Few people understand the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision to end race-conscious admissions in higher education better than Julie Park, a University of Maryland professor who has been studying race in college enrollment and admissions since long before it became a national flashpoint.

The case thrust her area of study into the limelight. She also served as a consulting expert on the side of Harvard University, one of two institutions—along with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—that Students for Fair Admissions sued over their race-conscious admissions policies.

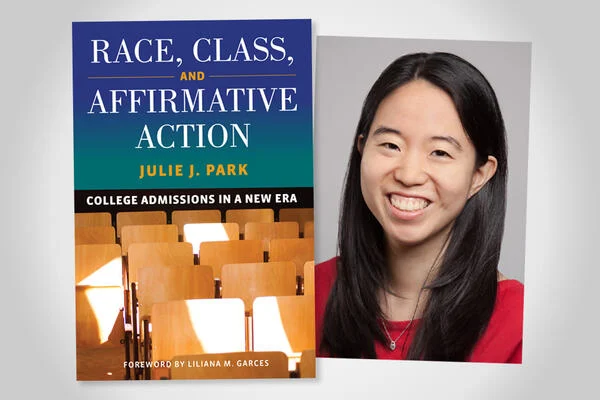

In her new book, Race, Class, and Affirmative Action (Harvard Education Press, 2026), Park explores how that seminal case has changed the admissions landscape, highlighting the ways the decision allows institutions to continue promoting racial diversity in their admissions processes. Written in early 2025, it also explores how President Trump has repeatedly wielded the SFFA decision as a tool to push forward anti-diversity, equity and inclusion policies.

The book aims to “document the current moment” in admissions, Park writes in the introduction. She spoke with Inside Higher Ed over the phone about where things stand coming up on three years after the SFFA decision.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: I appreciate that at the beginning of the book, you talk about your background, as well as how you got your start researching admissions. Could you talk a little bit about why you wanted to include some of those personal details in this book?

A: I think because the book is written purposefully in a conversational tone, and I bring some of my own story in here and there, or some of my observations, that it just made sense to talk about who I am, right? When you read a research article, you don’t always get that perspective. But I think, like it or not, we all have world views or life experiences that have shaped how we might think about something like college admissions. So, I wanted to be upfront with some of my own experiences and background for readers. And also, I think, given that Asian Americans have been such a central part of the Harvard case, I wanted to explain that I myself am Korean American, Asian American. I grew up in this type of immigrant community that talked a lot about colleges. But, then at the same time, I have other experiences that have shaped me, as well.

Q: From the very beginning of the book, you talk quite a bit about people’s perceptions of admissions and some of the myths that exist. Why do you think that college admissions are prone to mythologizing and misinformation?

A: I wrestled with it a lot in my last book [Race on Campus: Debunking Myths with Data [Harvard Education Press, 2018]. Like it or not, I think some of these entrenched perceptions are here to stay, but I keep trying to correct the record, and I think others do as well. I think sometimes it comes just from maybe misunderstanding, right? We know that we live in this TL,DR [too long, didn’t read] society. People aren’t always interested in the nuance. And so, something like race-conscious admissions, which is complex, even for people working in higher ed—they don’t always understand that the process is so nuanced, right? So, people will say things like, ‘oh, it’s involving quotas’ or ‘oh, students are only getting in because of race.’ And we know that’s not true from the research.

With young people, I think why they are vulnerable to some of these characterizations of race-conscious admissions is, when you’re applying to college, and if you’re 17 or 16, you kind of only know your own world. You know your own world the best. And so, sometimes within peer networks, the way people talk about college admissions can be really simplified. We hear people talk about, “oh, so-and-so got in, and they’re of this race, but so-and-so didn’t get in and they had higher SAT scores.” That becomes this urban legend, and that just kind of passes on, unfortunately, and reflects some of the popular discourse.

Q: You spend some time in the book talking about the flaws in admissions that already existed pre-SFFA. What are some ways that privilege and bias manifests in the admission system that people might not be aware of?

A: Oh, so many ways. People who are immersed in the admissions world might know this, but I think the general public is less aware of how things like college visits work, and who gets visited, who doesn’t get visited. I think the public have a sense of, “OK, private school kids are going to have a certain amount of privilege.” But it’s really layers upon layers; it’s not just one singular thing. If you connect the dots, and I talk about this somewhat in the book, you have this kind of pipeline where you have people who work in admissions offices, and then they go work at private schools. Like, do you think people just suddenly stop knowing each other? Of course not. Those are networks, for better or for worse.

And then, athletic recruitment. I wrestled with this once with a journal article reviewer, because they said, “Well, isn’t athletics more diverse?” But I thought it was really fascinating—I think this made it into the end notes, it didn’t go into the actual text. Because they were arguing, “Oh, athletics is dominated by these more diverse sports,” like basketball, football—which is true. Football does tend to have more racial, ethnic diversity. So, I actually took the time and I looked at the rosters of different big athletic schools, like University of Michigan, Alabama, etc. And then I looked at the athletic rosters at small liberal arts colleges, as well. And even I was surprised by the lack of diversity overall. Football is what takes up our minds, and football does take up a certain amount of sports, but there are so many other teams—swimming, golf, lacrosse, etc. They just add up. So, the cumulative total athletics ends up being pretty white.

