Rasha Faek, Managing Editor, WENR

Rebuilding Syria’s education system is not just about restoring classrooms, but about offering a chance for a lost generation to rebuild their lives and secure a better future for the country.

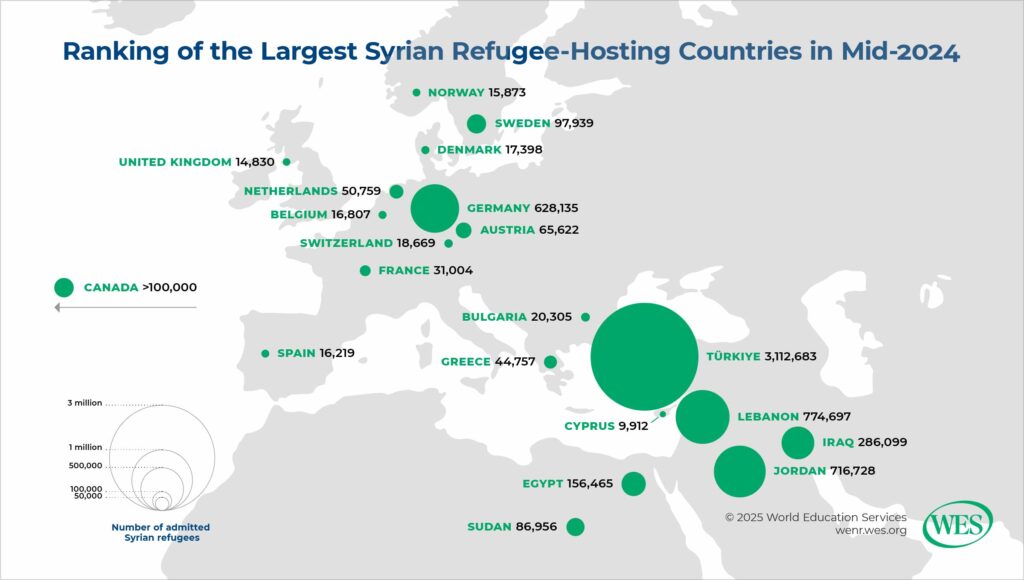

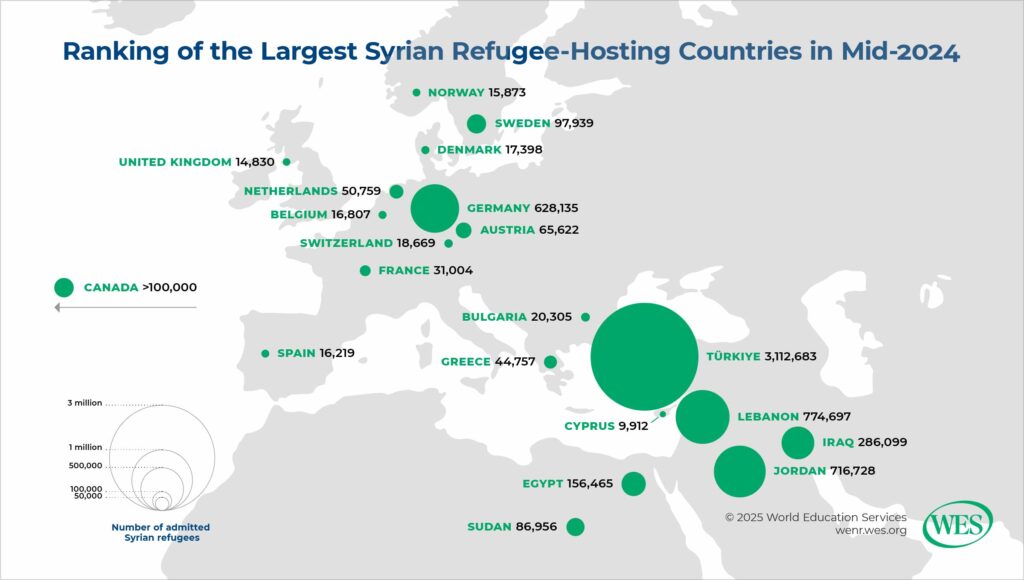

For over a decade, the Syrian conflict has cast a shadow over the future of an entire generation. The conflict began in 2011 as part of a wider wave of uprisings in the Arab world, with Syrians protesting the oppressive rule of President Bashar al-Assad. What started as peaceful demonstrations quickly escalated into a brutal war, pitting opposition groups, including extremist organizations like the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and foreign powers against the Assad regime and its supporters in Russia and Iran. The ensuing violence and destruction has resulted in one of the largest refugee displacements since World War II, with over 5.6 million Syrians seeking refuge in neighboring countries and beyond, and over 7.4 million displaced internally.

