A Black History Month event, canceled. A lab working to fight hunger, shuttered. Student visas revoked, then reinstated, uncertain for how long. Opportunities for students pursuing science careers, fading.

The first six months of the Trump administration have brought a hailstorm of changes to the nation’s colleges and universities. While the president’s faceoffs with Harvard and Columbia have generated the most attention, students on campuses throughout the country are noticing the effects of the administration’s cuts to scientific and medical research, clampdown on any efforts promoting diversity equity and inclusion (DEI), newly aggressive policies for students with loan debt, revoking of visas for international students and more.

Many of the administration’s actions are being challenged in court, but they are influencing the way students interact with each other, what support they can get from their institutions — and even whether they feel safe in this nation.

The Hechinger Report traveled to campuses around the country to look at what these changes mean for students. Reporters visited universities in four states — California, Illinois, Louisiana and Texas — to understand this new era for higher education.

Related: Interested in more news about colleges and universities? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

Louisiana State University

BATON ROUGE, La. — Last fall, Louisiana State University student A’shawna Smith had an idea for a new campus group to educate students about their legal rights and broader problems in the criminal justice system. Smith, a sociology major, had spent the prior summer interning at a law firm and noticed how many clients didn’t know their rights after an arrest.

Smith, now a rising senior, called it The Injustice Reform and soon recruited classmates and a campus adviser. They wrote a mission statement and trained as student group leaders. On Feb. 20, LSU’s student government, which awards money to campus groups that comes from student fees, gave them $1,200; Smith and her classmates planned to use the award to recruit members and organize events.

But on April 8, Injustice Reform’s treasurer received a text message from Cortney Greavis, LSU’s student government adviser. She said LSU was rescinding the money: The group’s mission statement ran afoul of new federal and state restrictions on DEI. Its mission mentions racial disparities and police brutality, but the organizers were never told which words violated the rules. Smith and fellow leaders started chipping in their own money to keep the group going: $10 here and there, whatever they could afford, said Bella Porché, a rising senior on the group’s executive board.

Canceling awards to student groups is one way students say administrators at LSU, the state’s flagship university, have restricted what they can do and say since the U.S. Department of Education wrote to schools and colleges nationwide on Valentine’s Day. The letter described DEI efforts — designed to rectify current and historic discrimination — as discriminatory and threatened schools with the loss of federal money unless they ended the consideration of race in admissions, financial aid, housing, training and other practices.

Since the letter, discussion of DEI on campus “has become an anti-gay, anti-Black sort of conversation,” said Emma Miller, a rising senior and elected student senator. “People who are minorities don’t feel safe anymore, don’t feel represented, don’t feel seen, because DEI is being wiped away and their university is not saying anything.”

In a March 7 report, the university detailed dozens of changes made to comply with the letter’s demands. For example, it ended any preference granted to students from historically underrepresented groups for certain privately funded scholarships; opened membership in school-funded student organizations — like a women-in-business group — to all; and canceled activities perceived to emphasize race, even a fitness class kicking off Black History Month.

Student government leaders say the restrictions hinder their ability to operate. Rising junior Tyhlar Holliway, a member of the student government’s Black Caucus, said school administrators essentially shut down the caucus’ proposal that the student government issue a statement after the Department of Education letter in support of DEI programs and initiatives.

LSU public relations staff did not respond to interview requests or to an emailed list of questions, and the school’s civil rights and Title IX division director declined to speak.

Miller said administrators have told student leaders that all their proposed legislation must be reviewed by the school’s general counsel for compliance with the March 7 guidelines. The administration, for example, blocked a student government bill to fund a Black hair care event designed to help students prepare for career and professional opportunities, said senior Paris Holman, a student government member. “We have conferences and interviews and need to know how to take care of our hair,” said Holman, who is Black.

Students have also tailored the language of other bills to avoid the appearance of support for DEI. Holman said that in one case the student senate changed the language in a bill funding an end-of-year event for a minority student organization to remove any reference to the organization as serving minority students.

The school also overrode student government decisions about which groups, like A’shawna Smith’s, could be funded by student fees. In February, the student government voted to provide $641 to help a pre-med student, who is Black, attend a student medical education conference, in part so she could share what she’d learn with other pre-med students. A few weeks later, she received an email from Greavis, the student government adviser, saying she wouldn’t be able to attend with university funds because that money could no longer be used for “DEI-related events, initiatives, programs, or travel.” Greavis didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

The email didn’t specify why the medical conference crossed the line. But the sponsoring organization’s mission statement notes its commitment to “supporting current and future underrepresented minority medical students,” and a conference plenary speaker was scheduled to address the “enduring case for DEI in medicine.” Fewer than 6 percent of doctors are Black and research has shown improved health outcomes for Black patients who are seen by physicians of the same race.

