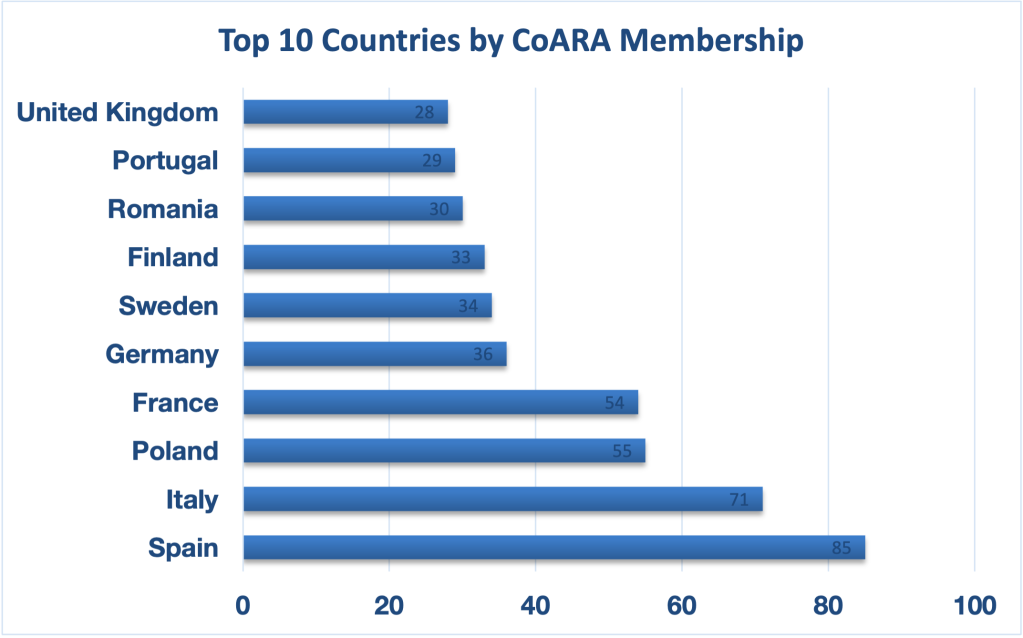

The standout headline stat in this year’s HEPI/Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey (SAES) is that there’s been a dramatic rise in the proportion of students at work.

Full-time undergraduates undertaking paid work (that is not related to their course) during term time is now at 68 per cent, up from 56 per cent in 2024 and just 35 per cent a decade ago.

![]()

That’s tempered a little by the news that of those in work, the average number of hours worked during term time has actually fallen a little – from 14.5 hours to 13.1 hours. The report speculates that some of those who have begun working in the past year may have taken jobs with more moderate, perhaps more manageable, hours.

Or maybe – in an era when the leisure and hospitality industries are on their knees, and employers have been grappling with a minimum wage rising much faster than inflation, students are struggling to get the hours they need.

Either way, if we extrapolate up the sample and the overall mean average, and assume that students are roughly accurate in their responses, there’s an even more astonishing stat buried in here:

![]()

That’s right – student numbers over the decade are up 15.5 per cent, while the total hours worked in term time are up 79.6 per cent.

There’s a touch of numberwang here – so to put the numbers in some vague context, full-time students in the UK working during term time are now contributing over a quarter of the hours that Latvia’s entire workforce produces in a full year.

Paid employment can be positive for all sorts of reasons – but the idea that an increase like that won’t be having serious negative impacts on health and learning really is for the birds.

If – as various aspects of this year’s SAES suggest – earning while learning is a “new normal”, the least students should expect is universities developing proper strategies to facilitate it, and the government providing a proper framework to enable it. On European comparisons, we’re miles away from both.

This is, as ever, a weighty bit of work – 10,232 full-time undergraduate students in the UK, representing a population of 1,759,245 (2023–24 data) all yield a margin of error of ±1% at a 95% confidence level.

That said, a health warning before we get into it – while the figures weight the sample for ethnicity, type of school attended, discipline and (for the first time) domicile, they don’t weight the sample for age.

And given the 22-25 age group has nearly doubled from 18 per cent to 36 per cent of the sample year on year, while the 26+ group has collapsed from 23 per cent to just 5 per cent, a pinch of salt is required throughout.

Various of the questions referred to below can be interrogated for a range of demographic and other splits via the cross-tab tables, which DK has plotted here.

