On a grey March morning in 2008, a ministerial stand-in cut the ribbon on a £25 million glass and steel building that was supposed to transform Southend-on-Sea.

Then chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), David Eastwood had been hastily switched in as guest-of-honour to replace then-minister Bill Rammell.

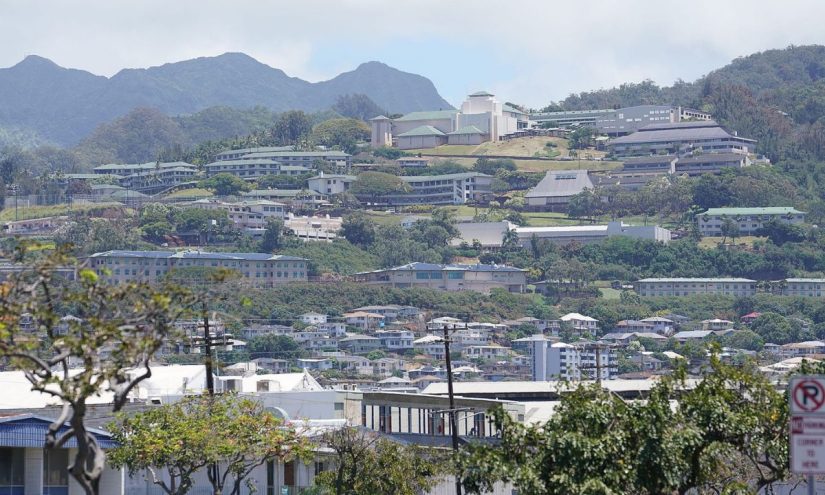

At the funding council, Eastwood had overseen the flow of millions in public money into this seaside town sixty miles east of London. Behind him was the University of Essex’s Gateway Building – six floors of lecture theatres, seminar rooms and local ambition.

The name had been suggested by Julian Abel, a local resident, chosen because it captured both the building’s location in the Thames Gateway regeneration zone and its promise as “a gateway to learning, business and ultimate success.”

Colin Riordan, the university’s vice chancellor, captured the spirit of the moment:

While new buildings are essential to this project, what we are about is changing people’s lives.

Local dignitaries toured the building’s three academic departments – the East 15 Acting School, the School of Entrepreneurship and Business, and the Department of Health and Human Sciences.

They admired the Business Incubation Centre designed to nurture local start-ups. They inspected the GP surgery and the state-of-the-art dental clinic where supervised students from Barts and The London would provide free treatment to locals – already 1,000 patients in just eight weeks.

![]()

This wasn’t just a university building. It was the physical manifestation of New Labour’s last great higher education experiment – the idea that you could transform left-behind places by planting universities in them – fixing “cold spots” and “left-behind places” with warm words and big buildings. It was as much economic infrastructure as it was education infrastructure.

Once, Southend had been “a magnet for day trippers”, then a shabby seaside resort, then a town so deprived that it attracted EU funding. Into that landscape dropped a £26.2 million glass box with “amazing views of the Thames Estuary on one side and a derelict Prudential block on the other,” explicitly aiming to revive the town’s flagging economy.

Riordan said the campus would “restore the physical fabric of the town centre” and act as a “magnet” for outsiders, while Eastwood supplied a line about a university being “global, national and local” at the same time – world-class research, national recruitment, local benefit.

Initially, Southend grew beyond the Gateway. East 15 got Clifftown Studios in a converted church, giving the town a theatre and performance space. The Forum – a joint public/university/college library and cultural hub – opened in 2013 as a flagship partnership between Southend Council, Essex and South Essex College, widely lauded as an innovative three-way civic project. For a while, Southend genuinely felt like a university town – at least in the city-centre streets around Elmer Approach.

![]()

But now seventeen years later, the University of Essex has announced it will close the Southend campus. The Gateway Building will be emptied, 400 jobs will go, and the town’s dream of becoming “a vibrant university town” may now end with recriminations about financial sustainability and falling international student numbers.

The council leader, Daniel Cowan, says:

…our city remains perfectly placed to play a major national role in higher education, business, and culture.”

But does it?

A gateway of excellence

To understand how Southend’s university dream died, we need to understand how it was born – in the marshlands of Thames Gateway, in the policy papers of Whitehall, and in the peculiar optimism of Britain in the mid-2000s, when anything seemed possible if you just built it.

