Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of consulting for the Education Design Lab (EDL) on their search for a Learning Management System (LMS) that would accommodate Competency-Based Education (CBE). While many platforms, especially in the corporate Learning and Development space, talked about skill tracking and pathways in their marketing, the EDL team found a bewildering array of options that looked good in theory but failed in practice. My job was to help them separate the signal from the noise.

It turns out that only a few defining architectural features of an LMS will determine its fitness for CBE. These features are significant but not prohibitive development efforts. Rather, many of the firms we talked to, once they understood the true core requirements, said they could modify their platforms to accommodate CBE but do not currently see enough demand among customers to invest the resources required.

This white paper, which outlines the architectural principles I discovered during the engagement, is based on my consulting work with EDL and is released with their blessing. In addition to the white paper itself, I provide some suggestions for how to move the vendors and a few comments about other missing pieces in the CBE ecosystem that may be underappreciated.

The core principles

The four basic principles for an LMS or learning platform to support CBE are simple:

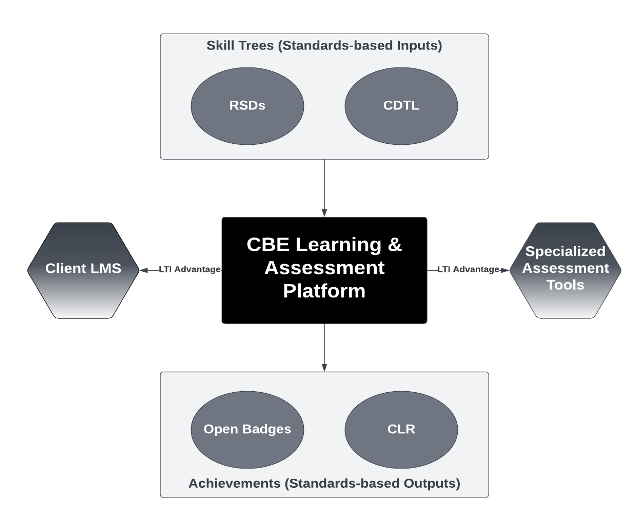

- Separate skill tree: Most systems have learning objectives that are attached to individual courses. The course is about the learning objectives. One of the goals of CBE is to create more granular tracking of progress that may run across courses. A skill learned in one course may count toward another. So a CBE platform must include a skill tree as a first-class citizen of the architecture, separate from the course.

- Mastery learning: This heading includes a range of features, from standardized and simplified grading (e.g., competent/non-yet) to gates in which learners may only pass to the next competency after mastering the one they’re on. Many learning platforms already have these features. But they are not tied to a separate skill tree in a coherent way that supports mastery learning. This is not a huge development effort if the skill tree exists. And in a true CBE platform, it could mean being able to get rid of the grade book, which is a hideous, painful, never-ending time sink for LMS product developers.

- Integration: In a traditional learning platform, the main integration points are with the registrar or talent management system (tracking registrations and final scores) and external tools that plug into the environment. A CBE platform must import skills, export evidence of achievement, and sometimes work as a delivery platform that gets wrapped into somebody else’s LMS (e.g., a university course built and run on their learning platform but appearing in a window of a corporate client’s learning platform). Most of these are not hard if the first two requirements are developed but they can require significant amounts of developer time.

- Evidence of achievement: CBE standards increasingly lean toward rich packages that provide not only certification of achievement but also evidence of it. That means the learner’s work must be exportable. This can get complicated, particularly if third-party tools are integrated to provide authentic assessments.

The full white paper is here:

(The download button is in the top right corner.)

Getting the vendors to move

Vendors are beginning to move toward support for CBE, albeit slowly and piecemeal. I emphasize that the problem is not a lack of capability on their part to support CBE. It’s a lack of perceived demand. Many platform vendors can support these changes if they understand the requirements and see strong demand for them. CBE-interested organizations can take steps to accelerate vendor progress.

First, provide the vendors with this white paper early in the selection process and tell them that your decision will be partly driven by their demonstrated ability to support the architecture described in the paper. Ask pointed questions and demand demos.

Second, go to interoperability standards bodies like 1EdTech and work with them to establish a CBE reference architecture. Nothing in the white paper requires new interoperability standards any more than it requires a radical, ground-up rebuild of a learning platform. But if a standards body were to put them together into one coherent picture and offer a certification suite to test for the integrations, it could help. (Testing for the platform-internal functionality like competency dashboards is often outside the remit of interoperability groups, although there’s no law preventing them from taking it on.)

Unfortunately, the mere existence of these standards and tests doesn’t guarantee that vendors will flock to implement CBE-friendly architectures. But the creation process can help rally a group that demonstrates demand while the existence of the standard itself makes the standard vendors have to meet clear and verifiable.

What’s still missing

Beyond the learning platform architecture, I see two pieces that seem to be under-discussed amid the impressive amount of CBE interoperability and coalition-building work that’s been happening lately. I already wrote about the first, which is capturing real job skills in real-time at a level of fidelity that will convince employers your competencies are meaningful to them. This is a hard problem, but it is becoming solvable with AI.

The second one is tricky to even characterize but it has to do with the content production pipeline. Curricular materials publishers, by and large, are not building their products in CBE-friendly ways. Between the weak third-party content pipeline and the chronic shortage of learning design talent relative to the need, CBE-focused institutions often either tie themselves in knots trying to solve this problem or throw up their hands, focusing on authentic certification and mentoring. But there’s a limit to how much you can improve retention and completion rates if you don’t have strong learning experiences, including formative assessments that enable you to track students’ progress toward competency, address the sticking points in learning particular skills, and so on. This is a tough bind since institutions can’t ignore the quality of learning materials, can’t rely on third parties, and can’t keep up with demand themselves.

Adding to this problem is a tendency to follow the CBE yellow brick road to what may look like its logical conclusion of atomizing everything. I’m talking about reusable learning objects. I first started experimenting with them at scale in 1998. By 2002, I had given up, writing instead about instructional design techniques to make recyclable learning objects. And that was within corporate training—as it is, not as we imagine it—which tends to focus on a handful of relatively low-level skills for limited and well-defined populations. The lack of a healthy Learning Object Repository (LOR) market should tell us something about how well reusable learning object strategy holds up under stress.

And yet, CBE enthusiasts continue to find it attractive. In theory, it fits well with the view of smaller learning chunks that show up in multiple contexts. In practice, the LOR usually does not solve the right problems in the right way. Version control, discoverability, learning chunk size, and reusability are all real problems that have to be addressed. But because real-world learning design needs often can’t be met with content legos, starting from a LOR and adding complexity to fix its shortcomings usually brings a lot of pain without commensurate gain.

There is a path through this architectural mess, just like there is a path through the learning platform mess. But it’s a complicated one that I won’t lay out in detail here.