[Full screen]

Short-lived celebrations

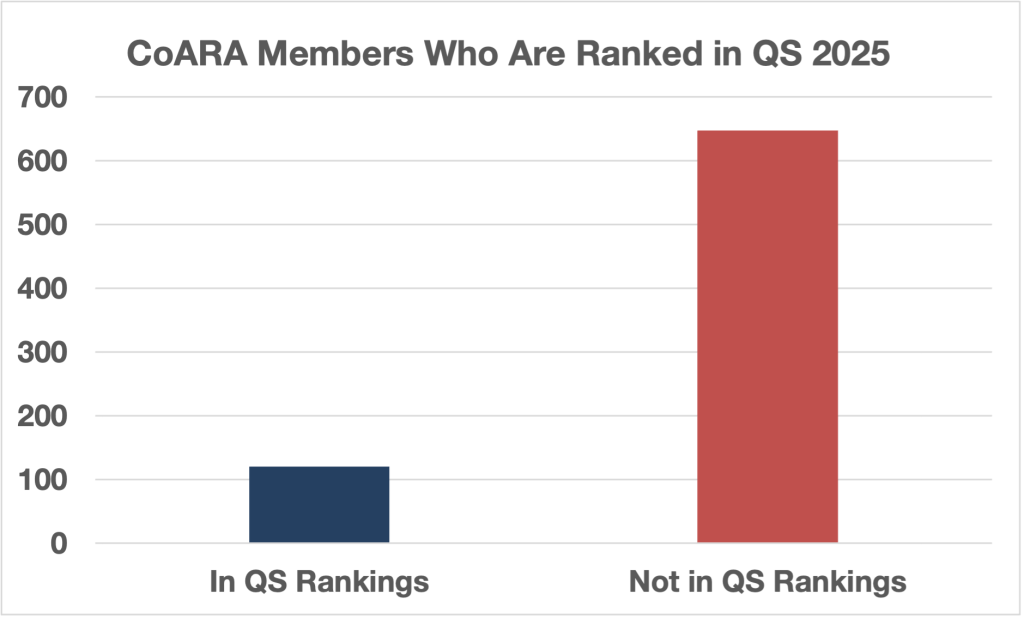

Corks were popping last year when the headline “value for money” perception score rose after its Covid collapse to 39 per cent. Short-lived celebrations, sadly – we’re back down at 37 per cent feeling they received good or very good value.

![]()

As ever, Scottish students perceive the highest value, although even then only at 48 per cent – a figure which always baffles some on the socials who forget that a bargain Ryanair flight to Reykjavík still feels like terrible value if your sandwich and coffee at Keflavik International costs double that.

That’s borne out in the factors considered when judging VFM data – cost of living is some 10 percentage points ahead of any other factor. Tuition fees have declined in relative significance, academic quality concerns are also moderating, and stuff like one-to-one staff time, contact hours, and course organisation remain relatively stable but secondary.

![]()

Down in the splits there are some fascinating differences not picked up in the report – women, first in family and state educated students are less happy than peers, students in non-university halls are 10pp more likely to report poor value than those in university halls or living alone or at home, care experienced and estranged students are almost twice as likely to report poor value than their peers, and degree apprentices are 11pp more likely to report poor value than UGs.

This is your regular reminder that an apprentice aged 21 in the first year of their apprenticeship is entitled to a princely minimum hourly rate of £7.55 an hour. Earn while you learn indeed.

One thing that’s striking is a kind of Value for Money paradox – there’s a very strong relationship between negative impact of the cost of living crisis and VFM perceptions, and a good value “sweet spot” of working 10-15 hours (4 in 10 happy), with those working fewer or more hours less happy.

I’d suggest we’re staring here at two “trapped” student profiles – those having to work so many hours that it’s ruining the experience, and those who need to work but are constrained by visa restrictions, health, lack of available employment, course demands or timetabling conflicts – leaving them financially stressed without the ability to address it.

Grating expectations

On expectations, bifurcation has been the big story in SAES in recent years – and this year’s no different. 26 per cent of students in 2025 report that their experience exceeded expectations – double the rate seen during the pandemic in 2021.

But there’s been a corresponding rise in students whose experience was worse than expected too – 15 percent in 2025, up from 8 per cent in 2021.

![]()

For students whose expectations weren’t met, it feels like time and money are the ones hardest to influence – 23 per cent cite less disposable income than expected, 18 per cent are taking on more debt than anticipated, and 17 per cent cite longer commutes.

Academic issues were up there too, though – poor teaching quality (23 per cent), lack of support for independent study (23 per cent) and course disorganisation (20 per cent) are the notables. Analysis of the qual also suggests that loneliness should have been a box they could tick.

And down in the splits there are some similar lessons to those seen in the VFM questions – again, only 18 per cent of those in non-university halls have had expectations met, over 10pp worse than those at home or living alone.

