How well did you keep up with this week’s developments in K-12 education? To find out, take our five-question quiz below. Then, share your score by tagging us on social media with #K12DivePopQuiz.

How well did you keep up with this week’s developments in K-12 education? To find out, take our five-question quiz below. Then, share your score by tagging us on social media with #K12DivePopQuiz.

Principals from K-12 schools across the country traveled to Seattle to attend UNITED, the National Conference on School Leadership, July 11-13, where they discussed and shared solutions for the many challenges facing the education sector.

From concerns over school safety to the dilemma of chronic absenteeism, school leaders heard about innovative ways to tackle these issues by embracing local partnerships or looking into resources from national organizations.

Principals also learned about creative approaches emerging in the classroom. At one Indiana high school, for example, a public relations class is helping both to boost the school’s messaging to its community and to build students’ media skills. District administrators at Portland Public Schools, meanwhile, discussed how they’ve navigated and sustained a high-impact tutoring program in the state’s largest school district.

Read on for K-12 Dive’s coverage of the 2025 annual combined meeting of the National Association of Elementary School Principals and the National Association of Secondary School Principals.

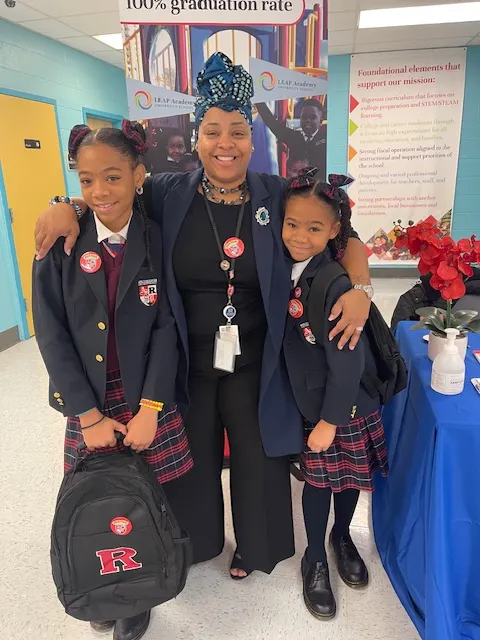

At LEAP Academy University School — a K-12 public charter school in Camden, N.J. — parents are required to volunteer at the school for 40 hours over the academic year.

School officials say volunteer engagement builds strong home-school connections and helps LEAP — which stands for Leadership, Education and Partnership — better understand and respond to parents’ needs. Parents, meanwhile, say volunteering gives them more voice and authority in school activities and helps build trust among the school community.

“The child sees that the parent trusts the school, and the parent is learning from the school and getting resources from the school,” says Cheree Coleman, a parent of rising 8th and 9th graders. “So now the student looks at the school like, ‘This is family. This is a place that I can go if I can’t get help from my parents or, you know, other resources.’ It’s stability.”

The school works with families to try to ensure the 40-hour requirement is not burdensome. Maria Cruz, director of LEAP’s Parent Engagement Center, says school leaders work with each family to find ways for them to help out within their own schedules or situations. Students’ relatives can also contribute to the families’ volunteer hours.

Volunteer hours can be gained by participating in any event at the 1,560-student school, including reading to students, planning special events, fundraising, attending parent workshops, serving on committees, sending emails to school groups, or any other activity that supports school efforts.

Cruz adds that while the school tracks the volunteer hours, no student would lose their spot if their family failed to meet the 40 hours.

“We work with them” to fill the hours, Cruz says. “We don’t tell them that the volunteer hours are mandatory. The word ‘mandatory’ is kind of like a negative term for them, so we don’t use it. We talk to them, let them know that the reason why we’re doing the volunteer hours is so they can be engaged in the school.”

The school, founded in 1997, has a long history of parent engagement, says Stephanie Weaver-Rogers, LEAP’s chief operation officer. “We opened based on parent needs so parents have always been integral and we are very focused on having parents involved in every aspect of the school.”

Parents attend a workshop on special education topics at LEAP Academy University School in Camden, N.J. in May 2025.

