This story is part of Hechinger’s ongoing coverage about rethinking high school. See our articles about a new diploma in Alabama and a “career education for all” model in Kentucky.

ELKHART, Ind. — Ever since Ty Zartman was little, people told him he had to go to college to be successful. “It was engraved on my brain,” he said.

But despite earning straight A’s, qualifying for the National Honor Society, being voted prom king and playing on the high school football and baseball teams, the teen never relished the idea of spending another four years in school. So in fall 2023 he signed up through his Elkhart, Indiana, high school for an apprenticeship at Hoosier Crane Service Company, eager to explore other paths. There, he was excited to meet coworkers who didn’t have a four-year degree but earned good money and were happy in their careers.

Through the youth apprenticeship, Ty started his day at the crane manufacturing and repair business at 6:30 a.m., working in customer service and taking safety and training courses while earning $13 an hour. Then, he spent the afternoon at his school, Jimtown High, in Advanced Placement English and U.S. government classes.

In June, the 18-year-old started full-time at Hoosier Crane as a field technician.

“College is important and I’m not dissing on that,” Ty said. “But it’s not necessarily something that you need.”

Elkhart County is at the forefront of a movement slowly spreading across Indiana and the nation to make apprenticeships a common offering in high school.

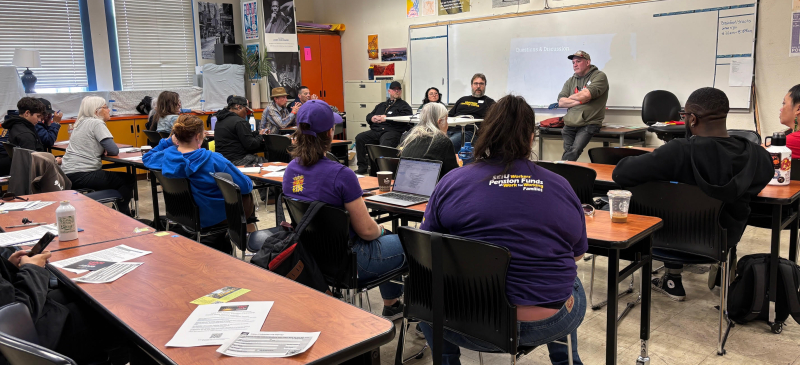

In 2019, as part of a plan to boost the region’s economic prospects, county leaders launched an effort to place high schoolers in apprenticeships that combine work-based training with classroom instruction. About 80 students from the county’s seven school districts participated this academic year, in fields such as health care, law, manufacturing, education and engineering. In April, as part of a broader push to revamp high school education and add more work-based learning, the state set a goal of 50,000 high school apprentices by 2034.

Tim Pletcher, the principal of Jimtown High, said students are often drawn first to the chance to spend less time in class. But his students quickly realize apprenticeships give them work-based learning credits and industry connections that help them after graduation. They also earn a paycheck. “It’s really causing us to have a paradigm shift in how we look at getting kids ready for the next step,” he said.

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

This “earn and learn” model is taking hold in part because of deepening disillusionment with four-year college, and the fact that well-paying jobs that don’t require bachelor’s degrees are going unfilled nationally. The past three presidential administrations invested in expanding apprenticeships, including those for high schoolers, and in April, President Donald Trump signed an executive order calling for 1 million new apprentices. In a recent poll, more than 80 percent of people said they supported expanding partnerships between schools and businesses to provide work-based learning experiences for students.

Yet in the United States, the number of so-called youth apprenticeships for high schoolers is still “infinitesimally small,” said Vinz Koller, a vice president at nonprofit group Jobs for the Future. One estimate suggests they number about 20,000 nationally, while there are some 17 million high school students. By contrast, in Switzerland — which has been praised widely for its apprenticeship model, including by U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon — 70 percent of high schoolers participate. Indiana is among several states, including Colorado, South Carolina and Washington, that have embraced the model and sent delegations to Switzerland to learn more.

Experts including Ursula Renold, professor of education systems at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, note that importing the model to the United States at a large scale won’t be simple. Most businesses aren’t accustomed to employing apprentices, parents can be resistant to their students trading four-year college aspirations for work, and public transportation to take students to apprenticeships is limited, especially in rural areas. Many high schoolers don’t have a driver’s license, access to a car or money for gas. School districts already face a shortage of bus drivers that makes transporting students to apprenticeships difficult or impossible.

Still, Renold, who is known as the “grande dame of apprenticeships,” said Indiana’s commitment to apprenticeships at the highest levels of state government, as well as the funding the state has invested in work-based learning, at least $67 million, seem to be setting the state up for success, though it could take a decade to see results.

