When Jake Winston began looking at colleges in fall 2019, he was primarily looking at public colleges in his home state of North Carolina, as he felt those would be the only institutions he could afford. He was interested in Washington & Lee University, in Virginia, due to its location—far enough for a change of scenery, but not so far he couldn’t visit home—and its rich and complex history. But he didn’t think he could afford the high price tag.

At a presentation by admissions officials, though, he learned about the W&L Promise, which covers the full cost of tuition for all students whose families fall into a specific income bracket. Once he got his aid offers back from colleges, WLU was the obvious choice, costing him just $5,000 annually, a sum that he paid out of pocket using money he made from summer research jobs.

“Being able to know I was going to graduate debt-free from the start allowed me to pick what I was passionate in, and that’s teaching, which is not the highest-paying role in the country,” said Winston, who now teaches seventh-grade history in Northern Virginia. “But it is what I wanted to do with my life.”

WLU has one of the oldest tuition-guarantee programs in the country. It launched in 2014, offering free tuition to students whose families make less than $75,000 each year; now, that number has surged up to $150,000, and students whose family income is less than $75,000 also get free room and board.

Since then, more and more colleges—especially, but not only, selective private institutions—are offering completely free tuition to students whose families fall under a certain income threshold. Nowadays, that maximum is typically $100,000 annually, an income bracket that includes about 57 percent of U.S. families as of 2024, according to an analysis by the Motley Fool. But some have expanded the offer of free tuition to those whose families make as much as $200,000, encompassing all but 16 percent of American households. (Most programs also require the families to have typical assets, and some are only open to in-state students.)

In the past year alone, a slew of universities has announced new free tuition programs or expanded their existing programs, including Wake Forest University, Reed College, Emory University, Macalester College, Tufts University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University and Lasell University.

Administrators at more than half a dozen institutions with promise programs told Inside Higher Ed that they hope that the move will attract low-income students who didn’t realize how financially accessible higher education, even at expensive institutions, can be. It’s also an effort to improve cost transparency—an area that has frequently come under scrutiny as the actual cost of college has become increasingly obscured by scholarships, aid, fees and books and other indirect costs.

Breaking the Cost Barrier

For many institutions offering tuition guarantees—also called promise programs—it’s more of a change in rhetoric than in actual financial aid policy.

Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, for example, announced a program last November guaranteeing free tuition for students with family incomes under $75,000 and promising those with incomes under $100,000 wouldn’t have to take out any student loans to access a CMU education, beginning with the incoming class in fall 2025. But according to Brian Hill, the university’s associate vice provost for student financials and enrollment systems, that’s how the university had already been quietly operating since 2016.

“In truth, it was to make sure that prospective students knew that CMU was an affordable option for them. That was the primary reason,” he said. “We’ve been saying that we met full demonstrated financial need for our students … [but] a barrier we don’t know if we’d gotten through or not is students that would look at the sticker price [of $67,020 per year] and just completely write CMU off before they even explored it.”

The surge of these programs comes amid concerns about the growing cost of higher education and that the return on investment of a bachelor’s degree doesn’t warrant the seemingly exorbitant cost; a few institutions in the U.S. now have a sticker price upward of $100,000 a year.

At the same time, experts argue that the price of higher education has actually gone down when accounting for inflation and the high rate of aid students generally receive. For several decades, higher education has followed a model in which institutions advertise a high cost of attendance but a significant number of students receive large scholarships. This approach helps to make higher education look like a luxury product while students and families feel like they’re getting a good deal. But that strategy has come to bite institutions in the butt, according to W. Joseph King, former president of Lyon College and a higher education consultant, as many low- and middle-income students now feel the high cost of college makes an education unattainable.

“What this led to was almost like an arms race of rising stated tuition numbers and a fall in net tuition numbers. All sorts of groups, including the federal government, have been trying to get to numbers that are more reflective of the actual cost,” he said.

Promise programs aim to change that narrative by showing low- and middle-income families that getting an education even at a seemingly pricey school can be achievable.

Colleges have made other attempts to communicate that message to students and parents. That includes developing net price calculators, which often show that low-income students would be paying just a fraction of the sticker price, or announcing that their institution is able to meet all of a student’s demonstrated financial need—a number based on a federal student aid formula that determines how much a family is able to pay.

But many families have no idea what demonstrated financial need means or are unaware of net price calculators, enrollment professionals say. Simply saying that an institution offers free tuition can be the ultimate tool for price transparency, according to Milyon Trulove, vice president and dean of admission and financial aid at Reed College, which announced plans to expand its regional promise program—currently available only to students in Oregon and Washington—to all students with family incomes under $100,000 in 2026.