Permission granted by LEAP Academy University School

In addition to volunteering, the school engages parents through workshops specifically for them. Held weekly at the school, these optional parent workshops offer learning on a variety of topics and skills, such as homeownership, English language, employment, nutrition and technology.

Along with the free classes, parents get dinner, child care and parking also at no charge, Cruz says. She and other school staff work to recruit experts in the community — including other parents — to lead the classes.

The skills-based classes help parents “move forward” in their lives “and also help them better themselves for their children,” Weaver-Rogers says.

To further parent engagement efforts, the school encourages parents to apply for open positions, but Cruz noted that hires are made based on skills, experience and job fit. Currently, approximately 10-15% of LEAP staff are parents of current or former students.

Having parents on staff has several benefits, Weaver-Rogers said. It can give parents “a step up economically.” Plus, students behave better knowing their parents or their friends’ parents are in the building.

“It’s an all-around win,” Weaver-Rogers says.

Cheree Coleman and her daughters Cy’Lah Coleman (left) and Ca’Layla Coleman attend a school ceremony on May 29, 2024, at LEAP Academy University School in Camden, N.J.

Permission granted by Cheree Coleman

Coleman, who worked at the school as a parent ambassador for three years, adds, “What I love the most when it comes to the parent engagement with LEAP Academy is the fact that they don’t just educate the student, they educate the parents as well.”

The home-school connections at LEAP don’t end at graduation. The school, which has four buildings within two blocks, makes efforts to stay in touch with and support alumni through job awareness efforts, networking opportunities and resources for struggling families.

Coleman says LEAP staff and families have also supported students and families in need at other schools in the community.

The school opens its doors to the public for certain school events and celebrations — for instance, with community organizations and government service providers setting up information tables, Cruz says.

Hector Nieves, a member of the school’s board of trustees and chair of the parent affairs committee, says parents are encouraged to bring friends, neighbors and family to some school get-togethers, especially those held outside to accommodate larger crowds. “We have music. We have all kinds of games for the kids. There’s dancing,” he says.

Cruz added that this “all are welcome” approach helps the school recruit new students, too.

The whole school community participates in LEAP Academy University School’s holiday fundraiser, last held Dec. 5-14, 2024, at the school in Camden, N.J.

Permission granted by LEAP Academy University School

Additionally, LEAP’s partnership with Rutgers University provides support to families for their children from birth through postsecondary education. LEAP is located along Camden’s “Education Corridor,” which includes campuses for Rutgers University-Camden and Rowan University. Both Rutgers and Rowan provide dual enrollment, early college access and other learning opportunities for LEAP students.

Nieves, who had three children graduate from LEAP — including one who now teaches English at the school — says the holistic approach of serving students and families has empowered the school community over the years and helped families improve their financial situations.

“I believe that somehow, whether they came and worked here, we gave them classes, we helped them along, all of a sudden, I see this growth,” says Nieves. “I believe we had a lot to do with that.”

Many of the Justice Department’s allegations against UCLA stem from a pro-Palestinian encampment erected on its campus in the spring 2024 term.

University leaders allowed the encampment to remain for nearly a week, citing a need to balance safety with free speech protections. They ultimately asked the Los Angeles Police Department to clear the encampment following a violent night in which counterprotesters attempted to tear down the encampment’s barricades, launched fireworks into it and hit pro-Palestinian demonstrators with sticks and other objects.

The pro-Palestinian protesters at times fought back, though video footage from the night shows few instances of them initiating confrontations, according to reporting from The New York Times. When police arrived — hours after violence first broke out — they didn’t step in immediately.

According to the Justice Department, at least 11 complaints were filed with UCLA alleging that students experienced discrimination based on race, religion or national origin from encampment protesters.

The agency also cited a UCLA task force report that found some encampment protesters formed human blockades to stop people — including students wearing the Star of David or those who refused to denounce Zionism — from freely moving throughout Royce Quad.