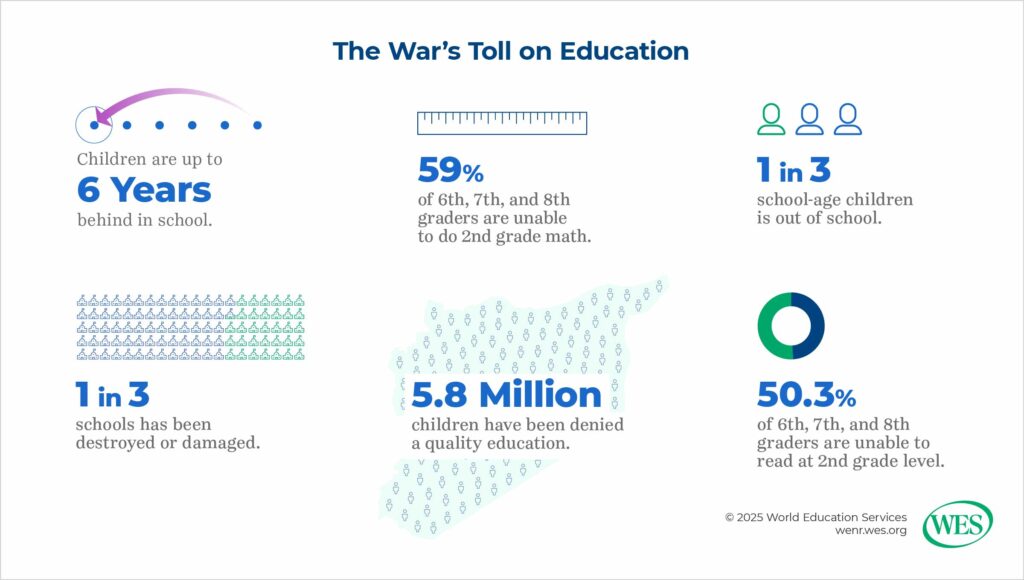

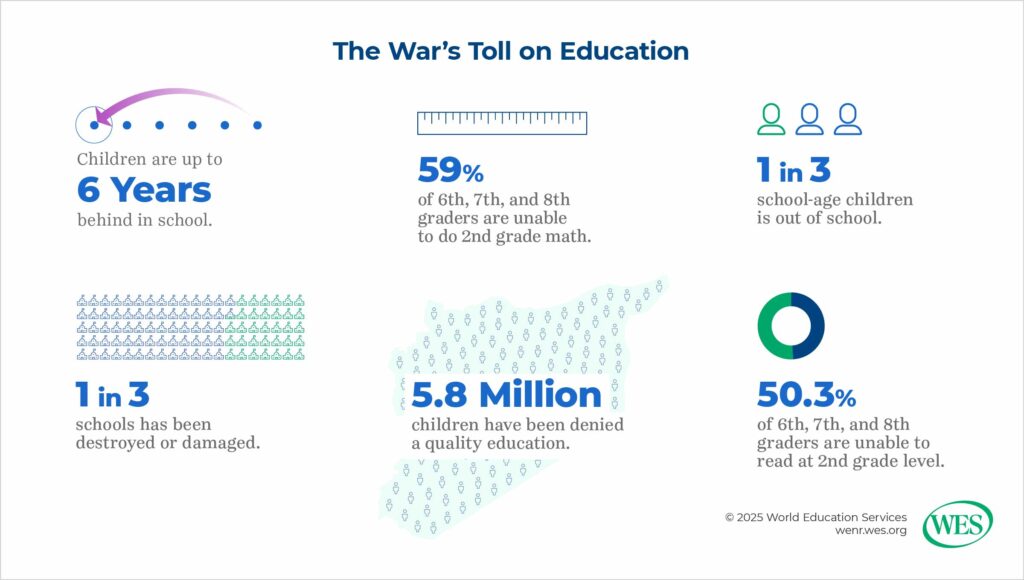

Syrian children—once filled with dreams of careers in medicine, science, and the arts—have had their education upended. The war destroyed or severely damaged nearly 50 percent of the country’s schools, leaving millions of children without access to education. Deprived of their right to learn, grow, and prepare for a better future, these children are at risk of becoming a “lost generation,” aid groups have worried.

Although finally over, the conflict has left the entire nation fractured and struggling to rebuild. Still, with the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, a unique opportunity now exists to rebuild not just Syria’s infrastructure and political systems, but the very foundation of its future: education.

“The deterioration of education in Syria stands as one of the most profound consequences of the prolonged 14-year conflict,” Radwan Ziadeh believes. A senior analyst at the Arab Center in Washington, D.C., Ziadeh is also founder of the Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies. “Addressing and prioritizing the restoration and reform of the education system is essential for the country’s recovery and long-term stability.”

However, this opportunity is fraught with challenges. Despite the tremendous potential for Syria now, there are critical concerns about the country’s future. The emergence of new power dynamics and competing interests could influence the direction of educational reforms. Amid these complexities, rebuilding an education system that meets the needs of displaced youth and others who have spent years in uncertainty will require careful planning and coordination among all stakeholders.

Syria’s Education System: A Snapshot Before the War

To rebuild successfully, Syria will need to learn from the strengths and weaknesses of its pre-war education system. Before the war, Syria’s education system was considered one of the most developed in the Arab world, marked by significant investment and broad access. In 2009, Syria allocated 5.1 percent of its GDP to education, considerably more than most other Arab countries even in 2022, reflecting the government’s focus on strengthening its educational infrastructure.