In the dying days of the John Major years, to the east of London was a mess – dominated by derelict wharves, refineries and marshland – but it was also a potential route for the new Channel Tunnel Rail Link. In 1991, Michael Heseltine told MPs that the new line “could serve as an important catalyst for plans for the regeneration of that corridor” and announced a government-commissioned study into its potential.

![]()

The thinking was formalised in 1995, when ministers published the Thames Gateway Planning Framework (RPG9a) – regional planning guidance for a “major regional growth area” extending from Newham and Greenwich in London to Thurrock in Essex and Swale in Kent. It was very much late-Conservative spatial policy – trying to capture South East housing and employment growth in a defined corridor while using new infrastructure and land-use policy to civilise what one background paper called the “largest regeneration opportunity in Western Europe.”

New Labour scaled the whole thing up. In February 2003, John Prescott launched a Sustainable Communities Plan, which “set out a vision for housing and community development over the next 30 years”, with the Thames Gateway as its flagship growth area. Southend became the seaside town that would anchor the estuary’s eastern edge, absorb some of the new housing, and symbolise that this wasn’t just about London’s fringe – but about reviving places that had been left behind by deindustrialisation.

2001’s Thames Gateway South Essex vision even identified Southend’s future role as the cultural and intellectual hub and a “higher education centre of excellence for South Essex.”

In a 2006 Commons adjournment debate on “Southend (Regeneration)”, David Amess stitched the university and college expansions into promises of 13,000 new jobs and thousands of homes by 2021. Accommodating growth at the University of Essex Southend campus and South East Essex College, he argued, was key to turning the town centre into a “cultural hub”, alongside plans for a public and university library and performance and media centre.

![]()

By the time John Denham published A New University Challenge: Unlocking Britain’s Talent in March 2008, Southend was the exemplar. In the South Essex case study the prospectus tells a neat story – Essex’s involvement began in 2001 via validated programmes at South East Essex College, evolved into a “distinctive” partnership pulling a research-intensive university into a major widening participation and regeneration project.

With support from HEFCE, central and local government, it aimed to grow student numbers in the town from 700 to 2,000 by 2013 as “the beginning of a vision to make Southend a vibrant university town.”

Regeneration tales

There were plenty more. In “A New University Challenge,” Denham reminded readers that, since 2003, capital funding and additional student numbers had already gone into eleven areas – Barnsley, Cornwall, Cumbria, Darlington, Folkestone, Hastings, Medway, Oldham, Peterborough, Southend and Suffolk – with HEFCE agreeing support for six more – Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, Everton, Grimsby, and North and South Devon.

He estimated that around £100 million in capital had been committed so far, with capacity for some 9,000 students when all the projects were fully functioning.

![]()

Cornwall was another showcase. The Penryn (then Tremough) campus – developed through the Combined Universities in Cornwall scheme – used EU Objective One money and UK government funding via the South West RDA to build a shared site for Falmouth and Exeter in a county with historically low higher education participation and a fragile, seasonal economy.

Subsequent evidence to Parliament from Cornwall Council was explicit that CUC was designed to deliver economic regeneration as much as access, focusing European investment on “business-facing activity” and experimentation in outreach to firms that had never worked with universities before.

Cumbria got its own mini-origin story. Denham described the new University of Cumbria – launched in 2007 – as “a new kind of institution” with distributed campuses in urban and rural settings – designed to meet diverse learner needs and provide, with partners, the “skills that are essential” to create the workforce that would go on to decommission the Sellafield nuclear power plant.

Later DIUS reporting, REF environment statements and parliamentary evidence on the nuclear workforce all reprise the same themes – Cumbria as an anchor institution, a regional skills engine and a piece of the civil nuclear skills jigsaw.

Suffolk was presented as the archetypal “cold spot.” In 2005 UEA and Essex, backed by Suffolk County Council, Ipswich Borough Council, EEDA and the Learning and Skills Council, secured £15 million from HEFCE to create University Campus Suffolk on Ipswich Waterfront – a county of over half a million people with no university, low participation and significant planned growth.