Milliken noted in his statement that UCLA has taken several steps since then to tighten campus protest policies and combat antisemitism. The university instituted a systemwide ban on encampments and launched a campus initiative in March to fight antisemitism, including through training and an improved system for handling complaints.

UCLA also agreed last month to pay $6 million to settle a lawsuit brought by three Jewish students and a Jewish professor who alleged the university violated their civil rights by allowing the encampment protesters to impede their access to the campus. Over one-third of the settlement payment will go toward organizations that fight antisemitism, The Associated Press reported.

Meanwhile, the university is facing a separate lawsuit brought by about three dozen pro-Palestinian students, faculty and others who allege that UCLA’s leaders didn’t protect them from the counterprotesters and failed to uphold their right to free expression. The lawsuit also names the counterprotesters as defendants.

Their lawsuit says UCLA police merely “stood and watched” for hours while counterprotesters “ruthlessly attacked” the encampment demonstrators, alleging the group broke their bones, burned their eyes with chemicals, and hit them with metal rods and other weapons.

The next day, the LAPD and the California Highway Patrol cleared the encampment at the request of university leaders. According to the lawsuit, law enforcement “hurled flashbangs, shot powerful kinetic impact projectiles at peoples’ heads and faces, and used excessive physical force against and falsely arrested students, faculty, and concerned community members.”

Police arrested over 200 people while clearing the encampment. Those detained faced “invasive searches, false arrests, sexual assaults, and prolonged detentions,” and hijab-wearers were forced to remove their head coverings “infringing on their religious practices,” the lawsuit alleged.

The pro-Palestinian plaintiffs suing UCLA are seeking damages and for the judge to declare the clearing of the encampment illegal, among other measures.