“It doesn’t feel like a democracy,” said Holman of serving in student government at this moment.

She and other students say the university’s actions are starting to change the broader culture at LSU, which serves nearly 40,000 undergraduate and graduate students on its campus of Italian Renaissance buildings shaded by magnolias and Southern live oaks. About 60 percent of students are white and 18 percent are Black, according to federal data.

Mila Fair, a rising sophomore journalism major and a reporter for the campus TV station, said students tell her they’re afraid to join protests, in part because of LSU’s new anti-DEI rules and the national crackdown on student demonstrations. Those who do attend are often afraid to go on camera with her, she said.

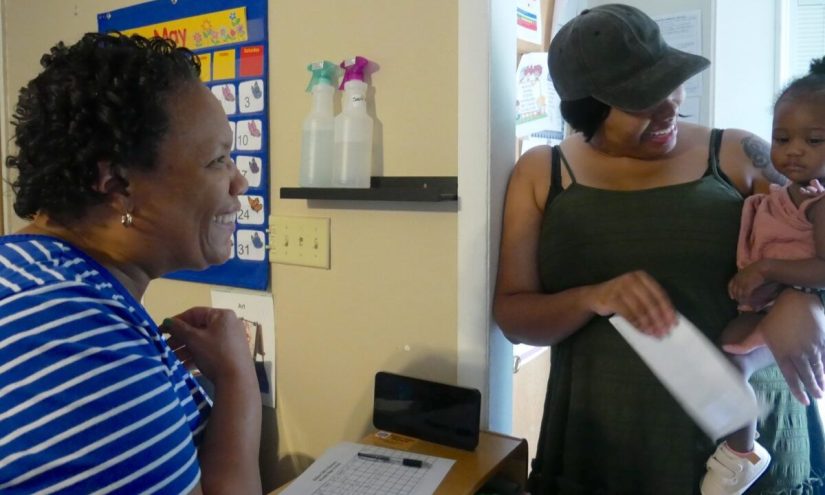

Latin American studies professor Andrew Sluyter said administrators normally listen to the student government — even more than to the faculty government — but now worry about students getting the school into “political hot water.” He had his own run-in with the DEI ban: As part of a February effort to scrub school websites of diversity references, in which the university purged hundreds of webpages referencing DEI-related content, LSU deleted a 2022 press release announcing a prestigious fellowship he’d won that mentioned “higher education’s racial inequities.”

Students recognize the pressure LSU is under from the federal government, but they want administrators to stand up for them, said graduate student Alicia Cerquone, a student senator. “We want some sort of communication from the university that shows commitment to its community, that they have our backs and they’ll protect students,” she said.

— Steven Yoder

The University of California, Berkeley

BERKELEY, Calif. — Since early April, Rayne Xue, a junior at the University of California, Berkeley, has watched with trepidation as the Trump administration has taken one step after another to limit international students’ access to American higher education.

First came the abrupt cancellation, then reinstatement, of visas for 23 Berkeley students and recent graduates. Then the government cut off Harvard’s ability to enroll international students — a move since blocked by a federal judge — raising fears that something similar could happen at Berkeley. And late last month, as this year’s graduates were celebrating their recent commencements, Secretary of State Marco Rubio paused interviews for all new student visas and announced he would “aggressively revoke” those of Chinese students.

Xue, who is from Beijing and won a student senate seat this past spring on a platform of supporting international students, said the administration’s actions strike at a critical part of campus life at Berkeley.

“College is the opportunity of a lifetime to unlearn prejudices and embrace new perspectives, neither of which is possible without a student body that comes from a wide range of geographic and cultural backgrounds,” she said.

About 16 percent of UC Berkeley’s more than 45,000 students come from outside the United States to study at the crown jewel of California’s public research university system, where creeks run through campus beneath cooling redwoods and parking spaces are set aside for Nobel laureates. China, India, South Korea and Canada send the biggest numbers. International students pay higher tuition than California residents, boosting the university’s coffers and subsidizing some of their peers. Many of them conduct cutting-edge research in fields like computer science, engineering and chemistry.

Now the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown, magnified by the yanking of billions in federal research dollars, has international students worried about their future on campus. Many are changing their behavior to avoid scrutiny: Some canceled travel plans and many said they avoid walking near any campus protests in fear of being photographed.