Denham sold UCS as both a response to education under-supply and an enabler of economic regeneration. Later coverage in The Independent made the same point in more colourful language – Ipswich finally had its own glamorous waterfront campus “full of thousands of students.”

![]()

Barnsley, Oldham, Darlington and the like were framed more modestly – university centres in FE colleges that extended HE access to people “who might not otherwise consider participating in higher education.” In Barnsley’s case that meant a town-centre site opened in 2005 by Huddersfield, with investment from HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 funds, later taken over by Barnsley College but still offering Huddersfield-validated degrees and hosting around 1,600 HE students.

Folkestone, Hastings and Medway were presented as coastal or post-industrial variations on the theme – attempts to use university presence in under-served towns as a driver of creative-quarter regeneration, skills upgrading and image change. University Centre Folkestone, a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich joint venture, showed up in coastal regeneration reports as a way to tackle deprivation through improved skills and productivity in South Kent.

The Universities at Medway partnership between Kent, Greenwich, Canterbury Christ Church and Mid-Kent College was talked up in SEEDA case studies as a £50 million dockyard campus replacing thousands of lost shipbuilding jobs and housing over 10,000 students.

![]()

All of that was then plugged into the macro-economy story. Denham leaned on work suggesting that a one percentage point increase in the graduate share of the workforce raised productivity by around 0.5 per cent, and argued that higher education contributes over £50 billion a year to the UK economy, supporting 600,000 jobs.

The logic was pretty simple – if you want a more productive, knowledge-intensive economy, you need more graduates in more places – and not just in the big cities.

20 new universities

In March 2008 Denham called the scattered activity the “first wave” – and then announced a competition for the next one:

We believe we need a new ‘university challenge’ to bring the benefits of local higher education provision to bear across the country.

He got his headlines. He asked HEFCE to consult not just institutions but also RDAs, local authorities, business and community groups on how to identify locations and shape proposals. The goals were twofold – “unlocking the potential of towns and people” and “driving economic regeneration.”

HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund was given £150 million for the 2008–11 spending review. Denham suggested that over six years the fund could support up to twenty more centres or campuses, with commitments in place by 2014 and roughly 10,000 additional student places once mature.

The criteria for bids were revealing about the politics of the moment. Proposals had to demonstrate that they would widen participation, particularly among adults with level 3 who had never considered HE. They had to slot into local economic strategies – supplying high-level skills, supporting business start-ups and innovation, anchoring graduates who might otherwise leave. And they had to show strong HE/FE collaboration, buy-in from councils and RDAs, credible demand modelling, and the ability to manage complex multi-funded capital projects.

![]()

HEFCE dutifully ran a two-stage process – statements of intent followed by full business cases. By late 2009, after sifting twenty-three initial bids, the funding council concluded that six were strong enough to develop further, subject to the next spending review. Those six were Somerset (with Bournemouth University), Crawley (Brighton), Milton Keynes (Bedfordshire), Swindon (UWE), Thurrock (Essex) and the Wirral (Chester).

But the initiative wasn’t to last. The 2010 election brought a coalition government that scrapped RDAs, squeezed capital budgets and shifted the English HE settlement onto nine-thousand-ish fees and income-contingent loans. HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund withered. “Alternative providers” became the policy fashion – and the idea of a central pot funding twenty shiny new public campuses was in the past.

The promised headline – twenty new campuses, twenty new “university towns” – never happened. Instead we got a patchwork of university centres, joint ventures and re-badged FE HE hubs, while national rhetoric shifted from “unlocking towns and people” to “competition and choice.”

Four directions

If we look back now at the original seventeen, we find four basic trajectories.

Barnsley and Oldham have settled into the HE-in-FE pattern. University Campus Barnsley, opened in 2005 by Huddersfield with HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 support, transferred to Barnsley College in 2013 and now runs as the college’s HE arm, with Huddersfield still validating degrees. University Campus Oldham followed a similar route – opened in 2005 under Huddersfield’s banner and managed by Oldham College since 2012, delivering Huddersfield-validated awards alongside its own.

Cornwall and Medway look closer to what Denham imagined. The Penryn campus now hosts around 6,000 students on a shared Falmouth–Exeter site, with Objective One and SWRDA funding widely credited as crucial to its development.