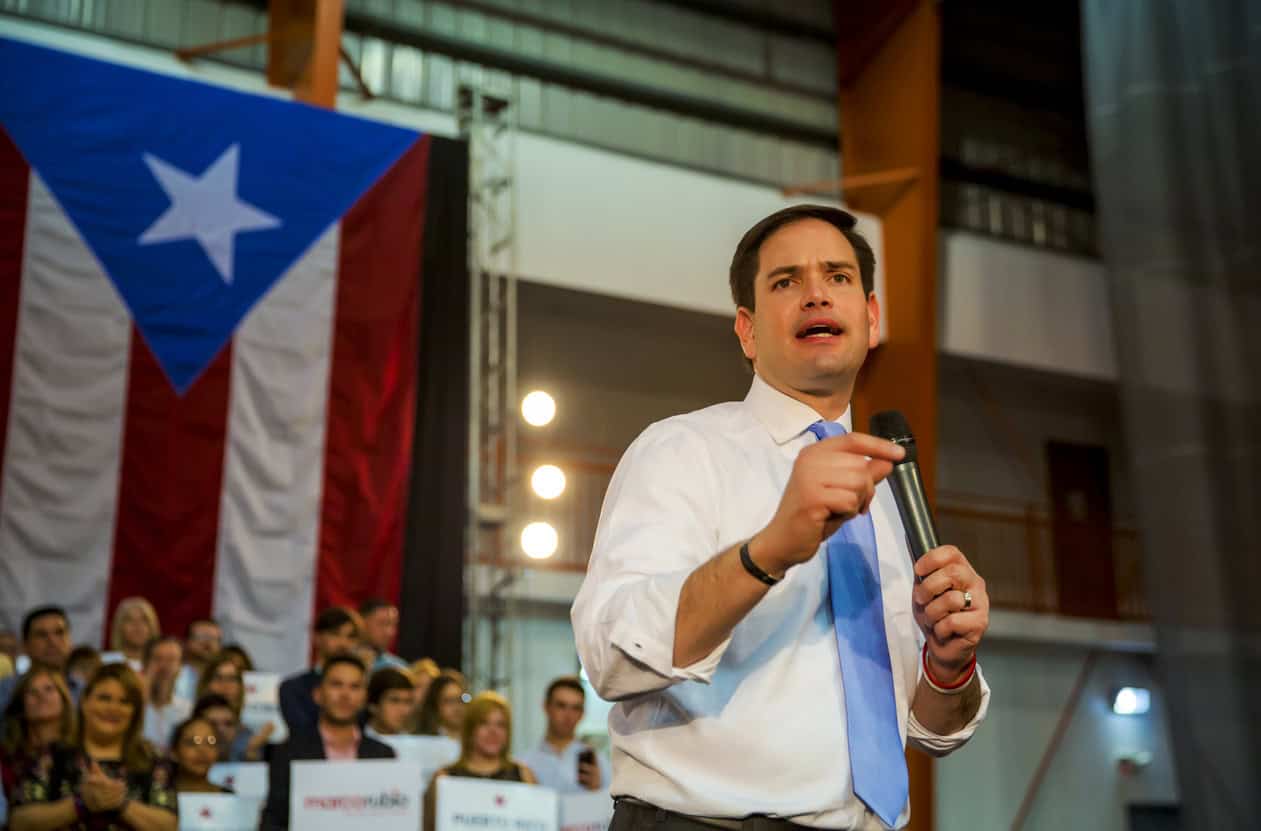

The legal challenge takes aim at Rubio’s use of statutes to deport legal noncitizens, namely international students Mahmoud Khalil and Rümeysa Öztürk, for their speech alone. It was filed by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) on August 6.

“In the United States of America, no one should fear a midnight knock on the door for voicing the wrong opinion,” said FIRE attorney Conor Fitzpatrick: “Free speech isn’t a privilege the government hands out. Under our constitution it is the inalienable right of every man, woman and child.”

FIRE, a non-partisan advocacy group, is seeking a landmark ruling that the first amendment trumps the statutes that the government used to deport international students and other lawfully present noncitizens for protected speech earlier this year.

It cites the case of Mahmoud Khalil, an international student targeted by the Trump administration for his pro-Palestinian activism, who was held in detention for three months after being arrested by plain clothed immigration officers in a Columbia University building.

The complaint also highlights the targeting of Tufts University student Rümeysa Öztürk, detained on the street and held for nearly seven weeks for co-authoring an op-ed calling for Tufts to acknowledge Israel’s attacks on Palestine and divest from companies with ties to Israel.

FIRE has said that that Rubio and Trump’s targeting of international students is “casting a pall of fear over millions of noncitizens, who now worry that voicing the ‘wrong’ opinion about America or Israel will result in deportation”.

This spring, thousands of students saw their visas revoked by the administration, after a speech from Rubio warning them: “We give you a visa to come and study to get a degree, not to become a social activist that tears up our university campuses”.

Free speech isn’t a privilege the government hands out

Conor Fitzpatrick, FIRE

Though the students’ statuses have since been restored following a court hearing deeming the mass terminations to be illegal, some students opted to leave the US amid fears of being detained or deported.

This summer, international student interest in the US fell to its lowest level since mid-pandemic, with new estimates forecasting a potential 30-40% decline in new international enrolments this fall following the state department’s suspension of new visa interviews.

Plaintiffs in the lawsuit include The Stanford Daily – the independent, student newspaper at Stanford University – and two legal noncitizens with no criminal record who fear deportation and visa revocation for engaging in pro-Palestinian speech.

“There’s real fear on campus and it reaches into the newsroom,” said Greta Reich, editor-in-chief of The Stanford Daily.

“I’ve had reporters turn down assignments, request the removal of some of their articles, and even quit the paper because they fear deportation for being associated with speaking on political topics, even in a journalistic capacity.

“The Daily is losing the voices of a significant portion of our student population,” said Reich.

The complaint argues that Rubio’s wielding of two provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act is unconstitutional when used to revoke a visa or deport someone for the first amendment right of free speech.

“The first allows the secretary of state to render a noncitizen deportable if he ‘personally determines’ their lawful ‘beliefs, statements, or associations’ ‘compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest’”, explains the document.

“The second allows the secretary ‘at any time, in his discretion, revoke’ a ‘visa or other documentation’”.