Elementary education, which spanned grades 1 to 6, was free and compulsory in pre-war Syria, and enrollment at that level reached nearly 100 percent by the time the conflict began. Secondary education, where pre-war enrollment reached 70 percent, was largely public and free, although students could pay fees to access certain programs based on academic performance. By 2014, over 2.5 million students were enrolled in elementary education, with nearly 3 million in secondary education. (To learn more, read “Education in Syria.”)

Higher education was also state funded, with seven public universities and 20 private. One of the most prominent institutions in the region, Damascus University, founded in 1923, attracted students from across the Arab world. By the 2012/13 academic year, about 659,000 students were enrolled in both public and private higher education institutions.

Despite its many successes, Syria’s education system faced a number of widely acknowledged challenges. For example, a defining feature of Syria’s pre-war education system was the use of Arabic as the language of instruction at all levels, not only elementary and secondary education but also higher education. All disciplines—including medicine, engineering, and the sciences—were taught in Arabic. While this policy was intended to promote the national language, it also faced criticism, particularly in higher education, as many Arab countries use English in scientific disciplines. Some critics argued that reliance on Arabic limited students’ access to global academic research and hindered their ability to participate in international academic and professional communities, where English or other languages were commonly used.

In Syria’s highly centralized higher education system, political interference, including political control over admissions and staff appointments, was also commonplace. “The education system was heavily influenced by the ideological preferences of the ruling regime, often resulting in an approach that focused more on indoctrination than critical thinking,” said Talal al-Shihabi, an engineering professor at Damascus University who obtained a doctoral degree from Northeastern University, in the United States.

The system also faced structural problems, such as overcrowded classrooms, outdated curricula, and limited research capacity. “The university admission policy, which aimed to accommodate a large number of students, contributed to a decline in the overall quality of education,” according to Al-Shihabi. “This challenge was further exacerbated by insufficient infrastructure and limited human resources, hindering the ability to provide quality education for all students.”