I’ve had a few

I’ve been following the “regret” question quite closely for a few years now – and I’m afraid to say that this year a record low of 56 per cent said they would make the same decision on course and university again. Significantly, those who would avoid higher education entirely has nearly doubled from 6 per cent to 11 per cent between 2024 and 2025.

The factors underpinning that are much better explored in the Nicola Dandridge/University of Bristol deep dive we looked at a few weeks back, although sticking out like a sore thumb here are those working but under 10 hours (just 38 per cent would make the same choice), those doing Level 4 or 5 quals (on 46 per cent and 40 per cent respectively), and those with caring responsibilities, those that are themselves care experienced, those estranged and trans students – they languish down on 44, 39, 40 and 41 per cent “no regrets” respectively.

![]()

Non-university halls also make another of their regular appearances – every other type of living arrangement averages out at between 55 and 59 per cent “no regrets”, while those in private PBSA are on 39 per cent. An astonishing 21 per cent of them would avoid HE altogether if they had their time again.

Considered withdrawing (roughly two-thirds) and the reasons for that (mental health and cost of living) both remain stable – combined with the regret figures, they continue to suggest that the system is better at trapping students onto a conveyor belt than anything else.

Can I have some more?

Every year students are asked to make qualitative suggestions on what could be done to improve the quality of the student experience – eight major themes range from requests for more personalised academic support and timely feedback to calls for enhanced mental health services, financial assistance, and improved teaching quality.

I won’t dwell on them here – suffice to say that almost all of them represent a direct collision between rising expectations and diminishing resources. Students are requesting precisely the kind of labour-intensive, personalised services that universities are routinely subjecting to “shrinkflation”.

Smaller class sizes, one-to-one interaction with staff, detailed feedback, enhanced mental health support, and reduced fees for international students all feel like things doing in precisely the opposite direction – a potentially vicious cycle where quality is hit, that generates further dissatisfaction. They are not necessarily completely unaffordable – but they either reflect support expectations associated with an expected speed of completion not seen in many other countries, or degree structures which pile on too much pressure unnecessarily.

That said, if you’re looking for something (anything) resembling good news here, it’s on aspects of teaching. Pretty much every characteristic tested – encouraged you to take responsibility for your own learning, clearly explained course goals and requirements, helpful and supportive, initiated debates and discussion are within margins of error at record satisfaction.

![]()

Assessment feedback has reached new heights, with holistic feedback and draft work feedback achieving record scores – over 15 percentage points higher than 2018 levels. And assignment turnaround times have dramatically improved – 61 per cent are now returned within two weeks (up from just 33 per cent in 2022), exceeding evolving student expectations where 70 per cent expect two-week returns.

Under pressure

The problems are in pressure and time. Contact hours are stable at 15-16 hours provided, 13 hours attended, but student satisfaction with contact hours has declined significantly by nine percentage points to its lowest level in a decade (excluding the pandemic blip).

The data reveal that students generally value contact hours, with those having 10+ hours weekly showing greater satisfaction, but the key factor seems to be the rise in students working for pay. Students without paid employment show notably higher satisfaction with contact hours (64 per cent) compared to working students (57 per cent), suggesting that increased work commitments are creating challenges in balancing total time demands rather than dissatisfaction with the contact hours themselves.

That pattern intensifies as students progress through their degrees, where they attend fewer contact hours while taking on more paid work responsibilities – and the decline appears linked to students’ difficulty managing their broader commitments, indicating a need for more flexible timetabling to help students balance their academic and work responsibilities effectively.

That all results in this fairly alarming chart – not only is the amount of time spent in timetabled hours and independent study at its lowest in half a decade (24.2 hours), there’s a significant difference between those who work and those who don’t.

![]()

Worse still, as I’ve noted before, the UK’s notional ECTS-to-hours ratio is already lower than the rest of Europe at 20 hours per credit (everyone else is on 25-30 hours) – these figures suggest that they’re somehow getting their degrees on 15 fewer hours studying than they’re supposed to be able to, all while being expected to complete 5.8 summative assignments per semester and 4.1 formative assignments – both at record highs.

The pressures of work, what is starting to look clearly like over-assessment, cost of living and so on – all in a system and culture set up to get UGs through their degrees faster than pretty much every other country – will almost certainly be generating support demands, mental health issues and (Al related) “efficiencies” that are harming students’ health and learning.

Hence wellbeing remains concerningly low, with only 14-18 per cent reporting high scores on key measures (life satisfaction, happiness, feeling worthwhile, and low anxiety) – half the levels seen in the general population. Students have very high, perhaps unrealistic expectations for institutional mental health support too – 40 per cent believe universities should provide comprehensive services including severe cases, and another 41 per cent expect preventative programs and counselling for less severe issues.