The complaint argues that both provisions are unconstitutional as applied to protected speech, based on the first amendment promise “that the government may not subject a speaker to disfavoured treatment because those in power do not like his or her message”.

In our free country, you shouldn’t have to show your papers to speak your mind

Will Creeley, FIRE

According to the claimants, Trump and Rubio’s targeting of international students is evidence of noncitizens not being afforded the same free speech protections as US nationals, which, they say, runs against America’s founding principles.

“Every person – whether they’re a US citizen, are visiting for the week, or are here on a student visa – has free speech rights in this country,” said FIRE.

“Two lawful residents of the United States holding the same sign at the same protest shouldn’t be treated differently just because one’s here on a visa,” said FIRE legal director Will Creeley.

“The First Amendment bars the government from punishing protected speech – period. In our free country, you shouldn’t have to show your papers to speak your mind.”

The lawsuit comes amid heightened scrutiny of international students in the US, with the state department ordering consular officers to ramp up social media screening procedures.

As of June 2025, US missions abroad will now vet students for instances of “advocacy for, aid, or support of foreign terrorists and other threats to US national security,” as well as any signs of “anti-Semitic harassment and violence” among applicants.

The NIH is one of several agencies where a political appointee will have to sign off on grant awards.

Wesley Lapointe/The Washington Post via Getty Images

President Donald Trump is now requiring grant-making agencies to appoint senior officials who will review new funding opportunity announcements and grants to ensure that “they are consistent with agency priorities and the national interest,” according to an executive order issued Thursday. And until those political appointees are in place, agencies won’t be able to make announcements about new funding opportunities.

The changes are aimed at both improving the process of federal grant making and “ending offensive waste of tax dollars,” according to the order, which detailed multiple perceived issues with how grant-making bodies operate.

The Trump administration said some of those offenses have included agencies granting funding for the development of “transgender-sexual-education” programs and “free services to illegal immigrants” that it claims worsened the “border crisis.” The order also claimed that the government has “paid insufficient attention” to the efficacy of research projects—noting instances of data falsification—and that a “substantial portion” of grants that fund university-led research “goes not to scientific project applicants or groundbreaking research, but to university facilities and administrative costs,” which are commonly referred to as indirect costs.

It’s the latest move by the Trump administration to take control of federally funded research supported by agencies such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy. Since taking office in January, those and other agencies have terminated thousands of grants that no longer align with their priorities, including projects focused on vaccine hesitancy, combating misinformation, LGBTQ+ health and promoting diversity, equity and inclusion.

Federal judges have since ruled some of those terminations unlawful. Despite those rulings, Thursday’s executive order forbids new funding for some of the same research topics the administration has already targeted.

It instructs the new political appointees of grant-making agencies to “use their independent judgment” when deciding which projects get funded so long as they “demonstrably advance the president’s policy priorities.”

Those priorities include not awarding grants to “fund, promote, encourage, subsidize, or facilitate” the following:

The order also instructs senior appointees to give preference to applications from institutions with lower indirect cost rates. (Numerous agencies have also moved to cap indirect research cost rates for universities at 15 percent, but federal courts have blocked those efforts for now.)

Families reportedly spent an average of $30,837 for college last year.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images | Rawpixel

Families are spending about 9 percent more on college compared to last year, according to a recently released survey from Sallie Mae and Ipsos.

The results of the survey, released earlier this week, are part of the annual “How America Pays for College” report. Ipsos surveyed about 1,000 undergraduate students and the same number of parents of undergrads from April 8 to May 8. The online survey delved into a range of topics from how they were paying for college to their views on the federal student loan program.

On average, families spent $30,837 on college, which is similar to pre-pandemic spending—in the 2019–20 academic year, families spent $30,017 on average. In line with previous years, families are typically using their own money to pay for college, with income and savings adding up to 48 percent of the pie, and scholarships and grants accounted for a 27 percent slice.

But 40 percent of the families surveyed didn’t seek scholarships to help pay for college because they either didn’t know about the available opportunities or didn’t think they could win one. About three-quarters of respondents who received a scholarship credited that aid with making college possible.

