Belonging and mattering are crucial for creating educational environments where learners feel connected to their department and classmates (Hale et al., 2019). Student success has become a major outcome measure for many academic units (Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education, 2005 and Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education, 2025). Researchers have found that learners’ sense of belonging enhances psychological flexibility, learner satisfaction, motivation, and professional identity, thereby increasing student success (Carter et al., 2023 and Tejero-Vidal et al., 2025). Measuring a learner’s perception of belonging can be challenging for educators. To support this effort, a social-ecological model has been developed to conceptualize the different layers that contribute to a learner’s sense of belonging (Johnson, 2022). The Departmental Sense of Belonging (DeSBI) tool specifically measures this sense within the context of department and peer relationships (Knekta et al., 2020).

I explored how an increased involvement in the belonging social-ecological model was associated with learners’ sense of belonging within their department. The goal was to help departments refine their model to enhance learners’ connection to faculty and peers, thereby increasing learners’ success. The hypothesis was that higher interactions in the social-ecological model would correlate with a higher sense of belonging. Sixty-eight learners from three allied health programs completed the survey, which found the results a statistically significant association between the learner’s involvement in the belonging social ecological model and a learner’s sense of belonging to a department.

Practical Application of the Belonging Social-Ecological Model

The study underscores the pivotal role of departmental culture and environment in shaping a learner’s sense of belonging. This is an essential consideration for departments when evaluating the factors provided to learners at each level of the belonging social ecological model.

Intrapersonal Level

Activities within the interpersonal level are journaling, professional development, and mental health practices. It is crucial for faculty to consider encouraging learners to journal at the end of a class session or to include journaling as a graded activity within their course. Supporting learners in building these habits helps foster psychological flexibility and self-awareness. This approach can also provide an opportunity strengthen the therapeutic alliance between individual faculty.

Interpersonal Level

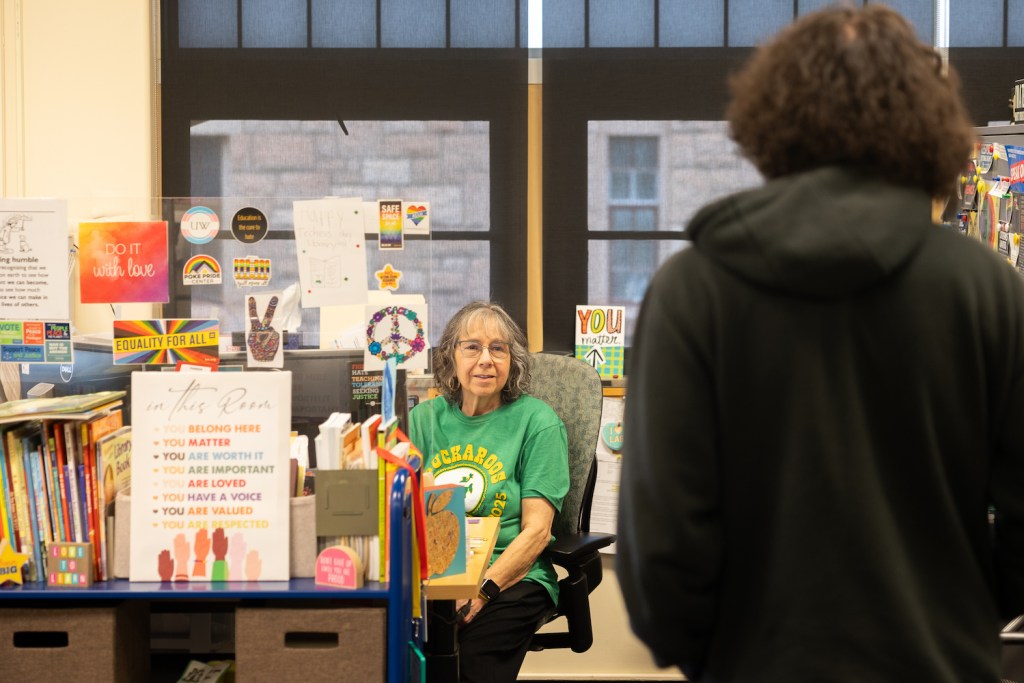

Activities within this level include meals with classmates and faculty, physical activities, and social gatherings. Faculty should strongly consider whether their academic space provides the area for learners to study and have meals together. If your department lacks such space, advocating for one in or near your department should be a priority. If your academic unit has the gathering space, it will be important for faculty to evaluate if it will attract learners to use it effectively, or if learners will avoid the areas because of its set-up and location. Ensuring a dedicated space is not only available but actively used is a critical step for faculty when evaluating their effectiveness in fostering a sense of belonging within the department.