“If I had to make a bet,” said Renold, “I would say it’s Indiana who will lead the way.”

Related: Apprenticeships are a trending alternative to college, but there’s a hitch

Elkhart County’s experiment with apprenticeships has its roots in the Great Recession. Recreational vehicle manufacturing dominates the local economy, and demand for the vehicles plummeted, contributing to a regional unemployment rate at that time of nearly 20 percent. Soon after, community leaders began discussing how to better insulate themselves from future economic instability, eventually focusing on high school education as a way to diversify industries and keep up with automation, said Brian Wiebe, who in 2012 founded local nonprofit Horizon Education Alliance, or HEA, to help lead that work.

That year, Wiebe and two dozen local and state political, business, nonprofit and education leaders visited Switzerland and Germany to learn more about the apprenticeship model. “We realized in the U.S., there was only a Plan A, a path to college,” he recalled. “We were not supporting the rest of our young people because there was no Plan B.”

HEA partnered with Elkhart County school districts and businesses, as well as with CareerWise, a youth apprenticeship nonprofit that works nationally. They began rolling out apprenticeships in 2019, eventually settling on a goal of increasing participation by 20 percent each year.

In 2021, Katie Jenner, the new secretary of education for Indiana, learned about Elkhart’s apprenticeships as she was trying to revamp high school education in the state so it better prepared students for the workforce. Elkhart, as well as six other apprenticeship pilot sites funded by Indianapolis-based philanthropy the Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation, provided a proof of concept for the apprenticeship model, said Jenner.

In December, the state adopted a new diploma system that includes an emphasis on experiential and work-based learning, through apprenticeships, internships and summer jobs.

Related: Schools push career ed classes ‘for all,’ even kids heading to college

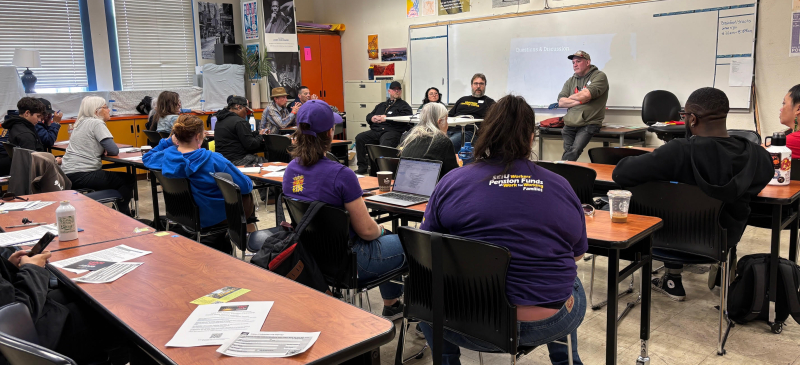

On a weekday this winter, 17 sophomores at Elkhart’s Concord High School were sitting at computers, creating resumes they planned to use to apply for apprenticeships. The students were among some 50 sophomores at the high school who’d expressed interest in apprenticing and met the school’s attendance and minimum 2.5 GPA requirements, out of a class of roughly 400. They would receive coaching and participate in mock interviews before meeting with employers.

Becca Roberts, a former English teacher who now oversees the high school’s college and career programs, said apprenticeships help convince students of the importance of habits like punctuality, clear communication and regular attendance. “It’s not from a book,” she said. “They’re dealing with real life.”

One student, Ava Cripe, said she hoped for an apprenticeship of some sort in the health care field. She’d only been a pet sitter and was nervous at the thought of having a professional job. “You’re actually going out and working for someone else, like not for your parents or your grandma, so it’s a little scary,” she said.

CareerWise Elkhart has recently beefed up its support for students and businesses participating in apprenticeships. It employs a business partnership manager and customer success managers who help smooth over issues that arise in the workplace — an apprentice who isn’t taking initiative, for example, or an apprenticeship that isn’t sufficiently challenging. “Before, if an issue came up, a business would just fire a student or a student would leave,” said Sarah Koontz, director of CareerWise Elkhart County. “We’re now more proactive.”

In Elkhart and across the state, the embrace of work-based learning has worried some parents who fear it will limit, not expand, their children’s opportunities. In previous generations, career and technical programs (then known as vocational education) were often used to route low-income and Black and Hispanic students away from college and into relatively low-paying career paths.