Similar to other recent surveys, while a majority of families see college as worth the money, cost is still a key factor. About 79 percent reported that they eliminated at least one institution based on the price tag. Still, about 47 percent of respondents said they ended up paying less than the sticker price. That number is higher for families with students at private four-year universities. About 54 percent said they paid less compared to 45 percent of respondents at public four-year institutions.

The Education Department’s yearlong effort to roll out the sweeping higher ed changes signed into law last month kicked off Thursday with a four-hour hearing that highlighted the many tweaks college administrators and others want to see.

The law, known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, capped federal student loans, created new loan-repayment plans, extended the Pell Grant to include short-term workforce programs and instituted a new measure to hold institutions accountable. Now, the department is planning to propose and issue new regulations that spell out how those various changes will work.

On nearly all fronts, college administrators, policy experts and students argued that lawmakers left significant gaps in the legislation, and they want a say in how Trump administration officials fill them in. For instance, the legislation doesn’t explain what data will be collected for either workforce Pell or the accountability measure or who will have to take on that task. Some speakers raised concerns about how new reporting requirements could increase administrative burdens for colleges.

But Nicholas Kent, the department’s newly confirmed under secretary, said at the start of the meeting that he looks forward to clarifying all the details during the lengthy process known as negotiated rule making.

“Simply put, the current approach to paying for college is unsustainable for both borrowers and for taxpayers,” Kent said. “President Trump has laid out a bold vision, one that aims to disrupt a broken system and return accountability, affordability and quality to postsecondary education that includes reducing the cost of higher education, aligning program offerings with employer needs [and] embracing innovative education models … Today’s public hearing marks a key milestone in our accelerated timeline to implement this sweeping legislative reform.”

Neither Kent nor other department officials said what specific changes and clarifications are on the table.

Negotiated rule making, or “neg-reg,” started in the early 1990s. It entails using an advisory committee to consider and discuss issues with the goal of reaching consensus in developing a proposed rule. Consensus means unanimous agreement among the committee members, unless the group agrees on a different definition. The department must undertake negotiated rule making for any rule related to federal student aid.

Determining the details of the regulations and policy changes will be left up to two committees of higher education leaders, policy experts and industry representatives that will review and negotiate over the department’s proposals during a series of meetings throughout the fall and into the new year. The first committee is scheduled to begin discussions in September.

In the meantime, here are three key issues Thursday’s speakers said they hope to see addressed by both the advising panels and department officials before the legislation starts taking effect in July 2026.

Before the public hearing, some higher ed lobbyists and advocates raised concerns about who would be included on the advisory committees. Multiple constituent groups argued they weren’t properly represented on the committees.

For instance, neither committee includes a representative from the financial aid community, despite the fact that college financial aid administrators will play a key role in implementing the legislation on campuses.

Multiple groups, including the American Council on Education, drew attention to the absence, but Melanie Storey, president of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, voiced the most concern.

Financial aid professionals will “interpret, communicate and operationalize the intricate details of this wide-ranging bill for millions of students and families. To exclude their practical, technical experience from the negotiation table risks developing rules that are difficult to administer, creating unintended negative consequences,” she said. “We have heard the perspective that representatives from each college sector can speak to the needs of their institutions. However, their role is to advocate for the broad interests of that sector. That is fundamentally different from representing the profession responsible for the … mechanics of aid delivery.

A department official who moderated the hearing, responded, “We expect we will have financial aid administrators at the table,” as the department has in the past, but he did not clarify how that would be done. (This paragraph has been corrected.)

Other speakers called for better representation of civil rights advocates, apprenticeship program leaders and minority-serving institutions, but none of those requests were directly addressed by government officials.

Speakers also raised questions about how the new caps to student loans would work and whom they would affect.

As part of negotiated rule making, the Education Department must:

Congress’s Big Beautiful Bill caps loans for professional degrees at $200,000 and limits loans for graduate programs to half of that. But lawmakers didn’t specify which degree programs fall in which category. Determining how to sort programs will likely be a key point of debate for the rule-making committee, the comments showed.

