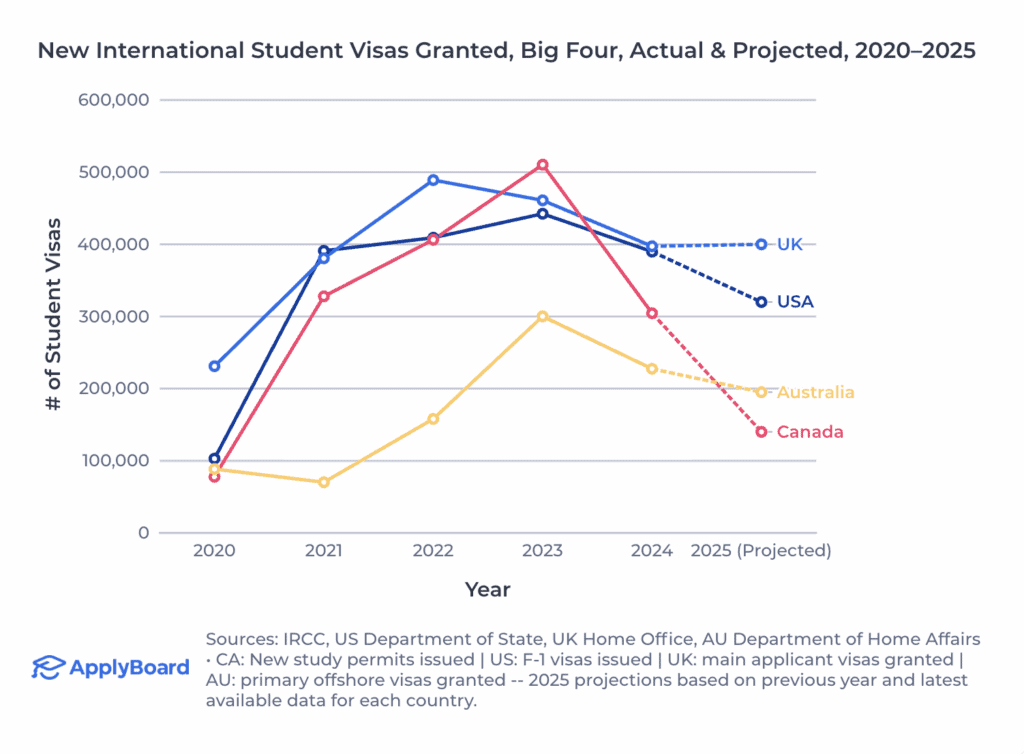

In my recent article for The PIE, I reflected on how Canada’s international education system has been moving through a period of turbulence and uncertainty, highlighting the compounding effects of the past several years, abrupt policy shifts, uneven communication, and ongoing immigration challenges that have created instability and eroded trust among students, families and global partners.

This second piece builds on that discussion. Canada’s international education sector continues to navigate a turbulent period, one that is reshaping how institutions, students, and communities make decisions today and plan for tomorrow.

Yet within this turbulence lies an opportunity: to chart a clearer, more deliberate path forward that restores confidence and strengthens Canada’s global role. There is no simple fix, but by examining how other countries and Canadian provinces have approached similar challenges, we can begin identifying the building blocks of a more stable, coordinated and sustainable strategy.

If Canada is to navigate this moment and rebuild stability and credibility, it must move beyond reactive decision-making. What is needed is a clear, long-term framework, one grounded in evidence, predictable investment, and collaboration across governments, institutions, employers and communities. Lessons from Germany, New Zealand and British Columbia demonstrate that more deliberate and sustainable approaches are not only possible, but necessary.

Lessons from Germany’s model

Germany provides a compelling example of how international education can be integrated into a broader national economic and demographic strategy. While the contexts differ, Germany’s constitutional division of responsibility for education between the federal government and the Länder is in many ways similar to Canada’s federal–provincial structure, making its approach worth examining. One important distinction is tuition: in most regions, international students pay minimal or no fees, reflecting a long-term view that the real return on investment comes from decades of workforce participation and tax revenue rather than short-term tuition income.

A 2025 study by the German Economic Institute, commissioned by the German Academic Exchange Service, found that the 79,000 international students who began degree programs in 2022 could generate between €7.36 billion and €26 billion in lifetime net fiscal gains for the public sector coffers. Even under conservative projections, public investment in international students pays for itself within two to five years after graduation. International graduates could offset up to 20% of Germany’s projected GDP slowdown due to demographic change over the next decade.

