Last year, FIRE launched the Free Speech Dispatch, a regular series covering new and continuing censorship trends and challenges around the world. Our goal is to help readers better understand the global context of free expression. Want to make sure you don’t miss an update? Sign up for our newsletter.

Five arrests over cartoon “publicly demeaning religious values”

Cartoons depicting Muhammad are a common feature in censorship news but the latest developments out of Turkey are a little unusual in that the magazine involved is adamant that the cartoon under fire…does not actually depict the prophet.

On June 30, Turkish police arrested four employees of satirical magazine LeMan on charges of “publicly demeaning religious values,” with one cartoonist also charged with “insulting the president.” They raided the magazine’s office as well and, two weeks later, arrested a LeMan editor at Istanbul’s airport upon his return from France. The arrests followed an attack on the LeMan office, with a mob breaking open windows and doors.

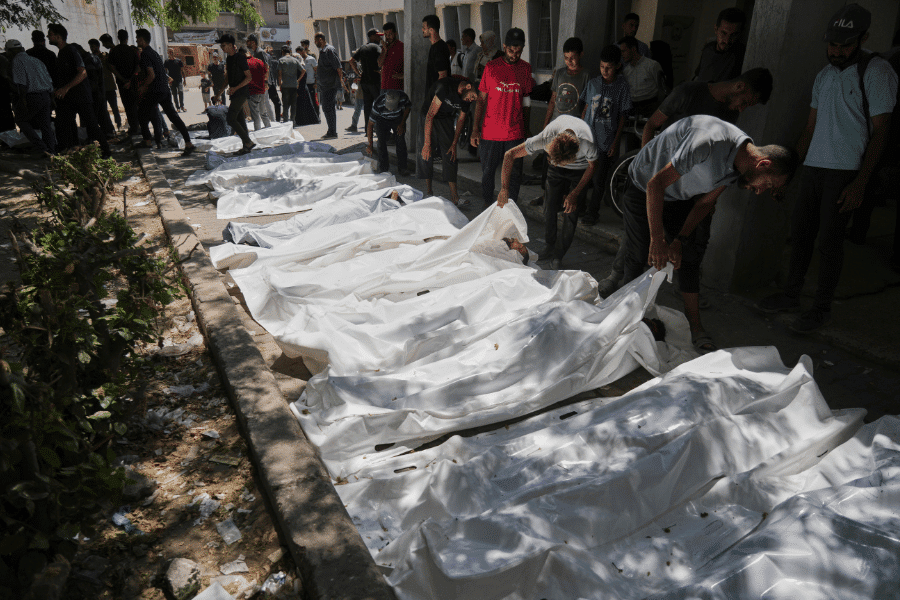

The origin of the dispute? A June 26 LeMan edition with an anti-war cartoon depicting two winged men — one depicted as Muslim and introducing himself as Muhammad and the other as Jewish and calling himself Moses — shaking hands as they ascend over a burning city with bombs raining down. The Muhammad character, the magazine said, “is fictionalised as a Muslim killed in Israel’s bombardments” and is named so because it’s the “most commonly given and populous name in the world.”

The magazine remains adamant its staff is being arrested on the basis of a willful misunderstanding, but for now Turkish officials — including President Erdogan, who called it a “vile provocation” that must be “held accountable before the law” — are intent on prosecution and have seized copies of the edition.

There’s more free speech news out of Turkey. A new law granted the country’s Presidency of Religious Affairs the authority to ban Quran translations it deems “do not correspond to the basic characteristics of Islam,” including online and audio versions. Meanwhile, a Turkish court blocked some content produced by xAI’s Grok for insulting Erdogan and religious values.

And Spotify has threatened to leave the Turkish market in part over a censorship dispute with the deputy minister of culture and tourism, who has accused the site of hosting “content that targets our religious and national values and insults the beliefs of our society.” That content apparently includes playlists like “The songs Emine Erdogan listens to while cleaning the palace,” which mocks Erdogan’s wife’s allegedly lavish spending.

UK’s free speech controversies online and off — and in American visa policy

The UK’s free speech issues are nothing new, but this time the U.S. is part of the story, too. UK prosecutors had already announced an investigation into Belfast rap trio Kneecap earlier this year — which, as of last week, has been dropped — but now duo Bob Vylan is on the list.

Bob Vylan caught global attention last month in a controversial Glastonbury set which included a “Death, death to the IDF” chant led by the band. Avon and Somerset Police confirmed they were reviewing footage to confirm “whether any offences may have been committed that would require a criminal investigation.” Prime Minister Keir Starmer also objected to the “appalling hate speech” and demanded answers from the BBC about its broadcast of the set. Shadow Home Secretary Chris Philp also said the BBC “appears to have also broken the law.”

Then the Trump administration joined in. Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau announced shortly after the incident that the U.S. revoked the visa of Bob Vylan members ahead of the band’s upcoming tour. “Foreigners who glorify violence and hatred are not welcome visitors to our country,” he wrote.

Speech controversies also bloomed outside Glastonbury. UK police have now arrested dozens of demonstrators for attending events opposing the ban on Palestine Action, an activist group restricted under British anti-terrorism legislation for damaging military planes in a protest. Simply “expressing support” for the banned group is a crime.

The Wall Street Journal covered the UK’s (and Europe’s) “far and wide” crackdown on speech in a July 7 piece that also discussed the recent targeting of activist Peter Tatchell, arrested by police in London for a “racially and religiously aggravated breach of the peace.” Tatchell’s offense was holding a sign “that criticized Israel for its Gaza campaign as well as Hamas for kidnapping, torturing and executing a 22-year-old.”