“It’s difficult for international students to feel secure when they cannot anticipate what the administration might charge against them next — or whether they might be unfairly targeted,” said one global studies major who asked not to be identified for fear of attracting retaliation.

Tomba Morreau, a rising junior from the Netherlands studying sociology, said he stopped posting about politics on social media — just in case.

That kind of self-censorship troubles Paul Fine, co-chair of the Berkeley Faculty Association, which represents about a fifth of the university’s tenure-track faculty.

Federal policies are “creating this culture of fear where people start to censor themselves and try to stay under the radar and not show up in their full selves, whether for academic work or activism,” he said.

Related: International students are rethinking coming to the U.S. That’s a problem for colleges

International students in Fine’s classes told him they wanted to attend a recent protest against federal threats to higher education but were afraid of the consequences, he said. Others told him they were skipping academic conferences outside the United States that they otherwise would have attended.

“Berkeley really prides ourselves on being an intellectual hub that convenes people from all over the world to work on the most important problems,” Fine said. Now that identity is at risk, he said, especially as actual and threatened cuts to grants make it harder for faculty to hire international graduate students and postdocs.

Most poignant, he said, was hearing from demoralized Chinese students who left a repressive government to come to the United States only to see attacks on academic freedom replicated here.

We want to hear from you.

Are you a student, professor, staff or faculty member? Our journalists want to know how the Trump administration is affecting higher education and life on your college campus.

Xue said she hopes the crisis facing universities would draw attention to the challenges international students face, including limited financial aid and the stereotype that all of them are wealthy. With her colleagues in student government, she is lobbying for Berkeley to spend more on the international office, which provides one-on-one advising on visa issues and employment.

For Lily Liu, a Chinese computer scientist, 2025 was shaping up to be a year of milestones. She graduated with a doctorate last month, has a job lined up at a leading artificial intelligence company and is engaged to be married in November.

But the Trump administration’s changing policies toward international scholars have complicated celebrations for Liu, who’s in a federal program that extends her visa for up to a year beyond graduation so she can gain work experience here. She canceled summer travel plans with her family, concerned she might not be let back into the country. And she’s considering moving her wedding to the United States from China, even though many of her relatives wouldn’t be able to attend.

“For international students, every policy affects us a lot,” she said. So Liu is careful. After the publication of her thesis was delayed, she visited Berkeley’s international office to make sure the setback wouldn’t affect her work permit. Her fiancé has a green card, which should theoretically mean his immigration status is more stable. But these days, she said, who knows?

— Felicia Mello

The University of Texas at San Antonio

SAN ANTONIO, Texas — Growing up here, Reina Saldivar had always loved science — all she wanted to watch on TV was “Animal Planet.” Yet until she applied on a whim to a program for aspiring researchers after her first year at the University of Texas at San Antonio, she assumed she would spend her life as a lab technician, running cultures.

The program, Maximizing Access to Research Careers, or MARC, was started by the National Institutes of Health decades ago at colleges around the country to prepare students, especially those from historically underrepresented backgrounds, for livelihoods in the biomedical sciences.

Saldivar got in. And through the program, she spent much of her time on campus in a university lab, helping develop a carrier molecule for a new Lyme disease vaccine. Now Saldivar, who graduated this spring, plans to eventually return to academia for a doctorate.

“What MARC taught me was that my dreams aren’t out of reach,” she said.

Saldivar is among hundreds who’ve participated in the MARC program since its 1980 founding at the University of Texas at San Antonio. She may also be among the last. In April, the university’s MARC program director, Edwin Barea-Rodriguez, opened his email inbox to find a form letter terminating the initiative and advising against recruiting more cohorts.

The letter cited “changes in NIH/HHS [Health and Human Services] priorities.” In recent months, the Trump administration has canceled at least half a dozen programs meant to train scholars and diversify the sciences as part of an effort to root out what the president labels illegal DEI.

In a statement to The Hechinger Report, NIH said that it “is committed to restoring the agency to its tradition of upholding gold-standard, evidence-based science” and is reviewing grants to make sure the agency is “addressing the United States chronic disease epidemic.”

With MARC ending, Barea-Rodriguez is searching for a way to continue supporting current participants until they graduate next academic year. Without access to federal money, however, the young scientists are anxious about their futures — and that of public health in general.

“It took years to be where we are now,” said Barea-Rodriguez, who said he was not speaking on behalf of his university, “and in a hundred days everything was destroyed.”

UTSA’s sprawling campus sits on the northwest edge of San Antonio, far from tourist sites like the Alamo and the River Walk. Forty-four percent of the nearly 31,000 undergraduate students are the first in their families to attend college; more than 61 percent identify as Hispanic or Latino. The university was one of the first nationwide to earn Department of Education recognition as a Hispanic-serving institution, a designation for colleges where at least a quarter of full-time undergraduates are Hispanic.