Q: What are solutions for some of these things? Is there any way for colleges to separate out the people who are more on the “pay-to-play side,” versus people who have a passion and have succeeded in, say, an extracurricular despite their circumstances?

A: It’s really hard to say. Being a parent now, I’m very aware that everything is paid; even to be kind of mediocre is kind of expensive. My older kid, bless his heart, we are not doing piano to become a piano star. And I, too, took piano lessons, and I was terrible, right? And I took them until I was, I don’t know, 13. I was never very good, and it cost a lot of money. But it was sort of just this developmental thing, and I still am, in a weird way, glad I did it, because I can read music.

I just saw Alysa Liu, the figure skater—her dad said it cost about a million to have her career. So, to be really good, it costs so much money.

So how would colleges cut through that? I think it’s really difficult. In terms of more systemic reforms, thinking of the measure that certain liberal arts colleges did take to reduce the number of spots in the incoming class that were allocated basically to athletic recruitment—could they do it again? Could they reduce those numbers even more? This is [Division III]. These kids aren’t getting scholarships or anything like that. It’s like, what if you just filled those teams with the students who were able to get admitted, anyway. I understand that these institutions are just really wedded to the status quo in certain respects, which is why you still see legacy, right?

I do think [about] how to parse out the authentic student—I don’t know. And I raised this issue at the beginning and the end of the book: [There is] another big concern of what admissions has become in terms of performativity. It’s demanding on young people and just that stress and pressure to package yourself. I don’t think it’s healthy. I think it’d be a brave college to really reverse course.

Q: In this book, in the context of both admissions and the Trump administration’s broad reading of SFFA, that they’ve applied to non–admissions-related things, you really call on colleges to take a bold stand. But I obviously think a lot of colleges would say, we can’t be singled out right now. Can you talk more about what you think colleges should be doing in this moment?

A: After the decision in SFFA rolled out in 2023, college presidents were very public about condemning the decision, saying, “This is a terrible decision. We still value diversity. We value racial diversity.” They were very specific. How quickly things can change, right? I think it’s leadership, it’s the choice that people make. We just had this news [last week] that the Trump administration’s anti-DEI mandates, which were shut down in court—the Trump administration isn’t going to challenge that. But it’s just this roundabout—they got what they wanted, right? They got the compliance. They got preemptive, really preemptive compliance. And it’s really tricky. I mean, I’m not a college president, I’m not a general counsel, so I know I had the luxury of saying, “Stay true to yourself, everyone!” but I think these difficult times call for leadership.

Of course, I would like them to stand up for racial and ethnic diversity, and I think they should. Right now, institutions probably feel safer talking about economic diversity. If that’s the way to at least keep diversity in the conversation, then that might be part of things as well. The Trump administration has shown itself hostile even to certain efforts to advance economic diversity. That’s the area where we have a much larger legal bandwidth, to pursue economic diversity intentionally.

Q: The Trump administration has used the term “racial proxy” to describe some recruiting strategies, like geographic recruiting. What are your thoughts on how colleges should respond to that?

A: The stuff from the Trump administration, it’s important to read carefully. They’re saying, “[You can’t use] this as a proxy for race,” and then the colleges can just say, “We’re not using it as a proxy for race,” and they have a whole track record of saying, “We value geographic diversity; we value economic diversity.” And, honestly, economic diversity isn’t a great proxy for race. If they’re trying to use that as a proxy, they’re failing, because we are seeing these major regressions, especially in Black enrollment.

There’s a lot of bluster, and I know that sometimes institutions feel like they’re having to thread the needle or kind of maneuver things, but I don’t think they should back away from these efforts, because they’re greatly needed.

Q: On the other side of the coin, you talk about things that made you hopeful in research for this book. Can you tell me about some of those things?

A: It’s been such a demoralizing year. I think it is a hopeful book, or at least—I’m amazed that I closed it out and I said, “I did the deep dive into the research, and when I looked at what things actually said, I have hope.” Now, I recognize, in this current era, it’s just not about what’s legal or not legal; it’s about what this administration wants. Let’s hope—let’s collectively hope—that it won’t always be this way, and look at the options that still exist, both in the law and what institutions can do.

I talk about the Croson case, which is a little-known Supreme Court case from 1989. There is some legal precedent that says, “Hey, [institutions] actually could defend their efforts to expand access by saying that they have these programs either due to addressing specific past discrimination by that institution or entity, or through passive participation in some sort of industry that resulted in racial inequality.” Well, guess what? Everyone possibly participated in [such an] industry; the standardized testing industry, that’s a huge one, right?

I know it doesn’t feel politically feasible in the current era, but I think [continuing to use race in a limited way] is something that institutions should not dismiss. So that is something that gave me hope, just to see that that the door is not totally shut.

And I think reading the actual [SFFA] ruling, while it is not ideal, to recognize that it could have been worse. I think that the court tried to be as specific as possible in affirming that race still matters to individuals’ experiences, that institutions can still consider how students talk about race and the relevance of race to their lives and traits valued by institutions.