Certain programs, like law and medical school, will almost certainly be considered professional programs, but other programs, like master’s degrees in nursing, education or social work, are not guaranteed. Knowing this, a variety of academic association representatives, workforce advocates and college administrators made their case throughout the hearing for why their own discipline should be a professional program.

Matt Hooper, vice president of communications for the Council on Social Work Education, said to not include certain programs in the professional bucket would mean ignoring their critical nature as a public service.

Social work graduates “pursue careers in health care, children and family services, criminal justice, public policy, government, and more,” he said. “An M.S.W. provides full professional preparation, similar to a J.D. in law or an M.D. in medicine, and we think it should be categorized in the same respect.”

A handful of speakers went so far as to argue that certain bachelor’s programs, like aviation or aeronautical science, that are often paired with certification from the Federal Aviation Administration should be grouped into the professional category, as they come at a cost and time commitment similar to graduate school.

If those programs don’t get the benefit of a higher loan cap, multiple airline advocates said, America could see a steep shortage of pilots within the next two decades.

“Over the next 15 years, nearly half of our nation’s airline pilots will retire due to mandatory age limits,” said Sharon DeVivo, president of Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology. “The current training pipeline is not equipped to meet that demand, putting at risk the transportation infrastructure, especially the economic health of small and rural communities that depend on reliable air service.”

Training to become a pilot can cost $80,000 to $100,000 more than a traditional bachelor’s degree, added Carlos Zendejas, vice president of flight operations at the regional airline Horizon Air. So to hold these students to the same loan limit as other undergraduates would deter prospective pilots from pursuing a high-return-on-investment career.

“The need to stabilize the pilot pipeline is real,” he said. “The One Big Beautiful Bill gives the department the ability to fix this.”

Since the inauguration, Trump officials in all sectors of the federal government have been vocal about combating fraud, waste and abuse. But higher education experts are concerned that one measure in the reconciliation bill could do the opposite.

The new accountability tool it introduced uses a new earnings test to evaluate colleges’ eligibility for federal student loans. But it does not apply to certificate programs, which some policy and data analysts say are more likely to provide a poor return on investment.

According to a recent report from the Postsecondary Education and Economics Research Center at American University, only 1 percent of college programs at the associate level and higher will fail the new earnings test, but about 19 percent of certificate programs would do so.

Representatives from American as well as New America, Third Way and the Century Foundation, all progressive think tanks, sounded the alarm on the matter at Thursday’s hearing. As a solution, they encouraged the administration to keep an existing accountability policy in place that applies to certificate programs and for-profit institutions. That metric, known as the gainful-employment rule, is not codified in law.

“A recent publication from the Senate health committee’s chairman, Bill Cassidy, confirms it was not lawmakers’ intent to exempt such programs from any accountability,” said Clare McCann, the PEER Center’s managing director of policy and operations. “So to carry out that intent, the department should maintain a strong gainful-employment program regulation for those programs that should include maintaining the debt-to-earnings tests under the gainful-employment rules, which are an important check on institutions offering unaffordable degrees.”

Jonathan Brown, the Alwaleed bin Talal Chair of Islamic Civilization at Georgetown University, was suspended from his job and is being investigated for posting on X after the US bombing of Iran, “I hope Iran does some symbolic strike on a base, then everyone stops.” Brown’s expressed desire for peace was twisted by conservatives into some kind of anti-American call for violence.

Rep. Randy Fine, a Florida Republican, noted that the interim president of Georgetown would soon be testifying before Congress and wrote about Brown, “This demon had better be gone by then. We have a Muslim problem in America.” Fine was Gov. Ron DeSantis’s choice to be president of Florida Atlantic University before the board rejected him. But his literal demonization of speech has a powerful impact.