The institution also has a net price calculator, he said. But if presented with both that calculator and the promise of free tuition, the latter will immediately be meaningful to students, whereas the former won’t.

“[Students] say, ‘This makes sense to me, today, right now … and now I can listen to all the other stuff about fit and anxiety about money is no longer in the way of me fully participating in the college admission process,’” he said.

Along with institutions offering free tuition to any student who fits within a certain income bracket, even more institutions offer tuition guarantees to students based on grade point average or for transferring from a local community college system.

‘Rigorous Financial Planning’

Most of the university officials who spoke with Inside Higher Ed said that their institution was in a very strong financial position and able to afford to support so many students because of large endowments and generous donations, including fundraising specifically aimed at increasing student aid.

From 2016 to 2024, Carnegie Mellon, for example, increased its undergraduate financial aid budget 86 percent.

“We truly made a massive commitment to making affordability a real thing at CMU,” said Hill. “I think we’re in a very positive position in terms of finances, but it took a lot of commitment from … executive leadership to make this a priority.”

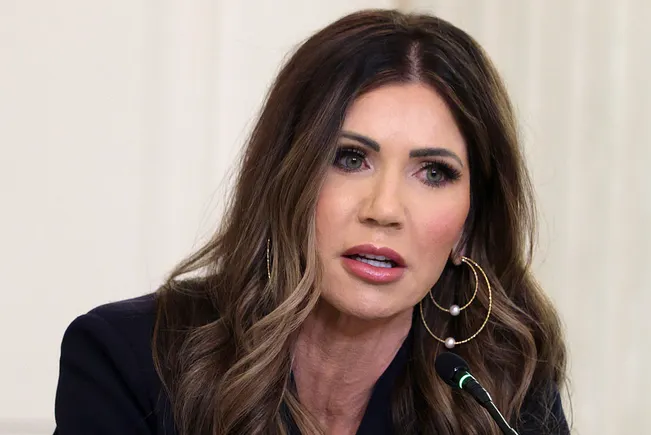

Wake Forest, which announced last week that it will offer free tuition to all North Carolina students with family incomes below $200,000, is one of the few schools that said that its promise program, called the North Carolina Gateway, would substantially increase the total amount of aid it gives out. President Susan Wente said that, similarly to CMU, the funds for the initiative come in large part from a massive fundraising effort that has raised over $150 million for financial aid since 2022.

“This involved rigorous financial planning and analysis and knowing we could meet the commitment, should we announce it,” she said.

But not every university with a promise program is leaning on massive donation campaigns. Radford University, a public institution in Virginia, was able to begin offering free tuition to all students from Virginia with incomes below $100,000 simply because of the ample amount of funding it gets from the state, according to Dannette Gomez Beane, vice president for enrollment management and strategic communication.

Virginia tends to be generous toward higher education, Beane said, but the two regional public universities in southwest Virginia, which has the lowest college-going rate of higher education of any area in the state, receive the most funding. That’s what allowed Radford to begin its promise program, which the institution promoted heavily in the 60-mile radius around its campus, in 2024.

“With all things higher ed and higher ed financial aid, not everything is sure, and we’re learning that this year more than ever,” she said. “I think that state funding, federal funding—if you have models that are dependent on those, you have to constantly be adjusting your models … there is that vulnerability, but we’re just gracious that we’ve had favor with the state.”

Boosting Low-Income Enrollment

Although many of these programs are new, those that have been around for multiple years have seen positive results. At Washington & Lee, Sally Richmond, vice president for admissions and financial aid, said that there have been massive jumps in enrollment of rural students, first-generation students and Pell-eligible students since she joined the university in 2016.

It’s impossible to say whether those changes can be attributed specifically to the university’s promise program, she noted. But, she said, “our financial aid office, who is certainly on the front line of having these conversations along with our admissions team, speaks to the fact that this concept of the promise is the one that resonates most with our prospective students and families.”

Reed College, similarly, saw a 25 percent increase in middle-income students in its program’s first year, during which it was only available to students from Oregon and Washington.

Wente, Wake Forest’s president, said she is eager to see how the university’s newly announced tuition guarantee program will impact low- and middle-income enrollment.

“As a scientist myself, we’re going to pilot this, look at its impact, look at how we can ensure that it’s really achieving what we hope in terms of offering students greater access,” she said. “In terms of the middle and lower income bands, those are the students who often don’t have as many options. So, how do we give them as many options as possible?”