Universities at Medway, established in 2004 at Chatham Maritime, has struggled – Canterbury Christ Church has all but pulled out, Kent’s numbers are small. The glossy case studies boasting of its £300 million boost to the local economy and its role in remaking a dockyard area that lost 7,000 jobs overnight look less glossy in 2025 – and now, of course, Kent and Greenwich are merging.

Cumbria and Suffolk were the two that ended up as fully fledged universities. The University of Cumbria, established in 2007 from a merger of colleges and satellite campuses, describes itself in REF and internal strategy documents as an “anchor institute” created to catalyse regional prosperity and pride, while continuing to play a role in the nuclear skills ecosystem around Sellafield. University Campus Suffolk secured university title and degree-awarding powers in 2016, with official narrative and sector commentary stressing its success in “transforming the provision of higher education in Suffolk and beyond” – although a significant proportion of its students are franchised.

Grimsby, Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, and the Devon centres fall into the “quietly important” category. The £20 million University Centre Grimsby opened in 2011 and now offers a large suite of higher-level programmes in partnership with Hull and through the TEC Partnership’s own degree-awarding powers. Grimsby Institute marketing describes it as a “dedicated home” for HE and one of England’s largest college-based providers. Similar stories play out in Blackburn, Blackpool and Petroc/South Devon – college-based university centres that rarely appear in the national HE debate but matter enormously for local progression and skills.

Folkestone and Hastings show us the fragility of hanging regeneration hopes on small coastal campuses. University Centre Folkestone operated from 2007 to 2013 as a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich initiative, featuring in coastal regeneration studies as a way to address deprivation and skills deficits and energise the creative quarter. But by the early 2010s it had wound down its HE offer, with the buildings folded into Folkestone’s broader cultural infrastructure.

Hastings saw an original centre replaced in 2009–10 by the University of Brighton in Hastings as the university’s fifth campus – itself the subject of fierce local protest when Brighton decided in 2016 to close the site and move provision into a partnership “university centre” model with Sussex Coast College.

![]()

Peterborough was a late-blooming outlier. The original University Centre Peterborough, developed with Anglia Ruskin, is now joined by ARU Peterborough – a campus opened in 2022 with significant “levelling up” funding and endlessly described by ministers as addressing a higher education cold spot and boosting local productivity. It was, in many ways, Denham’s model revived under a different party label – but few like it are left.

As for the “Universities Challenge” push, in Somerset, Bridgwater & Taunton College developed University Centre Somerset, offering degrees validated by HE partners. In Crawley, what had been imagined as a bid for a campus manifested as higher-level technical and university-level provision in Crawley College and the Sussex & Surrey Institute of Technology.

Milton Keynes’ ambitions funnelled into University Centre/Campus Milton Keynes, now part of the University of Bedfordshire, with periodic political chatter about eventually having a fully fledged MK university. On the Wirral, Wirral Met’s University Centre at Hamilton Campus offers degrees accredited by Chester, Liverpool and UCLan as part of a broader skills and regeneration role. Thurrock saw South Essex College expand its University Centre presence – exactly the sort of FE-based HE model Denham said he wanted.

Elsewhere, Chester has pulled out of Telford. Gloucestershire is winding down Cheltenham. The University College of Football Business (UCFB) no longer operates in Burnley. Man Met sold Crewe to Buckingham. USW is no longer in Newport, UWTSD is closing Lampeter, Durham is out of Stockton, and Cumbria has mothballed Ambleside.