Georgetown quickly obeyed the commands of anti-Muslim bigots such as Fine. Georgetown interim president Robert M. Groves testified to Congress on July 15, “Within minutes of our learning of that tweet, the dean contacted Professor Brown, the tweet was removed, we issued a statement condemning the tweet, Professor Brown is no longer chair of his department and he’s on leave, and we’re beginning a process of reviewing the case.”

Groves responded “yes” when asked by Rep. Virginia Foxx, a North Carolina Republican, “You are now investigating and disciplining him?”

Georgetown’s statement declared, “We are appalled that a faculty member would call for a ‘symbolic strike’ on a military base in a social media post.” But why would this appall anyone? Faculty members routinely support actions that actually kill innocent people—tens of thousands of people, in the case of professors who support Israel’s attack on Gaza, millions of people in the case of professors who supported the fight against the Nazis in World War II. And that’s all perfectly legitimate. So a professor calling for an action against a military target that doesn’t kill anybody should be the most trivial statement in the world.

There is a good reason why universities shouldn’t take positions on foreign policy—because institutional opinions are often dumb, especially when formulated “within minutes” rather than after serious thought. Georgetown is making the worst kind of violation of institutional neutrality—not merely expressing a dumb opinion, not just denouncing a professor for disagreeing with that dumb opinion, but actually suspending a professor for diverging from Georgetown’s very dumb official opinion on foreign policy.

Often, defenders of academic freedom have to stand for this principle even when addressing terrible people who say terrible things. But the assault on academic freedom in America has become so awful that even perfectly reasonable comments are now grounds for automatic suspension. Brown’s position on the Iran attacks is very similar to that of Donald Trump, who posted praise for Iran after it did precisely what Brown had urged: “I want to thank Iran for giving us early notice, which made it possible for no lives to be lost, and nobody to be injured.” Unlike Trump, Brown never thanked Iran for attacking a U.S. base. So how could any university even consider punishing a professor for taking a foreign policy stand more moderate than Trump?

Georgetown’s shocking attacks on academic freedom have garnered little attention or criticism. The Georgetown Hoya reported in a headline, “Groves Appears to Assuage Republicans, Defend Free Speech in Congressional Hearing.”

The newspaper’s fawning treatment of Groves as a defender of free speech apparently was based on Groves testifying, “We police carefully the behavior of our faculty in the classroom and their research activities,” and adding, “They are free, as all residents of the United States, to have speech in the public domain.” It’s horrifying to have any university president openly confess that they “police carefully” professors’ teaching and research. But for Groves to claim that faculty have free speech “in the public domain” when he proudly suspended Brown for his comments must be some kind of sick joke.

Another Hoya headline about the controversy declared, “University Review of GU Professor for Controversial Posts Prompts Criticism, Praise.” While the campus Students for Justice in Palestine and the Council on American-Islamic Relations correctly defended Brown, the Anti-Defamation League declared, “We commend Georgetown University for taking swift action following Jonathan Brown’s dangerous remarks about a ‘symbolic strike’ on a U.S. military base.”

There is nothing “dangerous” about Brown’s remarks calling for an end to war, or any other foreign policy opinions. The only danger here is the threat to academic freedom.

When Georgetown suspended lecturer Ilya Shapiro in 2022 for his offensive comments on Twitter, I argued that “Shapiro should not be punished before he receives a hearing and fair evaluation” and added, “A suspension, even with pay, is a form of punishment. In fact, it’s a very harsh penalty when most forms of campus misconduct receive a reprimand or a requirement for education or changes in behavior.”

I called upon all colleges to ban the use of suspensions without due process. Since then, suspensions have become an epidemic of repression on college campuses. An army of advocates once argued in defense of Shapiro’s free speech. Unfortunately, none of Shapiro’s outspoken supporters have spoken out with similar outrage about the even worse treatment of Brown by Georgetown’s censors.

Georgetown’s administrators must immediately rescind Brown’s ridiculous suspension, restore his position as department chair, end this unjustified investigation of his opinions, apologize for their incompetence at failing to meet their basic responsibilities to protect academic freedom and enact new policies to end the practice of using arbitrary suspensions without due process as a political weapon.