The way higher institutions define and acknowledge student success in higher education today is changing rapidly. Today, diplomas and transcripts are no longer the benchmarks for measuring the success rate of students in their academics. To define success, you have to consider a complete and holistic journey and vision. Factors like the student’s academic excellence, mental and physical growth, and preparation for what comes next are increasingly becoming key to defining academic success. This is why universities are looking beyond enrolment figures, they are now more focused on helping their students thrive academically, socially, and professionally.

This brings us to the role of modern digital marketing tactics and advanced CRM tools. Colleges can create an environment that supports every student with the right resources they need to succeed, using the data-driven outreach and personalized support that these tools offer. In this blog post, we’ll explore the true meaning of student success and what key metrics are best placed to measure student success in higher education. We’ll also show you how marketing automation and CRM platforms (including HEM’s own Mautic for Education and Student Portal) can help drive real student achievement. Read on to find out what strategies and tools are best suited to define modern student success.

Redefining Student Success Metrics in Higher Education: Beyond GPAs and Graduation Rates

Who you ask about the definition of academic success will also determine the type of answer you get. Administrators might lean towards metrics and retention rates. Students tend to have a more personal definition of success, like having supportive mentors, developing confidence, and building lasting connections.

This brings us to the question: What is the definition of student success? The definition of student success encompasses building communication skills and critical thinking activities, career or grad school readiness. In essence, a successful student grows through campus life, engages with the community, and adequately prepares themself for future opportunities.

Below are components of a comprehensive student success definition:

- Academic Achievement: Mastering course material and maintaining strong GPAs

- Persistence and Retention: Continuing enrolment term after term until graduation

- Personal Development: Cultivating critical thinking, communication skills, and emotional intelligence

- Engagement and Belonging: Finding community through meaningful campus involvement

- Career Readiness: Building the confidence and skills needed for post-graduation success

As EDUCAUSE, a prominent education technology organization, points out, student success programs “promote student engagement, learning, and progress toward the student’s own goals through cross-functional leadership and the strategic application of technology.” This reaffirms the fact that true success calls for a harmonious relationship between human connection and technology.

Measuring What Matters: The Metrics of Achievement

How do we truly and correctly measure student success if we say that there are many sides to it? What is the definition of a successful student, and how to measure student success in higher education? While this question has intrigued higher educational professionals for decades, today’s schools are finding the right answers by combining traditional metrics and emerging indicators.

Traditional measurements include retention rates (are students returning each semester?), graduation rates (are they completing their degrees?), and academic performance (are they mastering the material?).

Now, these numbers matter. They help us tell to a reasonable degree if students are progressing toward their educational goals, or not. However, there’s a richer story to be told beyond these statistics, and you’ll learn about it shortly.

Student success metrics commonly include:

- Retention Rates: The percentage of students who return for subsequent terms

- Graduation Rates: How many students complete their degrees within expected timeframes

- Academic Performance: Beyond grades—how students grow intellectually over time

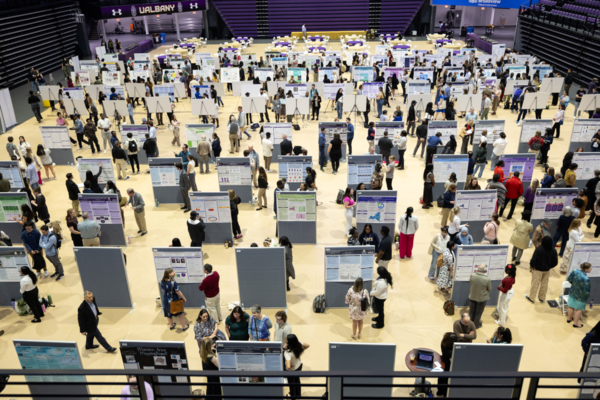

- Student Engagement: Participation in everything from research opportunities to campus events

- Student Satisfaction: Feedback that reveals how students experience their education

- Post-Graduation Outcomes: Career placement, graduate school acceptance, and alumni achievements

Away from these quantifiable measures, today’s schools value the essence of student-defined success. For them, it could be a first-generation student finding their voice, an international student building cross-cultural friendships, or a working parent balancing studies with family life. The schools that manage to combine statistical trends with individual stories will ultimately get the most complete picture of things.