Finally, although public higher education was nominally free, the rise of private universities and paid pathways into public universities, such as parallel and open learning, led to greater numbers of students paying fees. By 2009, 44 percent of students were paying fees. This shift deepened social inequalities, as access to education became increasingly dependent on one’s financial resources, with only those who could afford to pay higher fees gaining enrollment.

“In reality, the success of education in Syria was largely driven by the individual efforts of Syrians to learn and develop skills, rather than by the education system itself,” al-Shihabi said.

Destruction of Educational Infrastructure Due to War

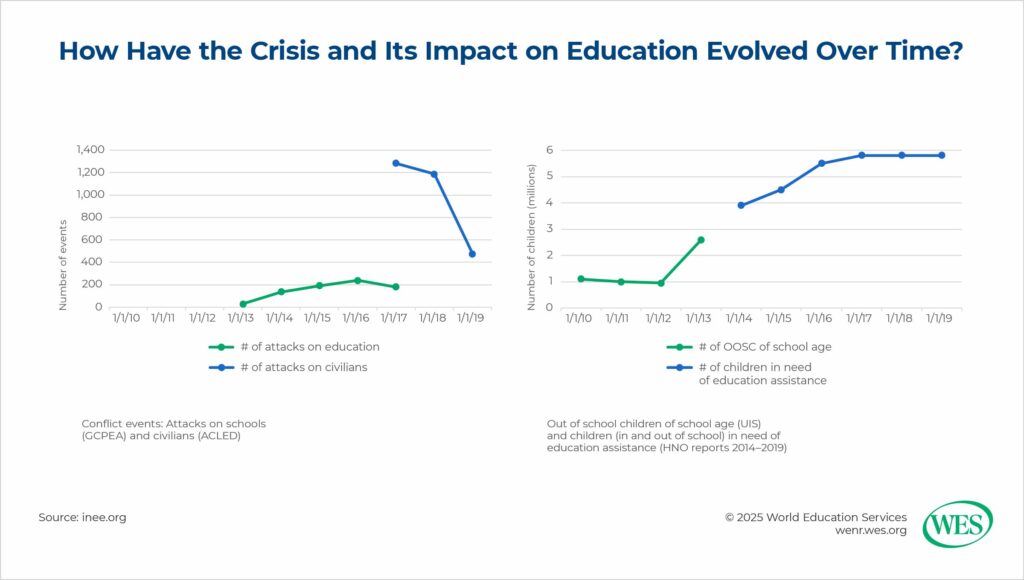

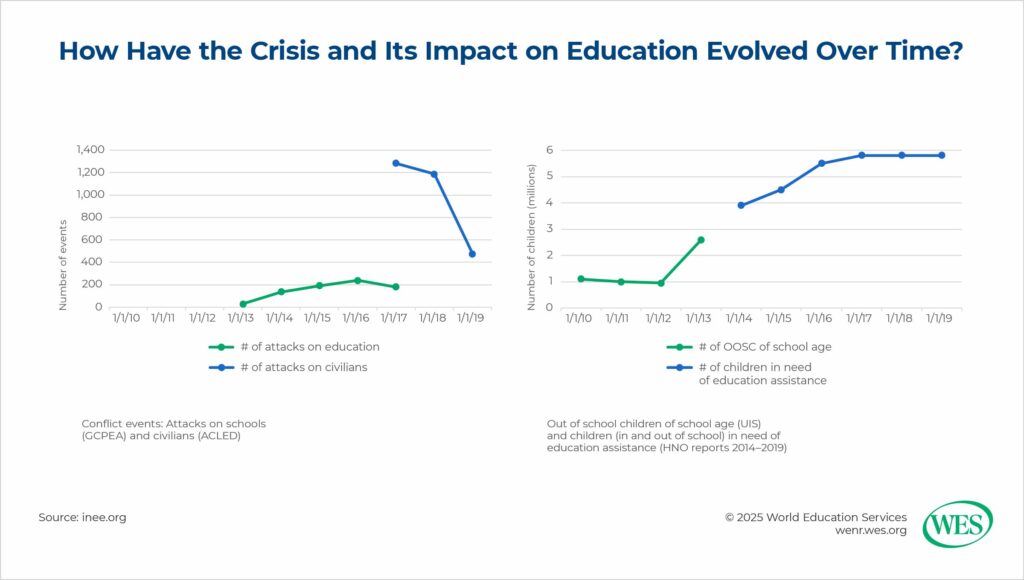

The conflict changed Syria’s education system profoundly. Across the country, fighting severely damaged infrastructure, including schools, universities, and educational facilities. Educational institutions were targeted, either directly by bombings or indirectly through the breakdown of local security and governance. UNICEF and other international bodies have reported that more than 7,000 schools have been damaged or destroyed by the fighting, with many located in the most affected areas: Aleppo, Idlib, and Daraa.

The war caused massive displacement of students and teachers, both within Syria and to neighboring countries. More than 7.4 million Syrians were internally displaced, while 5.6 million sought refuge abroad, according to the UNHCR. As a result, millions of children and young adults have been cut off from the opportunity to obtain an education.

Refugee children, especially in countries like Jordan, Lebanon, and Türkiye, faced overcrowded classrooms and a shortage of educational resources, exacerbating the difficulties involved in continuing their studies. In many cases, refugee children had to deal with language barriers, lack of qualified teachers, and shoddy facilities.

Continuing or accessing university education has proven even more difficult for Syrian refugees, especially for those lacking adequate documentation, such as birth certificates, identification, and academic records, which are often lost or unavailable. (Read two related articles: “The Importance of Higher Education for Syrian Refugees” and “The Refugee Crisis and Higher Education: Access Is One Issue. Credentials Are Another.”)

Furthermore, in some countries, like Lebanon and Türkiye, Arabic is not the medium of instruction. In these countries, students are required to demonstrate proficiency in the language of instruction before enrolling, creating yet another barrier to higher education.