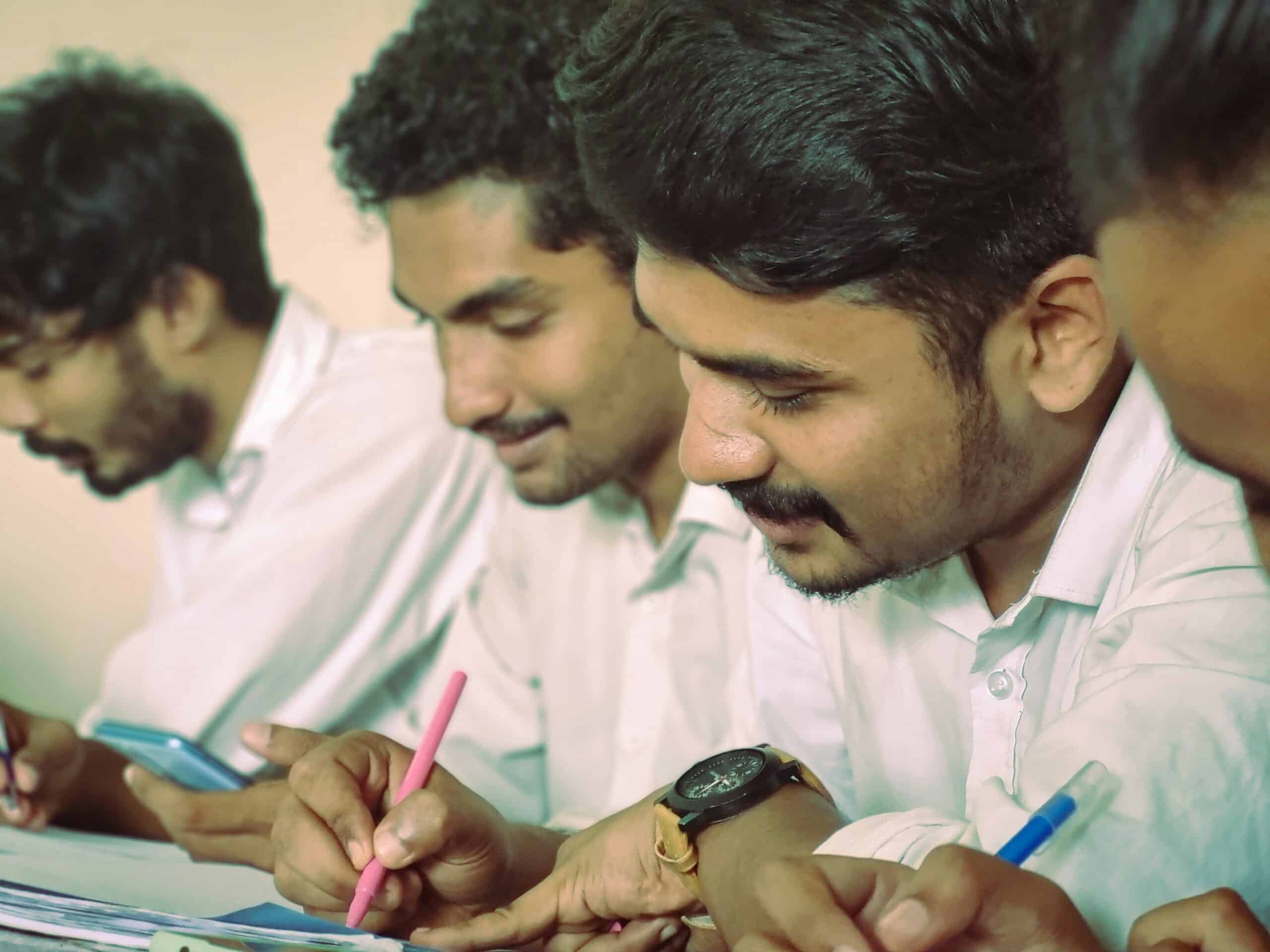

It turns out that on that grey March morning in 2008, David Eastwood was right. To sustain a full-fledged university campus – with all of the spill out benefits often envisaged – you need international students, national recruitment of home students and local students. Immigration policy change has made the first harder. A lack of deliberate student distribution has made the second harder. And closures like Southend’s leave local students like this.

I personally chose Southend due to being a single parent, wanting to build my career in nursing whilst getting that extra time with my little girl.

A new universities challenge

In its “National Conversation on Immigration” in 2018, citizens’ panels for British Future saw real benefits of international students – it called for student migration and university expansion to be used “to boost regional and local growth in under-performing areas,” and for any major expansion of student numbers to be government-led with the explicit aim of spreading the benefits more widely, including via regional quotas on post-study work visas and new institutions in cold spots.

It talked of “a new wave of university building” and said institutions should be located in places that have experienced economic decline, have fewer skilled local jobs, or are social mobility “cold spots” – with criteria including distance from existing universities and socio-economic need. They then give a worked list of ten suggested locations – Barnstaple, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Chesterfield, Derry-Londonderry, Doncaster, Grimsby, Shrewsbury, Southend and Wigan.

