Across the UK, the sector is focused on scaling up wellbeing provision for students.

But as the mental health needs of learners increase, so too does the invisible pressure placed on academic and professional staff.

It’s a quiet crisis: wellbeing support for students is climbing the strategic agenda, while support for those delivering that care remains comparatively under-resourced. This is thrown into sharp relief given the turbulent times across the higher education institutions with staff facing uncertainty about stability of jobs, expectations and workload.

Staff as emotional first responders

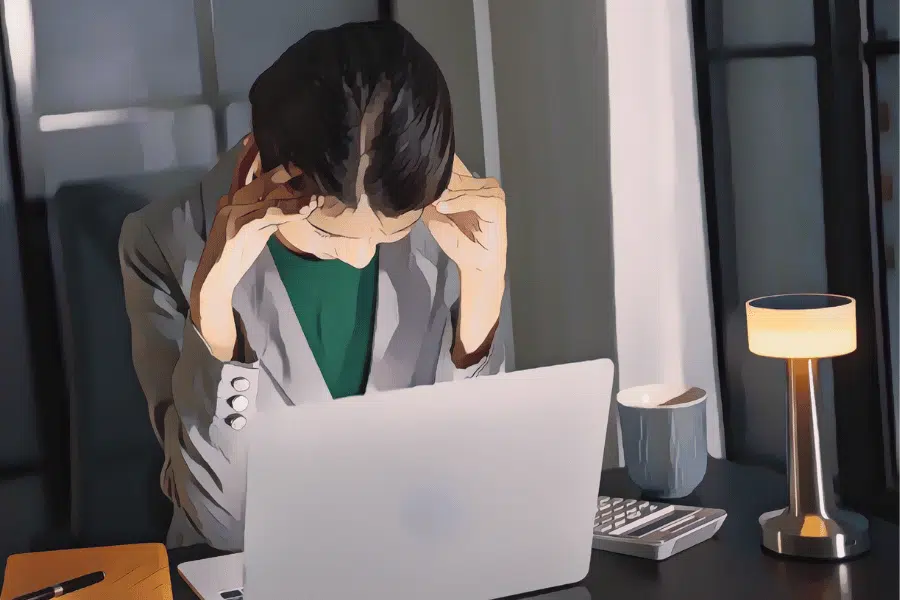

Within the current HE model, academic staff are expected to be responsive to student disclosures, emotionally available during distress, and flexible with academic adjustments, all while fulfilling the core responsibilities of curriculum design, delivery, and assessment. As a result, the boundaries between rising workload, pedagogy, pastoral care, and crisis navigation are becoming increasingly blurred. A 2022 report by Education Support found that 78 per cent of academic staff felt their psychological wellbeing was less valued than productivity, and over half showed signs of depression.

While professional staff often serve as key facilitators of institutional wellbeing initiatives, they too experience compassion fatigue and rising burnout especially in roles that bridge student-facing services and policy implementation. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on academic and professional services staff was far reaching, with an increased demand for staff to re-design teaching resources, master new technologies and approaches to engage students and support their wellbeing whilst also managing their own mental health and resilience.

Reorganising workload and investing in their wellbeing is a necessity for retention, effectiveness, and staff morale.

Coaching as a holistic practice of care

Coaching in higher education is a personalised approach for investing in an individual by supporting them to reach their full potential. The way coaching approaches support for an individual is through reflection, clarify goals, developing a growth mindset and build self-awareness. Therefore, coaching has been increasingly introduced across the higher education institutions for supporting students’ resilience. As those initiatives progressed, a parallel narrative emerged “Look after the staff and staff will look after students” in the 2022 Journal of Further and Higher Education by Brewster. Academic and professional colleagues also needed a space to pause, reflect, and rebuild their own sense of clarity and confidence.

Just as students have had to navigate the difficulties and emotional toll of the Covid-19 pandemic, so have staff had to navigate profound disruption in their lives whilst still providing support for students’ mental health. With the disruption caused by the pandemic only a few years in the past, staff now face more challenges resulting from job uncertainty, institutional restructuring, and sector-wide instability. The cumulative impact of these pressures has left many staff navigating blurred boundaries, depleted confidence, and a loss of clarity about their professional identity. In this context, coaching for staff focused on wellbeing, self-reflection, and self-compassion is a strategic necessity for supporting staff resilience.

Coaching sessions embedded into staff work plans would provide spaces for staff to decompress and have meaningful conversations to clarify career goals. While it may be desirable to reduce workload, coaching can have indirect effect in equipping staff to manage workload more efficiently through reprioritisation. Consequently colleagues would not only feel better equipped to support students but would also be able to recognise and respond to their own emotional needs, re-align work plans with their personal and professional values enhancing their overall mental wellbeing.

Coaching isn’t just a tool for student development, it’s a strategic investment in staff wellbeing. It’s also a reminder that institutional care must be available to all staff. As it stands right now coaching is reserved only for those in leadership management. All staff academic, professional, and operational deserve access to coaching as a tool for personal and professional wellbeing. When coaching is inclusive, it becomes a strategic lever for culture change, not just individual development.

Reframing the culture

In a sector often reliant on institutional employee assistance programmes or crisis-oriented interventions, staff coaching offers preventative, community-driven professional development that builds collective capacity for resilience. It reframes wellbeing not as “self-care,” but as cultural care embedded in day-to-day practice, mentoring, and reflection especially given the challenges of current circumstances.

In an age increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence and automated systems, the need to preserve human connection, emotional intelligence, and identity within education has never been greater. Coaching provides space to foster not just personal and professional growth, but a grounded sense of self, anchoring staff in their purpose and values in a period of rapid technological change. We cannot afford to treat staff wellbeing as secondary to student success as they are interdependent. When staff are supported, resourced, and cared for, they are better positioned to create the conditions in which students can thrive.

If the higher education institutions wants to retain engaged, resilient and emotionally intelligent educators, then coaching shouldn’t just be something we only offer to students and leadership staff. Leadership plays a critical role in setting the tone for this culture, ensuring that wellbeing is not just encouraged but embedded in everyday practice for all staff. It requires visible leadership commitment to wellbeing, through coaching, open dialogue, and consistent reinforcement of values of empathy, inclusion, and respect. One powerful way to enact this commitment is through institutionally supported coaching not just for leaders, but for all staff.

Many institutions already have a valuable but underutilised resource; trained internal coaches. These individuals bring deep contextual understanding of the higher education institution itself. Encouraging and enabling internal coaches to work with staff across all roles not just those in leadership can embed a culture of care and reflection at scale. When coaching is normalised as part of everyday professional development and wellbeing, it signals that the institution values its people not just for what they produce, but for who they are.