While Canada’s policy environment, tuition structures, and labour market integration differ, this illustrates what can be achieved with a coordinated national framework that aligns higher education with workforce needs.

A key part of this approach is the Campus Initiative for International Talents and the FIT program. These initiatives fund universities to prepare students for academic life, support their integration, and connect them with employers before and after graduation. They also invest in expanded career services, targeted retention programs and partnerships with industry to ensure smoother transitions into the labour market. Critically, this is made possible by predictable, multi-year federal funding, allowing institutions to sustain, refine and scale initiatives over time while sharing lessons across the sector.

New Zealand’s managed growth approach

New Zealand offers another instructive model, one that is still in its early stages but marks a shift from previous approaches. Following a period of post-pandemic recovery, the government launched the International Education Going for Growth strategy in 2025, setting a ten-year target to nearly double the sector’s economic contribution by 2034. Rather than relying on abrupt changes, the plan outlines growth from 83,700 in 2024 to 119,000 by 2034 and double the sector’s value from NZ$3.6 billion to NZ$7.2 billion. The plan takes a phased approach, tying growth to quality, sustainability and alignment with workforce needs.

Recent reforms include increasing in-study work limits from 20 to 25 hours per week, extending work rights to all tertiary exchange and study abroad students, and introducing a six-month post-study work visa for vocational graduates who do not qualify for longer-term rights. The government is also exploring easier access to multi-year visas. These measures aim to strengthen links between study, work experience, and skilled migration, while maintaining education quality and managing community impacts.

The path forward is about tackling root causes through careful, well-designed policy that extends beyond surface-level fixes

The strategy recognises the sector’s wider economic, social, cultural, and innovation-related value, and calls for closer coordination between education providers, employers, and industry. It also seeks market diversification beyond China and India, with targets to raise New Zealand’s profile globally and move more prospective students to rank it among their top three choices.

It’s interesting to see New Zealand’s sector leaders pairing an ambitious growth target with a deliberate, measured pace. Their emphasis on balancing enrolment growth with infrastructure, regional distribution and public support offers important lessons for other countries including Canada as we rethink our own approach to rebuilding and re-imagining international education in a way that is both sustainable and socially supported. While too early to measure outcomes, Going for Growth shows how long-term targets, coordinated reforms and predictable policy can build stability, avoiding the uncertainty that comes with abrupt changes.

British Columbia’s Approach

Closer to home, British Columbia has begun moving toward a more managed approach to international education one that offers useful reference points for other provinces to consider as they navigate similar pressures. The framework is designed to address key challenges: aligning enrolment with institutional and community capacity, encouraging more diversified student markets, connecting recruitment more closely to housing and student supports, and strengthening quality assurance to protect students and institutional reputation. More information on the province’s approach can be found in its Public Post-Secondary International Student Enrolment Guidelines, Education Quality Assurance framework, and requirements for multi-year institutional international education strategies.

This approach is still evolving, but it signals a shift away from reactive measures toward more deliberate, longer-term planning. The broader takeaway across all three cases – Germany’s coordinated national investment, New Zealand’s managed growth plan, and British Columbia’s emerging provincial framework – is not that any has found the perfect solution, but that more thoughtful, workable approaches are possible even within a federal system like Canada’s. The path forward is less about adding new barriers and complexity, and more about tackling root causes through careful, well-designed policy that extends beyond surface-level fixes.

A path forward for Canada

Canada requires a deliberate course correction, one that is precise in its objectives, strategic in its design and anchored in robust evidence. This entails moving beyond reactive decision-making toward a coherent framework that establishes clear long-term goals, calibrates enrolment to institutional and community capacity, and embeds international education as a core pillar of national economic, demographic and innovation strategies.

Achieving this demands sustained, structured coordination between federal, provincial and institutional partners, underpinned by transparency, reliable data and clearly defined performance metrics.