Financing is also a common hurdle. Countries like Jordan and Lebanon treat refugees as if they are international students and charge them high tuition fees. Since 2015, a wave of scholarships from European organizations has offered some financial relief, but the funding has not been sufficient to meet the needs of all refugees. And as philanthropic support declined over the following years, the interest in university education among Syrian refugee students also waned. Many Syrian refugees in neighboring countries, where job opportunities after graduation were limited, began to question the value of a degree and to redirect their limited resources towards finding a way to migrate to Europe instead. Although educational opportunities for refugees in European countries, for those who reached one, were better, university education remained costly and unattainable for many.

“Education was merely focused on access at the expense of quality and continuity while being approached in a clustered manner rather than being holistic and integrated with protection, psychosocial support, and parents’ engagement,” said Massa Al-Mufti, founder and president of the Sonbola Group for Education and Development, which supports refugee education in Lebanon. “This limited view overlooked the fact that education in emergencies is not just about literacy and numeracy, it requires an understanding of the broader needs of the children, needs that encompass social, emotional, and family engagement,” she explained.

Children who remained in Syria throughout the war faced their own difficulties. The fragmentation of the country’s education system into regime-controlled and opposition-held areas further complicated matters, resulting in a disjointed sector with varying levels of access and quality.

In areas under opposition control, school closures were widespread. Teachers, facing threats from both government forces and armed opposition groups, struggled to teach. In some areas, opposition groups, including ISIS, imposed their own education policies, restricting or altering curricula to align with their ideology.

Still, new universities did emerge in non-regime-controlled areas, but they faced difficulties, including a lack of recognition, insufficient resources, and a shortage of qualified academic staff. This has further fractured the educational system in Syria, leaving large portions of the student population without access to an accredited education.

In areas controlled by the Assad regime, officials increasingly militarized the higher education sector, using it as a tool to control and suppress opposition movements. The regime intensified its control over universities, with security apparatuses, including Assad’s Ba’ath Party and the National Security Bureau, increasing their influence. Students and faculty members opposing the government were subjected to violence, purges, and imprisonment, while academic freedom was stifled.

The war also led to a rise in corruption within the education sector. Reports of forged certificates, bribery for grade manipulation, and favoritism in university admissions were common, especially with the government’s increasing reliance on loyalty to the regime as a condition for access to education and job opportunities. This deepened social inequalities, particularly for students who did not have the financial means or political connections to secure places at universities.

