Before the Department of Education laid off half its staff in March, college financial aid officers on the west coast could typically help a student track down their missing login information for the federal aid application in a matter of minutes.

But now, due to limited hours of agency operation, tracking down a student’s Federal Student Aid ID can take days or even weeks; an east coast-based help line, which used to be open until 8 p.m. now closes at 3 p.m.—or noon Pacific time, according to Diane Cooper, the senior financial aid officer at Northwest Career College in Las Vegas.

For Cooper, the reduction in force has upended countless advising sessions and made it difficult to enroll working adult learners with tight schedules.

“When I have a student who’s driven 30 minutes to get here and then we have this issue, I can’t do anything,” Cooper said. “When they did this reduction, I don’t think they thought about colleges on the west coast.”

Over the past three months, the financial aid office at Northwest has tried to be proactive and warn students about retrieving their username and password in advance, but not everyone gets the message in time.

“When [prospective students] face a roadblock, it’s very frustrating,” Cooper said. “I’ve even had some people say, ‘Well, college just must not be meant for me.’”

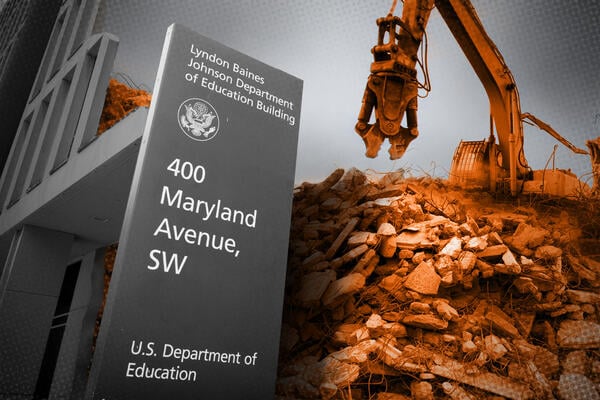

Difficulties applying for financial aid are just one of the many road bumps students and university staff across the country have faced since Education Secretary Linda McMahon and the Department of Government Efficiency cut the department down to just over 2,000 employees—about half of what it was during the Biden administration.

The Department of Education told Inside Higher Ed that all three of its help lines, the Federal Student Aid Information Center, FSA Partner School Relations and the FPS Helpdesk were open well past noon Pacific time.

“Just within President Trump’s first six months, the Department has responsibly managed and streamlined key federal student aid features, including fixing identity verification and simplifying parent invitations, while ensuring the 2026–27 FAFSA form is on track,” said deputy press secretary Ellen Keast.

But Cooper said ever since the reduction in force if she calls FPS in the afternoon they are closed.

Since March, colleges, advocates and others have noticed lags in communication about financial aid. Between March 11 and June 27, the department also dismissed more than 3,400 civil rights complaints—an unprecedented number, according to one former official. Additionally, the department ended an IPEDS training contract, among other changes at the Institute for Education Sciences, sparking concerns about the future of data collection at the agency.

Some college administrators expressed optimism that the staff shortage would be temporary after a district court blocked the layoffs in May. But the Supreme Court extinguished that hope last week when it overturned the ruling, giving McMahon the go-ahead to proceed with the pink slips and other efforts to dismantle her agency.

Now, higher education experts are adjusting to the reality of a smaller department for potentially years to come.

“It’s a whole lot easier to break things than it is to put them back together again,” said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education (ACE).

He and others worry that the department’s deficiencies will only get worse as staffers rush to overhaul the federal student loan system and implement other policies in the Big Beautiful Bill over the course of the next year. Add to that President Trump’s plan to dismantle the department by transferring certain programs to other agencies and what you have, Mitchell said, is “a mess.”

“I suppose we all need to adopt a ‘time will tell’ philosophy about this,” he said. “But I for one am not optimistic.”

Keast, on the other hand, said the department is complying with court orders and fulfilling its statutory duties.

“We will continue to deliver meaningful and on time results while implementing the President’s [One Big Beautiful Bill] to better serve students, families, and administrators,” she said.

Behind the Scenes ‘Breakdown’

Cooper and Northwest Career College are not alone in struggling to get help from the Federal Student Aid Office. Nearly 60 percent of colleges and universities experienced noticeable changes in agency responsiveness or processing delays, according to a survey conducted by the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators in May.

While 48 percent of respondents ranked front-facing glitches that directly affect students as their top concern, Melanie Storey, NASFAA’s president and CEO, noted that the Free Application for Federal Student Aid and aid distribution have been operating relatively smoothly. Many of the challenges created by the reduction in force, she said, are actually taking place behind the scenes.