Examples: ULM developed FlightPath, an open-source advising system for degree audits, early alerts, and “What If?” planning. It is designed to help you determine your progress toward a degree.

Source: ULM FlightPath

Digital Marketing: Setting the Stage for Success

What do marketing strategies have to do with student success? What does digital marketing contribute to student success? Higher education marketing and student success are interconnected through a series of key touchpoints.

The path to college student success often begins with that first Instagram post that catches a high school junior’s eye or that personalized email that addresses their specific interests. It is all part of the coordinated digital marketing campaigns that today’s schools employ, to great success.

Here’s how digital marketing strategies can help nurture student success:

- Attracting the right-fit students: When marketing materials paint an authentic picture of campus culture, incoming students arrive with realistic expectations and are more ready to engage.

- Personalized communication: Tailored messages that speak to individual aspirations create early connections. When a prospective engineering student receives content about robotics competitions or research labs, they begin envisioning their place in your community.

- Seamless onboarding: The summer before freshman year can be overwhelming. Automated campaigns that introduce new students to campus resources, share advice from current students, and foster peer connections help transform nervousness into excitement.

- Feedback loops: Savvy marketing teams don’t just broadcast – they listen. Social media monitoring and regular surveys help identify pain points before they become barriers to success.

Examples: Gonzaga’s English Language Center moved from siloed data to a Student Success CRM on Salesforce, improving collaboration and early-alert capabilities for ESL learners.

Source: Gonzaga University

CRM Tools: The Backbone of Student Support

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems are now important tools for tracking and supporting the student journey, especially in today’s data-driven world. These platforms present themselves as centralized hubs that help schools track student progress, identify potential challenges, and carry out timely interventions.

Colleges can transform how they engage with students at every stage using the right CRM. Take this scenario for example: A first-year student misses out on many classes and fails to log into the learning management system for two weeks. While this might have gone on without being detected in the past, probably until midterm grades showed a significant gap, not anymore. With a CRM, a trigger will set off based on this pattern and send automatic alerts to the students’ advisor, who can now contact support resources to arrest the decline before it further spirals.

Example: King’s College uses CRM Advise to flag risk factors, like missed classes, and automatically route alerts to advisors and support centers.

Source: King’s College – CRM Advise

Here are six ways CRM tools elevate student success in higher education:

- Centralizing the 360° Student View: Modern CRMs integrate data from admissions, advising, financial aid, and student life to create comprehensive student profiles. When an advisor can see that a struggling student is also working 30 hours weekly, they can provide more targeted support.

- Enabling Early Alerts: By analyzing patterns like missed assignments or decreased LMS activity, CRMs can identify at-risk students before a crisis develops.

- Automating Support Workflows: Smart CRMs ensure consistent communication throughout the student journey. From congratulatory messages when students ace exams to gentle nudges when they miss classes, automated workflows maintain continuous engagement without overwhelming staff.

- Providing Data-driven Insights: Institutions can analyze which interventions are best-suited to promote student success, using comprehensive data collection.

- Streamlining Administrative Processes: By simplifying registration, financial aid processes, and advising appointments, CRMs eliminate frustrating barriers that might otherwise derail student progress.

- Promoting Community: Many platforms include features that connect students with mentors, study groups, and support communities. These all help to nurture the sense of belonging that anchors students during challenging times.

With solutions like Mautic by HEM, schools can enjoy robust CRM and marketing automation tailored specifically for them. The platform provides a central hub where you can manage all of your leads, applicants, agents, and parent contacts, enabling personalized support throughout the student lifecycle.

Example: Michael Vincent Academy, a Los Angeles-based beauty school, sought to enhance its student recruitment efficiency by streamlining lead management and follow-up processes. With HEM’s Mautic CRM, the academy automated key marketing tasks and introduced lead scoring, enabling staff to focus on high-value prospects. This allowed the team to dedicate more time to building meaningful connections with prospective students, ultimately improving recruitment outcomes.