![]()

But as we’ve covered before, immigration policy – both during expansion and contraction – is almost always place-blind.

The Resolution Foundation’s Ending stagnation A New Economic Strategy for Britain makes a similar point – it rejects making existing campuses ever larger, and instead calls for new ones able to serve cold-spots “like Blackpool and Hartlepool.” It cites evidence that increasing the number of universities in a region – a 10 per cent rise – is associated with around a 0.4 per cent increase in GDP per capita.

This Tony Blair Institute paper from 2012 – surely the inspiration for Starmer’s 66 per cent target speech – calls for new universities in “left-behind regions” as a way to reduce spatial disparities and break intergenerational disadvantage. Chris Whitty’s 2021 report that highlighted the “overlooked” issues in coastal towns suggested shifting medical training to campuses in deprived towns.

And at a Policy Exchange event on the fringe of Conservative Party Conference that year, Michael “Minister for Levelling Up” Gove was asked about the potential for new universities to bring economic benefits to “places like Doncaster and Thanet.” Gove simply said: “I agree.”

The current Labour government’s Post-16 education and skills white paper makes familiar noises about addressing “cold spots in under-served regions.” But there’s no money for new campuses, no Strategic Development Fund, no New University Challenge. Instead, there’s a working group. And around the edges, we’re watching the geographical distribution of higher education shrink.

Without deliberate planning, sustained funding and political will, clustering will continue to cluster. Universities will consolidate in cities where mobile students want to study and where critical mass already exists. The cold spots will get colder.

OfS talks of universities needing “bold and transformative action.” It doesn’t mean transforming places – it means surviving financially. Even mergers save little money unless they lead to campus closures. And campus closures mean communities losing not just current educational provision but future possibility – the chance that their children might stay local and still get a degree, that their town might attract the businesses and cultural institutions that follow universities, that they might be something more than a void on the educational map.

The Robbins expansion of the 1960s worked because it created entire new institutions with sustained funding and genuine autonomy. The polytechnic expansion of the 1970s worked because it built on existing technical colleges with deep local roots. The conversion of polytechnics to universities in 1992 worked because it recognised existing success rather than trying to create it from nothing. But most attempts since to plant universities in cold spots through satellite campuses and partnership arrangements have struggled – because the system stubbornly refuses to pull levers based on place.

Promises of change

Once a university exits stage left, the impacts can be devastating. Despite promises that the merger and rebranding of the university into the University of South Wales in 2013 would not reduce campuses or student numbers, the 32-acre campus in Newport was closed in 2016 – when a largeish slice of arts and media courses moved to the Cardiff Atrium campus.

Student numbers in the city collapsed from around 10,000 in 2010/11 to just 2,600 a decade later – a drop that left the city, in the words of one local councillor, as “a poor man’s Pontypridd” when it comes to higher education.

The campus had been the city’s third highest employer – now the economic contribution of higher education to the local economy has all but evaporated. As one local put it:

There’s a lot of hate for students until they’re gone.

The Southend closure announcement came with promises too. The university would “support students through the transition.” The local council would “explore options for the site.” The MP would “fight for the community.”

Some will point the finger at the university. But we would be very foolish indeed to blame universities for shutting down campuses that they can’t sustain in a market-led model.

Doing so obscures the fundamental question – if universities are as crucial to regional development as everyone claims, why do we leave their geographical distribution to market forces? Why do we build campuses with regeneration money then expect them to survive on student fees? Why are we place-specific with our physical capital but place-blind with our human capital? Why do we keep repeating the same mistakes?

The answer is uncomfortable – because we’ve never really believed in geographical equity in higher education. We’ve played at it, thrown money at it during boom times, made speeches about it. But when times get hard, when choices must be made, the cold spots are always first to lose out.

The 1960s planners who chose Canterbury over Ashford and Colchester over Chelmsford understood that university location was too important to leave to chance. They made deliberate choices about where to invest for the long term. They understood that some places would need permanent subsidy to sustain provision, and they accepted that as the price of geographical equity.

We’ve lost that understanding. We’ve replaced planning with market mechanisms, strategy with initiatives, and long-term thinking with political cycles. Places like Southend are the ones that will pay the price – and sadly, it won’t be the last.

![]()