Anitra Zartman, Ty’s mother, said she and her husband were initially worried when their son said he wanted to go straight to work. They both graduated from college, and her husband holds a master’s degree. “We were like, ‘Don’t waste your talent. You’re smart, go to college.’” But she says they came around after seeing how the work experience influenced him. “His maturity has definitely changed. I think it’s because he has a responsibility that he takes very seriously,” she said. “He doesn’t want to let people down.”

Her eldest daughter, Senica Zartman, also apprenticed during her final two years of high school, as a teacher’s assistant. She is now in college studying education. “The apprenticeship solidified her choice,” Anitra Zartman said, and it helped her decide to work with elementary students. Anitra Zartman said she would encourage her two youngest children to participate in apprenticeships too.

Sarah Metzler, CEO of the nonprofit HEA, said apprenticeships differ from the vocational education of the past that tended only to prepare students for relatively low paid, entry-level jobs. With apprenticeships, she said, students must continually learn new skills and earn new licenses and industry certifications as part of the program.

Litzy Henriquez Monchez, 17, apprentices in human resources at a company of 50 people, earning $13.50 an hour. “I deal with payroll, I onboard new employees, I do a lot of translating. Anything that has to do with any of the employees, I deal with,” she said. She’s also earning an industry-recognized certification for her knowledge of a human resources management system, and says the company has offered to pay for her college tuition if she continues in the position.

Koontz said most companies pay for their apprentices to attend Ivy Tech, a statewide community college system, if they continue to work there. One is even paying for their apprentice’s four-year degree, she said.

Related: ‘Golden ticket to job security’: Trade union partnerships hold promise for high school students

Attracting employers has proven to be the biggest challenge to expanding youth apprenticeships — in Elkhart and beyond. In total, 20 companies worked with the Elkhart school districts last year, and 28 have signed on for this coming school year — only enough to employ about a third of interested students.

The obstacles, employers say, include the expense of apprentices’ salaries, training and other costs.

Metzler and others, though, point to studies showing benefits for employers, including cost savings over time and improved employee loyalty. And in Indiana, the Fairbanks foundation and other organizations are working on ways to reduce employer costs, including by developing a standard curriculum for apprenticeships in industries like health care and banking so individual companies don’t bear the costs alone.

Business leaders who do sign on say they are happy with the experience. Todd Cook, the CEO of Hoosier Crane Service Company, employs 10 high schoolers, including Ty Zartman, as engineering and industrial maintenance technician apprentices, approximately 10 percent of his staff. He said the pipeline created by the apprenticeship program has helped reduce recruiting costs.

“We’re starting to build our own farm system of talent,” he said. Students initially earn $13 an hour, and finish their apprenticeship earning $18. If they continue with the company, he said, they can earn up to $50 an hour after about five years. And if they go on to become trainers or mentors, Cook said, “Honestly, there is no ceiling.”

Related: A new kind of high school diploma trades chemistry for carpentry

Transportation has been a limiting factor too. There’s no public transit system, and students who can’t rely on their parents for rides are often out of luck. “We’d love to offer a bus to every kid, to every location, but we don’t have people to run those extra bus routes,” said Principal Pletcher.

The state has tried to help by investing $10 million to help students pay for costs such as transportation, equipment and certifications. Each school that provides work-based learning opportunities also receives an additional $500 per student.

Trump’s executive order called for the secretaries of education, labor and commerce to develop a plan by late August for adding 1 million new apprenticeships. The order does not set a date for reaching that milestone, and it applies to apprentices of all ages, not just high schoolers. Vinz Koller of Jobs for the Future said the goal is modest, and achievable; the number of youth apprenticeships has doubled just in the past few years, he said, and California alone has a goal of reaching 500,000 apprenticeships, across all ages, by 2029.

Still, the order did not include additional funding for apprenticeships, and the Trump administration’s proposed budget includes major cuts to workforce development training. In an email, a White House spokesperson said the administration had promoted apprenticeships through outreach programs but did not provide additional information including on whether that outreach had a focus on youth apprenticeships.

Back in Elkhart, Ty Zartman, the Hoosier Crane apprentice, has begun his technician job with the company after graduating in early June. He is earning $19 an hour. He is also taking a class at the local community college on electrical work and recently received a certificate of completion from the Department of Labor for completing 2,000 hours of his apprenticeship.

Anitra Zartman said she wishes he’d attended more school events like pep rallies, and sometimes worried he wasn’t “being a kid.” But Ty said his supervisor is “super flexible” and he was able to go to the winter formal and prom. “I think I still live a kid life,” he said. “I do a lot of fun things.”

Of his job, he said, “I love it so much.”

Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at [email protected].

This story about high school apprenticeships was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.