Additionally, faculty should encourage learners to spearhead the organization of social events outside the department so to strengthen connections between one another. With mentorship and engagement from faculty, learners will be empowered to create inclusive events that help all feel welcome.

Institutional Level

The institutional level considers what activities are offered by the university to the learners. Every university, regardless of its size, hosts various events each week for its learners. It is crucial for faculty to consider how their learners are engaging with university announcements about these events. Faculty should consider how the department reinforces these activities on its own announcement board. Should faculty hang signs near the department, or employ other creative strategies to ensure learners are fully informed about campus activities?

Community and Societal Level

The social ecological model is the community and society encompasses activities that extend beyond campus and occur within the community and at the society level. Each university is an integral part of the community in which it is located. Therefore, it is important for faculty to consider how learners are kept informed about the events occurring within the community they live. Ensuring the department highlights events, beyond the favorite coffee shop, restaurant, or activity spot, is crucial for fostering a sense of belonging. Considering each community offers unique experiences, making sure learners are aware of these activities is important. By combining the dissemination of institution activities with community events, faculty can address two domains with one strategic plan.

Physical and Virtual Space

Physical and virtual spaces are in the outer most layer in this social-ecological model and include the structure of class breaks, classroom setup, and online activities. Faculty should consider how physical and virtual learning environments impact social connections. For example, it is important for faculty to thoughtfully consider how breaks are structured – not just when they are given. Encouraging learners to leave the room for a short walk outside with peers, play a quick game of four-square, or throw a frisbee is beneficial, as it promotes learners to be active shift their mindset, and foster conversations beyond classroom content.

A final consideration involves the layout of the classroom. Is the classroom arranged traditionally with everyone facing forward, or can it be reorganized into pods or small groups, which will facilitate discussion during group projects? If the goal is to engage the entire room, can the seating be arranged into a large circle to allow learners to see each other’s body language while speaking? These small yet significant environmental factors can impact the learning environment and the sense of belonging for each learner in the room.

Conclusion

Increased engagement across all layers of the belonging social-ecological model significantly enhances the learners’ sense of connection and inclusion. This sense of belonging is not a peripheral benefit – it is foundational to learner motivation, participation, and overall success. Faculty play a key role in implementing thoughtful strategies that promote belonging at every level of the belonging social ecological model. In doing so, they help create a dynamic and inclusive learning community where every learner can thrive – leading to greater success and personal fulfillment in their learners’ academic journey.

Dustin Cox, PT, DPT, PhD, is an Associate Professor at Augusta University and a licensed physical therapist with advanced certifications in therapeutic treatment for Parkinson’s and lymphedema. He received his Doctor of Physical Therapy in 2011 and his Ph.D. in Health Sciences in 2023 from Northern Illinois University. Since 2016, Dustin has been dedicated to helping learners achieve their goals in becoming effective healthcare practitioners. Currently, Dustin teaches in a DPT program and clinically works with clients that are in the pediatric stage of life and clients with bleeding disorders.

References

Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education. (2025, March 15). 2018 and 2023 ACOTE Standards. Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Eudcation. https://acoteonline.org/accreditation-explained/standards/

Carter, B. M., Sumpter, D. F., and Thruston, W. (2023). Overcoming Marginalization by Creating a Sense of Belonging. Creative nursing, 29(4), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/10784535231216464

Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education. (2025, March 15). Accreditation Handbook. Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy. https://www.capteonline.org/faculty-and-program-resources/resource_documents/accreditation-handbook

Hale, A. J., Ricotta, D. N., Freed, J., Smith, C. C., and Huang, G. C. (2019). Adapting Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Resident Wellness. Teaching and learning in medicine, 31(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1456928

Johnson, Royel. (2022). A socio-ecological perspective on sense of belonging among racially/ethnically minoritized college students: Implications for equity-minded practice and policy. New Directions for Higher Education, Spring 2022, pages 59 – 68. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20427

Knekta, E., Chatzikyriakidou, K., and McCartney, M. (2020). Evaluation of a Questionnaire Measuring University Students’ Sense of Belonging to and Involvement in a Biology Department. CBE life sciences education, 19(3), ar27. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-09-0166

Tejero-Vidal, L. L., Pedregosa-Fauste, S., Majó-Rossell, A., García-Díaz, F., and Martínez-Rodríguez, L. (2025). Building nursing students’ professional identity through the ‘Design process’ methodology: A qualitative study. Nurse education in practice, 83, 104256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2025.104256