As Canada looks ahead, several key aspects should guide the development of a stronger, more sustainable international education strategy:

1. Transparency & accountability

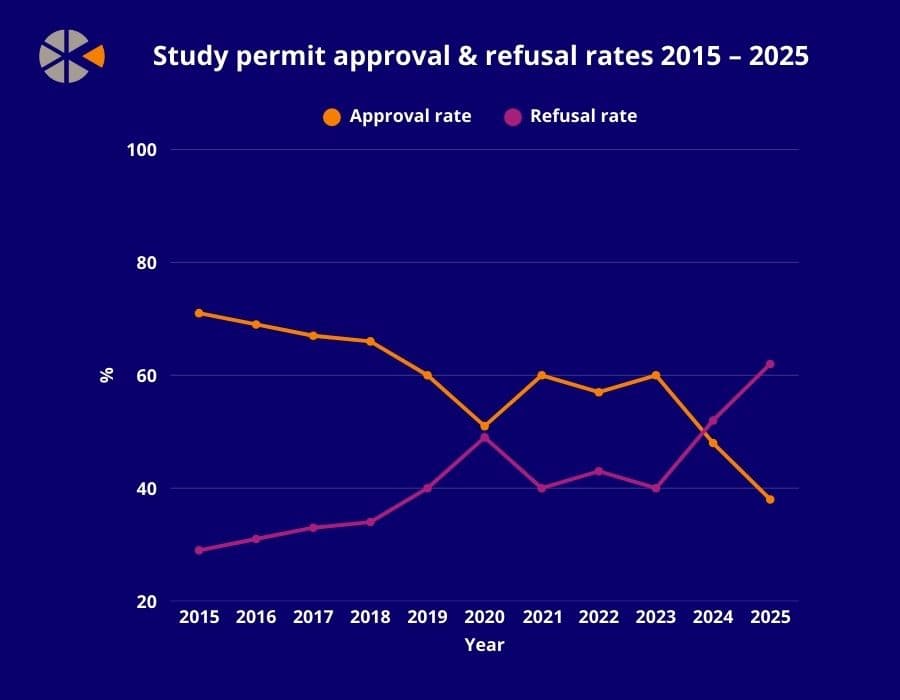

- Prioritise transparency by publishing timely, detailed data on study permit allocations, approval rates and processing times to enable evidence-based planning.

- Streamline compliance processes by redesigning the Provincial Attestation Letter process to remove unnecessary steps while maintaining accountability and integrity.

- Recognise sector diversity by applying policies that reflect institutional differences in size, mission, and track record, using a risk-based approach to oversight.

2. Integration & coordination

- Integrate policy planning across education, immigration and labour market needs so that international students are viewed as future members of Canada’s workforce and communities.

- Establish a national roundtable that brings together governments, institutions, employers and communities to coordinate talent, skills and immigration strategies (as recommended by many groups across Canada CBIE, UniCan, CICan).

3. Student success & retention

- Invest in student success by funding housing, mental health services, and academic supports that benefit both domestic and international learners, while creating clear residency pathways to encourage long-term retention.

- Adopt multi-year funding models for programs that link education with workforce integration, ensuring stability and continuity, similar to Germany’s FIT program.

4. Narrative & public confidence

- Reset the narrative by communicating the shared benefits of international education: sustaining academic programs, expanding opportunities, strengthening research capacity and contributing to Canada’s innovation ecosystem.

- Build public trust by showing that investments in international education are not a zero-sum trade-off with domestic priorities, but a shared investment in Canada’s prosperity, global competitiveness and community vitality.

Canada at a crossroads

Canada is at a crossroads. The past 20 months have exposed the cost of reactive, fragmented policy: instability for students, institutions and communities. The “building the plane while flying it” approach cannot continue. This is also a moment of opportunity. Canada can create a transparent, predictable and collaborative international education system, one that recognises students not as temporary visitors, but as future citizens if they choose to stay, or as global ambassadors for Canada: skilled professionals, community builders and partners in strengthening our place in the world.

Germany’s integration of higher education into its national skilled labour strategy and New Zealand’s long-term managed growth plan both demonstrate that it is possible to balance integrity, economic benefit and student success. British Columbia’s recent steps show that proactive, well-planned policy is possible within Canada’s governance structure, and that each province can develop its own approach tailored to its specific context, priorities and capacity

In a rapidly changing geopolitical environment, how Canada engages globally, attracts and retains talent, and integrates education with long-term national goals will shape its economic and social future. Canada can choose to lead with vision and strategy or watch as others secure the global talent, partnerships and influence that we have allowed to slip away.