When Barea-Rodriguez arrived to teach at the school in 1995, many locals considered it a glorified community college, he said. But in the three decades since, the investments NIH made through MARC and other federal programs have helped it become a top-tier research university. That provided students like Saldivar with access to world-class opportunities close to home and fostered talent that propelled the economy in San Antonio and beyond.

The Trump administration has quickly upended much of that infrastructure, not only by terminating career pipeline programs for scholars, but also by pulling more than $8.2 million in National Science Foundation money from UTSA.

One of those canceled grants paid for student researchers and the development of new technologies to improve equity in math education and better serve elementary school kids from underrepresented backgrounds in a city that is about 64 percent Hispanic. Another aimed to provide science, technology, engineering and math programming to bilingual and low-income communities.

UTSA administrators did not respond to requests for comment about how federal funding freezes and cuts are affecting the university. Nationwide, more than 1,600 NSF grants have been axed since January.

Related: So much for saving the planet. Climate careers, plus many others, evaporate for class of 2025

In San Antonio, undergraduates said MARC and other now-dead programs helped prepare them for academic and professional careers that might have otherwise been elusive. Speaking in a lab remodeled and furnished with NIH money, where leftover notes and diagrams on glass erase boards showed the research questions students had been noodling, they described how the programs taught them about drafting an abstract, honing public speaking and writing skills, networking, putting together a résumé and applying for summer research positions, travel scholarships and graduate opportunities.

“All of the achievements that I’ve collected have pretty much been, like, a direct result of the program,” said Seth Fremin, a senior biochemistry major who transferred to UTSA from community college and has co-authored five articles in major journals, with more in the pipeline. After graduation, he will start a fully funded doctoral program at the University of Pittsburgh to continue his research on better understanding chemical reactions.

Similarly, Elizabeth Negron, a rising senior, is spending this summer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, researching skin microbiomes to see if certain bacteria predispose some people to cancers.

“It’s weird when you meet students who didn’t get into these programs,” Negron said, referring to MARC. “They haven’t gone to conferences. They haven’t done research. They haven’t been able to mentor students. … It’s very strange to acknowledge what life would have been without it. I don’t know if I could say I’d be as successful as I am now.”

With money for MARC erased, Negron said she will probably need a job once she returns to campus in the fall so she can afford day-to-day expenses. Before, research was her job.

“Without MARC,” she said, “it becomes a question of can I at least cover my tuition and my very basic needs.”

— Alexandra Villarreal

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

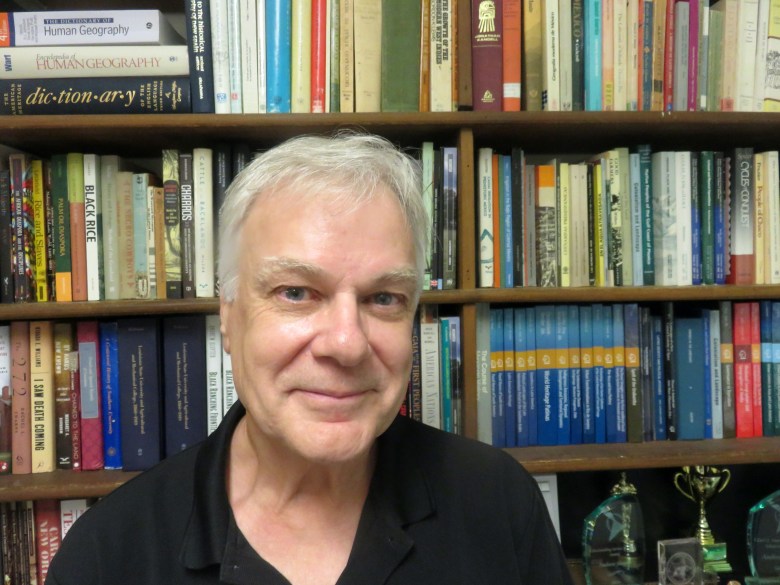

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — When Peter Goldsmith received notice in late January that his Soybean Innovation Lab at the University of Illinois would soon lose all of its funding, he had no idea it was coming. Suddenly Goldsmith, the lab’s director, had to tell his 30 employees they would soon be out of a job and tell research partners across Africa that operations would come to a halt. The lab didn’t even have money to water its soybean fields in Africa.

