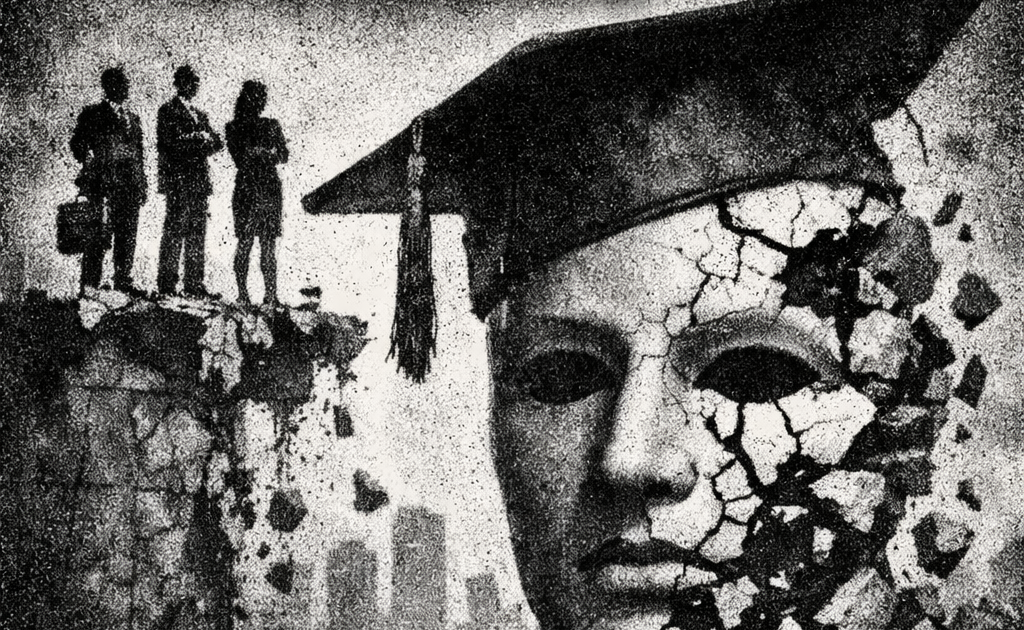

“The Merit Ladder”

You unlock the door to a university, and the corridor stretches infinitely upward. Every student walks the same stairwell, one step at a time. The walls are adorned with clocks, calculators, and grade sheets, ticking and tallying as if the universe itself measured effort with perfect fairness.

But something is wrong. Some students float effortlessly upward, their steps silent, their progress smooth. Others stumble on invisible obstacles, their feet dragging in ways the rules do not explain. They glance at the walls, at the clocks, at the calculators—every metric insists they are equal, every announcement proclaims fairness. Yet the disparity is undeniable.

A voice echoes from the ceiling, calm, clinical: “Merit is universal. Merit is measurable. Merit is scale-invariant.” The students nod, forced to believe, even as they watch their neighbors leap ahead. Some students whisper, “It’s not the merit—it’s the ladder.” And indeed, the ladder is uneven, its rungs hidden, shifted by invisible hands of wealth, culture, geography, and health.

In this world—the stairwell of American higher education—the illusion of fairness is maintained with meticulous care. But every so often, a student notices the truth, and then the voice falters, the clocks pause, and the corridors ripple with the secret that can no longer be hidden. For the myth of meritocracy is collapsing. The ladder was never fair, and now, as the illusion fades, everyone will see it.

The Scale-Invariance Claim

For more than a century, American higher education has rested on an elegant but unspoken assumption: that the rules of meritocracy are scale-invariant. The ideology promises that any student—regardless of wealth, geography, culture, family background, or health—can climb the credential ladder. A student from a low-income rural household competes on the same metric as a student from an affluent suburb. A community college student is measured by the same ruler as an Ivy League undergraduate. Merit, the story goes, is constant across all scales.

This is the deep mathematical promise embedded in the system:

(X, merit) ≅ (X, λ·merit) for all λ > 0.

Change the scale—money, social capital, proximity, cultural background—and the metric of “merit” supposedly remains unchanged. Hard work is invariant. Ability is invariant. The measurement of learning is invariant.

But no part of this has ever been true. To understand the experience, one could step into Kafka’s The Trial, where invisible, arbitrary rules govern the fates of all, or into the unsettling dimensions of The Twilight Zone, where a carefully maintained illusion of fairness masks structural control. Episodes like “The Obsolete Man” or “Number 12 Looks Just Like You” illustrate societies where uniform rules are proclaimed but inequities are baked into every interaction—a perfect mirror for the fiction of meritocracy.

The Characteristic Scales American Higher Ed Pretends Not to Have

Every foundational element of U.S. higher education has a characteristic scale. Once these scales are made visible, the meritocratic myth dissolves.

Financial scale.

With little money, a student cannot attend or persist. With substantial wealth, barriers disappear. Financial rescaling completely changes outcomes.

Social capital scale.

A family with generations of college experience confers knowledge, networks, and expectations that directly affect admissions, persistence, and post-graduation trajectories. First-generation students navigate blind. The system is not invariant under social capital rescaling.

Geographic scale.