Students with existing mental health difficulties, those significantly affected by cost-of-living pressures, trans students, first-years, and those studying in Scotland show even higher expectations, with nearly half (47 per cent) of students with mental health challenges expecting comprehensive university support.

All about the money

Back on money again, three-quarters of students continue to report that cost-of-living pressures have notably impacted their studies, nearly one-in-five students have taken on more debt than planned (particularly affecting home students), and other impacts include reduced spending on course equipment, lower participation in sports and societies, and increased commuting costs.

![]()

The reduction in extracurricular activities is particularly worrying given existing student mental health challenges – and miserably, financial challenges mean that 6 per cent of home students selected a different course than they had planned to, and 7 per cent selected a different institution than they had planned to.

This year there’s also a strange set of questions testing students’ attitudes towards maintaining, increasing or decreasing tuition fee levels with some associated quality trade-offs – it’s not clear that that tells us much given the range of other factors underpinning their value perceptions.

Breaking points

So what are we to make of all that? Similar to previous years, the data suggests a system under extraordinary strain – but this year’s findings suggest to me that we’ve crossed a threshold from manageable pressure into systematic breakdown.

One way to understand what’s happening is through the lens of the Study Demands-Resources model we found in European student research. Eurostudent’s analysis distinguishes between stress-inducing demands (excessive workload, time pressure, financial obligations) and supportive resources (peer contact, teacher guidance, family support, adequate funding) – where wellbeing depends on the balance between these forces.

The SAES figures suggest we’re witnessing unprecedented demand escalation alongside systematic resource depletion. Students face more assignments per semester (up 47 per cent since 2017), their capacity to engage has collapsed, independent study time has fallen below contact hours for many subjects, and the employment reality means students are operating at 44.3 total weekly hours while UK full-time workers average 36.6 hours.

Another lens is Maslow. Universities are investing heavily in what I’ve previously described as self-actualisation interventions (creative assignments, intellectual debates, community building) while students struggle with basic physiological and safety needs. As I’ve noted before on here, when basic needs are unmet, higher-order educational experiences become impossible regardless of quality – and every extra hour of effort up the top of Maslow has diminishing returns.

The control paradox is also troubling. We’re used to universities being held accountable for outcomes – retention, belonging, wellbeing, satisfaction, completion – that are increasingly driven by factors outside their control. Universities might perfect contact hour delivery, but students working extreme hours can’t attend. They can enhance support services, but working students can’t access them during traditional hours. I’m usually the first to argue that universities should look at what they can control – but the multi-car pile up of issues inside that which they can’t is starting to look overwhelming.

Most troubling of all is what this all means for “full-time” study. Every student finance review and the credit system itself puts its meaning at 35 to 40 hours a week of academic work. 24.7 hours of actual academic engagement, with a record number of deadlines to hit is a 35 to 40 per cent shortfall. When “full-time” students operate at part-time academic intensity while longer hours than full-time employees, something has to give – their health, their wider intellectual and social development, academic integrity or all three.

I’m also starting to worry profoundly about choice, equality and institutional mission. Take the Russell Group’s recent home student expansion. These are universities predominantly located in expensive cities, increasing their numbers (but not necessarily proportions) from lower tariff applicants and lower socioeconomic backgrounds. The mathematics are cruel – poor(er) students recruited to institutions they cannot afford to attend properly, forced into extreme employment that excludes them from the very experiences that make those institutions valuable.

A two-tier system – where financially supported students engaging fully with campus life, relationships and opportunities, while “widening participation” students work 30-plus hours, miss relationship-building opportunities, and graduate with the same credentials but fundamentally different educational experiences. This isn’t inclusion, or positive choice – it’s a sophisticated form of educational inequality that maintains the appearance of social mobility while perpetuating class advantages.

On this evidence, the efficiency imperative – on both universities and students – is harming what makes higher education valuable beyond qualification acquisition. The slow elimination of intellectual curiosity, community membership, personal development, and critical thinking is what distinguishes higher education from job training. It’s melting away.

It all points at a need for much radical thinking than is on offer either in the SAES report’s recommendations or in the portfolio reviews and strategic collaborations being planned in documents like this. If nothing else, you can’t pull off a transformation and efficiency taskforce on provision without one looking at the student experience.

The UK does, on admittedly shaky OECD evidence, have a curiously expensive way of delivering higher education. Unless the sector is prepared to be more radical over curriculum design, subject specialisation, assessment and credit acquisition, and be matched in maintenance and flexibility efforts by a government prepared to own the problems its predecessor created, it will continue down a fatal path – of demanding more and more from staff and students while paying the former less and less and charging the latter (through commercial debt and lifetime repayments) more and more.