One employee, Julia Paniago, was in Malawi when she got the news. “We came back the next day,” she said of her team, “and it was a lot of uncertainty. And a lot of people cried.”

The University of Illinois’ Soybean Innovation Lab (SIL) was part of a network of 17 labs at universities across the country, all working on research related to food production and reducing global hunger, and all funded through the U.S. Agency for International Development — until the Trump administration shut down USAID.

Soybeans — which provide both oil and high-protein food — aren’t yet commonly grown in Malawi. SIL researchers have been working toward two related goals: helping local farmers increase soybean production and ameliorate malnutrition and generating enough interest in the crop there that a new export market will open for American farmers.

The lab’s researchers work in soybean breeding, economics and mechanical research as well as education. They hope to show that soybean production in Africa is worth further investment so that eventually the private sector will come in after them.

“The people who work at SIL, they like being right at the frontier of change,” Goldsmith said. “It’s high-risk work — that’s what the universities do, that’s what scientific research is about.”

UI, the state’s flagship with a sprawling campus spread between the cities of Urbana and Champaign, is noted for its research work, especially agricultural research.

Labs and researchers across the university lost funding in cuts made by the Trump administration; more than $25 million from agencies including NIH, NSF and the National Endowment for the Humanities was cut, Melissa Edwards, associate vice chancellor for research and innovation, said, a total of 59 grants amounting to 3.6 percent of their overall federal grant portfolio.

Annette Donnelly, who just received her doctorate in education, is among those affected. Her research focuses on educating malnourished children in Africa and developing courses to help Africans learn how to process soybeans into oil.

Related: The college degree gap between Black and white Americans was always bad. It’s getting worse

In April, SIL was handed a lifeline — an anonymous $1 million gift that will keep the lab running through April 2026. The donation wasn’t enough for Goldsmith to rehire all of his employees; SIL’s annual operating budget before the USAID cuts was $3.3 million (and would have kept things running through 2027). But, he said, the money will allow SIL to continue its research in the Lower Shire Valley in Malawi, a project he hopes will attract future donors to fund the lab’s work.

The April donation saved Donnelly’s job, but her priorities shifted. “We’re doing research,” she said, “but we’re also doing a lot of proposal writing. It has taken on a much greater priority.”

Donnelly hopes to attract more funding so she can resume research she had started in western Kenya, demonstrating that introducing soy into children’s diets increased their protein intake by up to 65 percent, she said.

The impact that funding cuts will have on researchers at the soybean lab pales in comparison to the impact on their partners in Africa, Donnelly emphasized. There, she said, the cuts mean processors will likely slow production, limiting their ability to deliver soy products. “The consequences there are much bigger,” she said.

The Soybean Innovation Lab was funded through the Feed the Future initiative, a program to help partner countries develop better agricultural practices that began under the Obama administration in 2010. All 17 Feed the Future innovation labs funded through USAID lost funding, except for the one at Kansas State University, which studies heat-tolerant wheat.

The soybean lab’s office is housed on a quiet edge of the Illinois campus in a building once occupied by the university’s veterinary medicine program. Across the street, rows of greenhouses are home to the Crop Science Department’s experiments.

There, Brian Diers is breeding soybean varieties that resist soybean rust, a disease that’s been an obstacle to ramping up soybean production across sub-Saharan Africa. A professor emeritus who is retired, Diers works part-time at SIL to assist with soybean breeding. The April donation wasn’t enough to cover his work. Now he volunteers his time.

“ If we can help African agriculture take off and become more productive, that’s eventually going to help their economies and then provide more opportunities for American farmers to export to Africa,” he said.

Goldsmith drew an analogy between his lab’s work and the state of American agriculture in the 1930s. As the Dust Bowl swept through the Great Plains, Monsanto or another company could have stepped in to help combat it, but didn’t. Public land-grant universities did.

“That’s where the innovation comes from, from the public land grants in the U.S.,” Goldsmith said. “And now the public land grants still work in U.S. agriculture but also in the developing world.”

Commercial soybean producers hesitate to dip their toes into unproven markets, he said, so it’s SIL’s job to demonstrate that a viable market exists. “That was our secret sauce, in that lots of commercial players liked the products, the technologies we had, and wanted to move into the soybean space, but it wasn’t a profitable market,” Goldsmith said of the African soybean market.

Diers said federal funding cuts imperil not just the development of commerce and global food production but the next generation of scientists as well.

“We could potentially lose a generation of scientists who won’t go into science because there’s no funding right now,” he said.

— Miles MacClure

Contact editor Lawrie Mifflin at [email protected] or 212-678-4078. Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at [email protected].

This story about international students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.