Proximity to selective universities, high-performing high schools, or robust community college systems radically alters opportunity. Rural and small-town America operates at a completely different scale.

Cultural and linguistic scale.

Students whose home culture mirrors academic expectations “fit.” Students from culturally distant communities must perform costly translation work. This is not a scale-invariant environment.

Health and disability scale.

Students without health barriers move cleanly through the system. Students with disabilities or chronic illness face friction at every stage. Their outcomes follow a different curve.

A genuinely scale-invariant system would show consistent outcomes across all these starting positions. American higher education shows the opposite. The system has always been scale-dependent—and merit was never the dominant term.

The Measurement Problem the Meritocracy Never Solved

The ideological foundation requires not only a scale-invariant world but a scale-invariant measurement system. GPA, grades, test scores, papers, and degrees must reliably track some underlying construct called “merit” or “learning.”

Higher education never developed such a construct. “Learning” is not stable across institutions or contexts. It is socially constructed daily by instructors with different philosophies, different constraints, and different biases. There is no psychometric framework that defines a scale-invariant measure of learning. The closest attempts—standardized testing regimes—have repeatedly collapsed under their own inequities.

Yet the system pretends that a 3.8 at an Ivy and a 3.2 at a regional university reflect a universal metric rather than two entirely different grading cultures.

Grade Inflation and AI Cheating: The Mask Slips

Recent trends expose how fragile the entire measurement fiction has become.

Elite universities give A grades at unprecedented rates. Two-thirds of all grades at some institutions are now A’s. GPA averages well above 3.7 are defended as “signs of excellence,” but in practice they are rescalings of the ruler itself. Institutions under competitive prestige pressure simply adjust the metric to protect their reputation.

AI cheating accelerates the collapse. Students with resources buy tutoring, editing, and AI-powered writing tools. These tools outperform human novices. The ability to “perform merit” is now directly purchasable. The metric no longer measures writing ability or analytical thinking. It measures access to technology, coaching, and time.

The function of grades has shifted from signaling ability to signaling socioeconomic positioning. What was once ρ(ability) is now ρ(ability + money), with wealth as the dominant term.

Literary and Cultural Parallels

This collapse is eerily familiar in literature and media. Kafka’s The Trial captures the experience of navigating opaque rules that punish effort unpredictably. Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984 show societies that insist on fairness while structurally enforcing inequality. Ellison’s Invisible Man exposes the consequences of climbing a ladder rigged by invisible scales.

The Twilight Zone dramatized these dynamics for mass audiences. Episodes such as “The Obsolete Man”, “Number 12 Looks Just Like You”, and “The Shelter” depict societies where declared rules are universal, yet outcomes are determined by hidden advantages. These narratives echo the experience of students forced to believe in meritocracy even while the structural scales—wealth, family education, geography, culture, health—determine success.

What “Never Was Meritocratic” Actually Means

When HEI reports that American higher education never was meritocratic, it is not a moral accusation. It is an empirical one. The system was constructed with characteristic scales baked in. Wealth, social capital, proximity, culture, and health have always determined trajectories.

The ideology of merit obscured those scales by promising invariance where none existed. The promise served to justify gatekeeping, tuition inflation, credential inflation, and systematic exclusion. Legacy admissions, donor influence, geographic disparities, and familial educational background were not aberrations—they were structural pillars.

The Collapse of the Meritocratic Narrative

The contemporary system is unraveling because the myth of scale-invariance—its core ideological justification—has been exposed as untenable.

Grade inflation reveals that institutions adjust the metric to preserve prestige.

AI reveals that performance can be outsourced or purchased.

Credential inflation reveals that degrees are required because employers have no alternative signal—not because the degrees measure anything.

Homeschooling and private micro-schools reflect widespread disbelief in the system’s ability to measure learning.

Employer skepticism shows that the labor market no longer trusts the bachelor’s degree as a signal.

Once the legitimacy of the metric collapses, the legitimacy of the entire structure collapses with it.

The Devastating Implication: A System Built on a Mathematical Fiction

A truly scale-invariant system would show no significant correlation between wealth and degree attainment, no legacy effects, no geographic disparities, and no demographic patterning. The opposite is true in every dimension.

This system is not failing to fulfill its meritocratic promise. It never could fulfill it. It was designed for scale-dependence and shielded by the promise of scale-invariance.

Now that the mask is slipping, the $80,000 price tags, the exclusionary admissions processes, the credential inflation, and the crushing student debt load are losing their ideological justification. Without the fiction that merit is meaningfully and consistently measured, the system’s rationale dissolves.

The crisis of American higher education is not primarily a financial crisis or a demographic crisis. It is a legitimacy crisis. The foundational myth—meritocracy as scale-invariance—has collapsed. And with it, the justification for the entire credentialing apparatus is beginning to collapse as well.

Sources

Higher Education Inquirer archives on grade inflation, admissions inequities, and credential inflation.

John Beach’s work on the social construction of “learning.”

HEI reporting on AI cheating, K-12 system collapse, employer distrust, and the shifting meaning of academic credentials.

Franz Kafka, The Trial

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

George Orwell, 1984

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Twilight Zone episodes: “The Obsolete Man,” “Number 12 Looks Just Like You,” “The Shelter”