Also, in more unsurprising news, the UK’s troubling Online Safety Act is making its mark on the internet as social media platforms begin the process of age verification for UK-based users. Bluesky users will be required to use Kid Web Services or face content blocks and app limitations. Reddit users must verify too, or lose access to categories of material including “content that promotes or romanticizes depression, hopelessness and despair” and “content that promotes violence.”

And, finally, is the UK getting a government-imposed swear jar? A district council in Kent is considering a £100 fine for swearing in public. That definitely won’t backfire.

Fake news, social media for teens, and more in the latest tech and speech developments

- Last week, Russian legislators passed rules issuing fines for people who “deliberately searched for knowingly extremist materials,” with heightened fines for those using a VPN to access them. That’s not just censorship of what you say, but also of what you simply try to see.

- The European Court of Human Rights ruled in Google’s favor in its dispute with Russia over penalties the government issued against the company over its decision not to remove some political content and to suspend a channel tied to sanctions. Russia, it found, “exerted considerable pressure on Google LLC to censor content on YouTube, thereby interfering with its role as a provider of a platform for the free exchange of ideas and information.”

- The Indian state of Karnataka is considering legislation that would punish fake news, misinformation, and other verboten forms of speech with fines and prison terms up to seven years.

- India’s Allahabad High Court refused bail to a man who had posted “heavily edited and objectionable” videos of Prime Minister Modi relating to the country’s recent conflict with Pakistan. “Freedom of speech and expression does not stretch to permit a person posting videos and other posts disrespecting the Prime Minister of India,” the court wrote.

- An 8-3 vote from Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that social media companies will be held liable for failure to monitor and remove “content involving hate speech, racism, and incitement to violence.”

- German police conducted a search of more than 65 properties in a crackdown on online hate speech, seeking out offenders allegedly engaged in “inciting hatred, insulting politicians and using symbols of terrorist groups or organizations that are considered to be unconstitutional.”

- Dozens of online gay erotica writers, mostly young women, have been arrested in recent months in China for “producing and distributing obscene material.”

- The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority has now blocked over 100,000 URLs across the internet for “blasphemous content.”

- An Australian Administrative Review Tribunal ruling reversed a March order by the country’s eSafety Commissioner requiring X to take down a post from Canadian activist Chris Elston or face a $782,500 fine. Elston had called Teddy Cook, a trans man appointed to a World Health Organization panel, a “woman” who “belong[s] in psychiatric wards.”

- New guidelines issued by the European Commission press for EU nations’ adoption of tools to verify internet users’ age to protect them against harmful content. The verification methods should be “accurate, reliable, robust, non-intrusive and non-discriminatory” — quite a Herculean feat to expect.

- China is introducing a new digital ID system transferring the possession of users’ identifying information away from internet companies and into government hands. The process, voluntary at this time, will require users to submit personal information, including a facial scan.

Former Panamanian president alleges U.S. visa revocation for his political speech

Martín Torrijos, a former president of Panama, says the U.S. canceled his visa over his opposition to political agreements made between the two countries. Torrijos suggested his signature on the “National Unity and Defense of Sovereignty” statement, which criticized “expansionist and hegemonic intentions” by the United States, also contributed to the revocation.

“I want to emphasize that this is not just about me, neither personally nor in my capacity as former president of the Republic,” Torrijos said. “It is a warning to all Panamanians: that criticism of the actions of the Government of Panama regarding its relations with the United States will not be tolerated.”

Free press news, from Azerbaijan to Arad

- Zimbabwe Independent editor Faith Zaba penned a satirical column about the country’s role in the Southern African Development Community — and was then arrested by police and charged with “undermining the authority of the president.”

- Yair Maayan, mayor of Israeli city Arad, announced he intended to ban the sale of Haaretz over the newspaper’s investigation into the IDF.

- Tel Aviv police arrested journalist Israel Frey on suspicion of incitement to terrorism for his response to the death of five IDF soldiers. “The world is a better place this morning, without five young men who partook in one of the most brutal crimes against humanity,” he posted on social media.

- The Baku Court of Serious Crimes sentenced seven staffers at Azerbaijani investigative outlet Abzas Media to prison terms ranging from seven to more than nine years on various tax and fraud charges. Press freedom advocates say the charges are in retaliation for the outlet’s reporting on presidential corruption.

- A German court overturned the ban on Alternative for Germany-linked magazine Compact, which Interior Minister Nancy Faeser had called “a central mouthpiece of the right-wing extremist scene.” The court found that the measure was not justified.

- The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s military arrested journalist Serge Sindani after he shared a photo showing military planes at Bangoka International Airport.

- At least two journalists were injured during recent protests in Kenya, where the country’s Communications Authority demanded “all television and radio stations to stop any live coverage of the demonstrations” or risk “regulatory action.”

- Police in Nepal are ignoring a court order and attempting to hunt down and arrest journalist Dil Bhushan Pathak for his reporting alleging political corruption.

Changes on the horizon in higher education abroad

New wide-ranging guidance from the UK’s Office for Students includes the recommendation that universities amend or terminate international partnerships and agreements if necessary to protect the speech rights of their community. This is welcome advice given global higher education’s failure to acknowledge and account for the challenges internationalization has posed to expressive rights, a problem I discuss in my forthcoming book Authoritarians in the Academy, out Aug. 19 and available for pre-order now.

And, like in the United States, universities in Australia are facing pressure over allegations of campus antisemitism. The nation’s Special Envoy’s Plan to Combat Antisemitism advocates various measures, including adoption of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition and its examples. Universities that “facilitate, enable or fail to act against antisemitism” may face defunding. (FIRE has repeatedly expressed concerns about these applications of the IHRA definition in the U.S. and the likelihood it will censor or chill protected political speech.) The report also advises that non-citizens, which would include international students, “involved in antisemitism should face visa cancellation and removal from Australia.”