. As many teachers can attest, math remains one of the hardest subjects to teach because the basics aren’t always as black and white as they seem.

I’ve had to look for new ways to break down those barriers and ease the pressure. That’s why I’ve leaned into game-based learning. It takes something stressful and makes it approachable. In teaching math, that makes all the difference.

I first brought games into my math block because I wanted to try something different. A student suggested we review a concept with a math game he had used, and I decided to give it a shot.

There are plenty of games: Math Reveal, Quizizz and Coolmath among them. In my class we use Prodigy, which allows students to play as wizards exploring different fantasy worlds. They progress through the game by engaging in math-based quests and battles, answering a series of math questions to power spells, cast attacks or heal their wizard. Behind the scenes, the platform analyzes each student’s strengths and gaps, then adjusts and tailors content to the appropriate learning level.

The benefits were clear almost immediately, and the atmosphere in my classroom shifted. Kids who normally avoided eye contact were leaning in, laughing and actually asking to do math. It was a small change at first, but it began breaking down the anxiety that had been holding students back.

Their anxiety turns into curiosity, and their avoidance shifts into active participation. Students knew they could make mistakes, try again and keep moving without the fear of failure they often carried into traditional lessons.

Over time, I’ve learned that these games weren’t just fun. They were powerful teaching tools. Game-based learning platforms helped students review after new lessons and revisit older concepts to keep their skills sharp. As a result, when we moved on to fractions or multi-step problems, they weren’t burdened by forgotten fundamentals.

Now, I incorporate game-based learning throughout my curriculum. I may introduce a new lesson with a quick round or have students partner up to practice and reinforce a concept. Before a test, I can assign relevant game modules that give students a low-stakes way to practice and prepare.

I noticed students catching up quicker than in previous years. At the start of one school year, I had eight students who were pulled out of my class for extra math help. By the end of the year, only two needed the extra support.

And let’s be honest: These tools have helped me, too. Teaching math can be overwhelming, especially with constant pressure to get every student up to speed and prepared for benchmark tests.

Game-based learning became a comforting resource for me because it offers new ways to personalize lessons and celebrate small wins. As students play, I can track their learning in real time to see which skills they’ve mastered, where they’re struggling and how their performance is shifting over time. Students can move at their own pace now, and I can step into the role of guide rather than taskmaster.

Like any classroom tool, game-based learning works best when you use it with intention. Over the years, I’ve learned some strategies that make it more than just “play time.”

- Play along: When I first started using game-based learning platforms, I didn’t fully understand how each game worked or the way they built in rewards, challenges, and storylines that keep kids engaged.

That changed when I created my own character and began playing alongside my students. Suddenly, when a student shouted, “I just beat the Puppet Master!” I knew exactly what that meant, and I could celebrate and learn with them.

By experiencing the games myself, I learned how to implement them in the classroom. I could see firsthand how to weave them into lessons, when to use them for review versus pre-teaching, and how to keep the fun from becoming a distraction.

- Assign with purpose: I don’t just let students log in and click around. I strategically tie games to the key concepts we’re learning that week or use them to revisit skills. For example, I might assign a short warm-up where they tackle problems from earlier in the year so they’re never losing touch with old material. Cyclical practice helps build long-term retention while lowering the stress of new concepts.

- Differentiate lessons: One of the biggest wins with game-based learning is how easy it is to differentiate and personalize learning. In any classroom, I have students at wildly different levels: Some need extra review, others are ready to race ahead. With games, I can assign work that meets each child where they are.

That flexibility saves me time, but more importantly, it saves students from unnecessary stress. They can master concepts step by step, and I can gently move them up without overwhelming them.

When I first introduced game-based learning, I didn’t know what to expect. It felt like one more thing to manage. But I let students guide me, and the results spoke for themselves. They were more engaged, less anxious and more willing to try.

For teachers who are unsure, my advice is simple: Give it a chance. Watch your students light up when math feels less like a hurdle and more like a game. For me, the greatest reward has been seeing kids who once dreaded math start to relax, build confidence and move from “I can’t do this” to “Can we play again?”

Game-based learning isn’t about replacing rigor. It’s about sparking curiosity, reducing fear and creating the kind of engagement that fosters a genuine love of learning. Most of all, it reminds us — and our students — that math can, and should, be fun.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how