Source: HEM

HEM’s Student Portal combines online application creation and management, SIS functionality, and lead-nurturing tools in one centralized system. As a student, this is designed to help you manage your journey – from initial application to enrolment to graduation and beyond.

As a school, using these specialized tools can help you address your institution’s unique needs and leverage the capacity of generic CRMs.

Source: HEM

Example: Students at Western Michigan University (WMU) use the Student Success Hub’s CRM to schedule and manage appointments, review advising notes, work on success plans, and tasks.

Source: WMU Student Success Hub Training

The Impact of Dedicated Success Programs

One of the key ingredients of college student success is the use of structured programming that helps students navigate important stages of their academic journey. Many schools have found value in offering a student success class or course, such as a freshman seminar or “College 101” course that equips students with essential skills and connections.

What is a student success class in college? It’s a course designed to help students be successful in college. It aims to help students properly navigate both academic requirements and college culture. Here is a list of subjects that these classes typically cover:

- Effective study strategies tailored to college-level expectations

- Time management techniques for balancing academic and personal demands

- Campus resource navigation, introducing students to everything from tutoring to counselling

- Financial literacy skills to manage college costs

- Stress management and wellness practices

- Career exploration and professional development

Research continues to show that the students who complete these courses earn more credits and have a higher graduation rate than those who don’t participate.

The Power of Storytelling in Student Success Marketing

By channelling authentic storytelling into their marketing narratives, schools can connect with prospective and current students. Stories have a way of transforming abstract content as “retention initiatives” into relatable human experiences that inspire action.

What if you created a series featuring diverse student voices? Think of the impact it can have. Think of first-generation students who initially had doubts about themselves but connected with mentors who had faith in them, the transfer student who found unexpected opportunities, or the international student who calls the school home.

Not only do these narratives attract prospective students, but they remind the current ones that challenges are not special and that success is very much achievable.

Tips to Boost Student Success with Marketing and CRM

Institutions looking to take advantage of digital marketing and CRM tools more effectively should consider these practical strategies.

- Use Data to Personalize Outreach: Segment your communications based on student interests, challenges, and milestones to provide relevant support throughout their journey.

- Implement Early Alert Systems: Configure your CRM to identify warning signs like decreased engagement or academic struggles, enabling timely, personalized interventions.

- Integrate Your Systems: Ensure your marketing automation, CRM, and student information systems communicate seamlessly for a complete view of each student’s experience.

- Maintain Consistent Communication: Develop messaging flows that accompany students from prospective inquiry through graduation while remaining authentic and supportive.

- Leverage Student Feedback for Content: Gather testimonials and success stories that inspire current students and set realistic expectations for prospects.

- Train Your Team on Tools: Invest in comprehensive training so everyone, from admissions counselors to faculty advisors, can effectively use your CRM to support student success.

Example: GSU’s Student Success 2.0 initiative includes implementing an enterprise CRM for a unified student record and early-alert triggers to boost retention by up to 1.2 % annually, with the National Institute for Student Success (NISS) also set up to that effect.

Source: GSU Student Success 2.0 Initiative

Creating a Culture of Success: A Holistic Approach

The most effective approach to student success blends marketing insights, CRM capabilities, and human connections in one big package. With these elements working in harmony, institutions can create environments where students from all backgrounds can thrive.

Remember that behind every data point is a student with dreams, challenges, and unlimited potential. When you align marketing, technology, and support programs around a student-centred vision of success, you can get positive outcomes in return. We don’t just improve statistics, we transform lives and fulfill higher education’s fundamental promise.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question: What is the definition of student success?

Answer: The definition of student success encompasses building communication skills and critical thinking activities, career or grad school readiness.

Question: How to measure student success in higher education?

Answer: While this question has intrigued higher educational professionals for decades, today’s schools are finding the right answers by combining traditional metrics and emerging indicators.

Question: What is a student success class in college?

Answer: It’s a course designed to help students be successful in college. It aims to help students properly navigate both academic requirements and college culture.