Despite the destruction and displacement, the number of students enrolling in higher education increased in government-controlled areas, partly because of relaxed entrance policies aimed at keeping students occupied and delaying their potential military conscription. In recent years, the number of enrolled students reached approximately 600,000, even though education quality had plummeted.

Brain drain, with many qualified academics fleeing the country, has further deteriorated the educational environment, leaving universities understaffed and underfunded. The ongoing political isolation of Syria, compounded by Western sanctions, has shifted the country’s academic relationships to other allies, such as Russia and Iran.

“The increase in the number of students coincided with a shortage of qualified teachers. A significant number of those sent abroad for doctoral studies before the war did not return, and the limited availability of scholarship opportunities, exacerbated by sanctions and the country’s isolation, has further reduced the pool of qualified new candidates,” said al-Shihabi. “As a result, some specialized fields, such as engineering and health disciplines, are left with very few teaching staff members over the last decade,” he noted.

“Over the past 14 years, continuing education inside Syria has been a constant struggle for both students and teachers. The ongoing lack of security, deteriorating living conditions, and the collapse of infrastructure have led to an unprecedented decline in the quality of education, resulting in a crisis of immeasurable proportions,” he said.

Rebuilding Syria’s Education Post-Assad

On December 8, 2024, opposition rebels advanced on Damascus and forced the collapse of the Assad regime. The Assad family fled to Russia. The rebels have since been in the process of attempting to take leadership of the country and form a new government.

The fall of the Assad regime presents Syria with a unique opportunity to rebuild after over a decade of conflict. Despite widespread destruction, schools and universities resumed operations shortly after the regime’s collapse, highlighting the resilience of Syria’s education sector. The government has also reinstated students expelled for political reasons, signaling a commitment to reconciliation.

Additionally, the new government has taken steps to remove any vestiges of the Assad rule. It has already begun revising the national curriculum, removing content tied to the former regime. Universities, such as Tishreen University in Latakia and Al-Baath University in Homs, have been renamed, to Latakia University and Homs University, respectively, to distance themselves from the Assad regime’s Ba’athist ideology. At the same time, the new government, composed largely of Islamist groups, has sparked controversy due to the increasing influence of Islamist themes in the new curriculum.

Significant work remains to fully capitalize on the opportunity to rebuild the country’s education system. A critical challenge in the rebuilding process is addressing the millions of children who missed years of schooling during the conflict. The return of refugees, many of whom have spent years in exile, further complicates this task. Many of these children are academically behind, having missed vital years of education. Specialized support will be necessary to help these returnees catch up academically, culturally, and psychosocially. Trauma-informed teaching and mental health support will be essential to ensure effective reintegration into classrooms. Language barriers also pose a significant challenge, as many returnee students are now fluent in languages such as English, French, or Turkish, making it difficult for them to adapt to the local curriculum in Arabic. Addressing these gaps through targeted language programs will be crucial for the returnees’ successful reintegration.

Al-Shahabi emphasizes the need for a comprehensive survey to assess both material damage in the education sector and human losses, highlighting the significant shortage of teaching staff due to emigration during the war, the suspension of foreign missions, and the return of those who went abroad.

Al-Shahabi also believes that meeting the immediate needs of Syria’s youth should be prioritized. This includes the development of alternative educational pathways, like vocational training and online learning platforms. Establishing training centers, funding e-learning initiatives, and offering sector-specific workshops will equip students with the practical skills necessary for Syria’s recovery, particularly in key sectors such as health care, construction, technology, and infrastructure repair.

Others echo his thoughts. “As we work toward Syria’s recovery, it is critical to focus on building practical skills for youth and offering them opportunities for real-world training,” Firas Deeb, executive director of Hermon Team, wrote in an email.