Nearly half of the institutions surveyed said that the FSA regional office they reported to had closed, and about a third said they were experiencing gaps in support as a result. Applying for the financial aid eligibility of a new program or addressing compliance concerns was already difficult before the regional offices closed, said Storey, who worked at FSA during the Biden administration. Now it will be even more arduous.

“Our communities are just not getting answers to questions that they have,” she explained. “But if we see a breakdown in that work, we will see a breakdown in the delivery of aid.”

Paula Carpenter, the director of financial aid at Jefferson College, a community college in eastern Missouri, said the biggest unknown is whether she will be able to complete the college’s recertification before the September 30 deadline and maintain its eligibility for federal aid.

In the past, when it was time to begin the recertification process, Carpenter received an email from staff at the FSA Kansas City office, which was one of eight that closed in March.

Now, “I’m uncertain on when I should submit the application, how long it’s going to take, and the impact it will have on other changes along the way,” she said. “The loss of those working relationships we had with the Kansas City participation team is definitely creating a lot of uncertainty.”

Although critics have accused DOGE of operating in a rash and haphazard manner, one senior FSA official told Inside Higher Ed that the decision to cut staff at the regional offices that handled eligibility and compliance was likely deliberate.

“The easiest place to cut is in functions that the broader public doesn’t see, even if they may be impactful,” said the official, who requested anonymity to speak freely. “You can’t cut the FAFSA … and you can’t cut the teams that support the actual technology for dispersing aid and handling repayment, because then borrowers start calling the press and calling Congress,” they added. “But if it just takes longer for schools to go through the process, get questions answered and get support then there’s not a discrete pain.”

But just because the pain may not be publicly distinct, that doesn’t mean colleges aren’t feeling it.

“There’s never been a worse time to be starting or renewing a Title IV program, and there’s never been a better time to be not following Title IV regulations,” the staffer said.

Future of ‘Flying Blind’

Other concerns raised by higher education advocates are more focused on the future.

The sweeping Big, Beautiful Bill, signed into law July 4, includes a swath of higher education policy changes, ranging from revamping student loan repayment plans to introducing a novel accountability metric for colleges. Getting those changes implemented by July 1, 2026 with fewer employees is a tall order for the department, and many higher education advocates worry that the agency will struggle to pull it off.

Mitchell from ACE fears that a general lack of data will hamper efforts to implement the new policies. The Institute for Education Sciences, an agency focused on collecting and analyzing education data to inform policy, was almost entirely gutted by the layoffs. Fewer than 20 employees remain, down from more than 175 at the start of the year, according to the Hechinger Report. The National Center for Education Statistics, one of the most crucial arms of IES, is down to just three staff members.

Without IES fully staffed, Mitchell worries colleges and universities will be held to new student outcome standards based on inaccurate data.

“Who will be on the other side receiving information about program level earnings? We don’t know,” he said, referring to the new post-graduation income test that colleges will have to pass. “If the cuts go through the way they are planned, higher education will largely be flying blind. We won’t know what programs and interventions will work to improve student success at the very moment when higher ed is facing a crisis of confidence about whether it is doing the right thing for students.”

Without the department, colleges will have to increase their own technical capacities, he added, and that comes at a cost.

The department acknowledged that the bill includes major changes to the federal student aid system and the development of a new accountability program but said that, with billions of dollars in federal funding, the Office of Federal Student Aid will be able to complete both projects.

More disruptions are expected at the department in months to come as the Trump administration aims to shift certain responsibilities and programs to other agencies. Last week, shortly after the Supreme Court ruling, McMahon formally announced a plan to move career, technical (CTE) and adult education programs to the Labor Department. Trump and other officials have also talked about moving the federal student loan program to either the Small Business Administration or the Treasury Department.

But the FSA official said the department is using the transfer of smaller CTE programs as a test run first and will take its time to move the federal aid system—if it does at all. The official is also confident the department will be able to put the new policies and programs in motion, but only if Congress extends the deadlines.

“I think there’s a wide recognition, including on the Hill, that the timelines in the bill aren’t realistic,” the official said. “I feel good about being able to get [it] done … [But] if the question is, can we hit all the details and all the timelines? I think that’s impossible.”

Both the department staffer and Storey from NASFAA said that if lawmakers and White House staff are smart, they will apply the lessons learned from the last time FSA overhauled student aid programs. For the Biden administration, pressure to finish a big project in a short amount of time, combined with a lack of feedback from college leaders, led to a botched rollout of the new financial aid application, they said. Hopefully, this time things will be different.

“If we learned anything from the FAFSA debacle, it was that while the department was struggling to get their implementation in order, they neglected institutions and vendors who are incredibly important partners in that ecosystem of delivering aid,” Storey said. “Let us not make that mistake again. Ignore the role of institutions, at your peril. They are the front lines.”