Deeb was a moderator at the IGNITE Syria: Rise & Rebuild conference held in Damascus on February 15. The conference highlighted other challenges, including regional disparities that complicate rebuilding efforts across the country. Urban centers like Damascus, Aleppo, and Latakia have more universities still standing, but the institutions still rely on outdated curricula. Access to private sector internships is limited, particularly in certain fields. Regions like Hasakah, Tartous, and Qamishli, which enjoy some economic stability, show potential in sectors like agriculture and renewable energy, but lack sufficient vocational training programs. In contrast, conflict-affected and rural areas such as Idlib, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, and Southern Syria face severely damaged educational infrastructure, a shortage of trained teachers and materials, and security risks that hinder students’ ability to pursue higher education.

“Many regions still lack vital resources such as electricity, clean water, and reliable internet, all of which are essential for effective education. Restoring these basic utilities must be prioritized to ensure that rebuilt schools can function effectively,” said Deeb. Still, he noted, “Rebuilding Syria’s educational infrastructure is crucial, but so too is reshaping curricula and teaching methods to create a modern, inclusive system.”

Others agree. “One of the most crucial areas for intervention is the professional development of teachers, which has been neglected in the past but is now a top priority,” said Al-Mufti. “Empowering teachers with advanced skills is vital for driving meaningful change in the education sector.”

Syria’s future depends on rebuilding an education system capable of preparing its youth to meet the challenges ahead. In the long term, the system must focus on developing its students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and practical skills—key elements necessary for the country’s reconstruction and for preparing a generation to lead Syria’s recovery. Universities will play a key role in training future professional engineers, doctors, scientists, and teachers who will help restore the country’s infrastructure and economy. Additionally, specialized fields such as medical care for war victims (including burn treatment and prosthetics), construction, urban planning, and technology will be essential in addressing the aftermath of the war.

“Rebuilding Syria’s education system goes beyond restoring institutions—it requires a fundamental redesign to align education with economic recovery,” Deeb said.

Collaborating for Syria’s Educational Recovery

The impact of rebuilding Syria’s education system could extend beyond the country’s borders. It could be a catalyst for stability and peace, offering hope not only for Syria’s future but also for the broader region and the world.

“Education should be prioritized alongside other urgent issues such as security and infrastructure, as it holds the potential to serve as a pathway to peacebuilding and reconciliation,” said Al-Mufti. “Education can play a transformative role in rebuilding Syria and providing its children with the skills needed for a peaceful future.”

This means that the international community also has a pivotal role to play in Syria’s recovery, particularly in rebuilding its educational infrastructure. “After years of isolation, it’s time for Syria to build partnerships with global universities and education systems to modernize curricula, emphasizing problem-solving and critical thinking. The support of the international community is essential to strengthening the education system,” Ziadeh said.

Lifting sanctions imposed on the former government will be vital to enabling investment to create a stable environment conducive to long-term educational reforms. This will open avenues for partnerships between Syrian and international universities, allowing for the development of programs tailored to the country’s educational needs, including curriculum reform and teacher training.

International organizations like UNESCO and the United Nations will play a pivotal role in providing technical expertise and resources to rebuild Syria’s education system. Collaboration with NGOs focused on education will also be essential in implementing localized programs for displaced populations and affected communities.

International cooperation will also be vital when addressing the needs of Syrians who were forced to flee during the war. While many advocate the return of refugees to Syria, it is important to recognize that the country is not yet fully stable. Many regions remain insecure, lacking essential services for a safe return. Refugees who have built lives in other countries also need continued local support, such as scholarships and other means of access to educational program. This will help ensure that Syria’s next generation is equipped to contribute to the country’s recovery. The focus should be on providing opportunities for refugees to acquire valuable skills abroad which they can bring back to Syria when conditions improve.

Ultimately, Syria’s education system will be central to the country’s long-term recovery. An educated, empowered youth will play a key role in rebuilding the nation’s infrastructure, revitalizing its economy, and ensuring its long-term stability. Investing in scholarships, vocational training, and international exchange programs will help rebuild Syria’s educational identity and equip the next generation to lead the country forward.

Rebuilding Syria’s education system is not just about restoring schools; it’s about empowering the next generation with the tools to rebuild a better, more united Syria. The support of the international community is essential to make this process inclusive, forward-thinking, and sustainable, ensuring that Syria heals and thrives once again.