by Sharif El-Mekki and Heather Kirkpatrick, The Hechinger Report

November 25, 2025

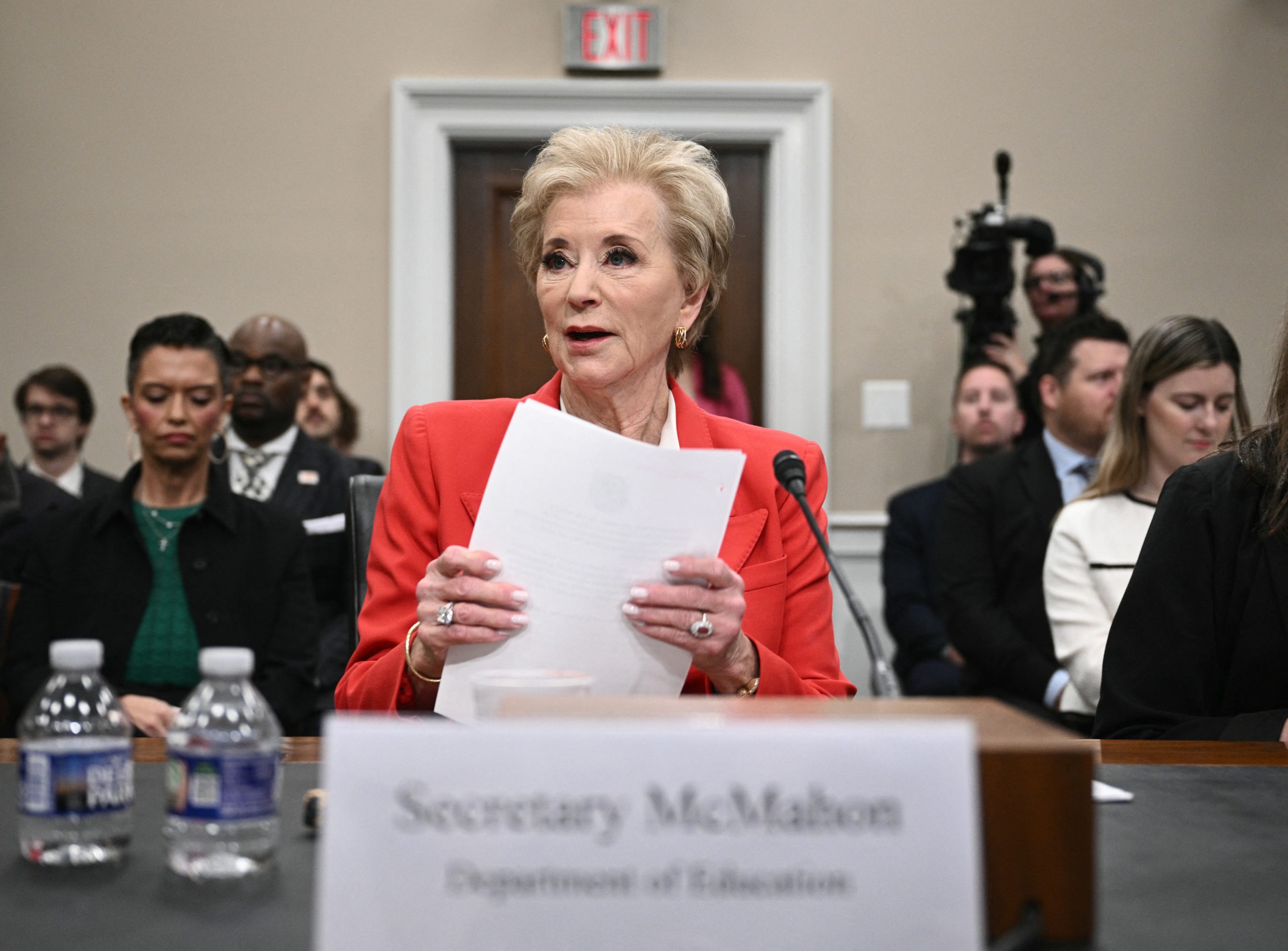

By dismantling the Department of Education, the Trump administration claims to be returning control of education to the states.

And while states and local school districts are doing their best to understand the new environments they are working in, they have an opportunity amidst the chaos to focus on what is most essential and prioritize how education dollars are spent.

That means recruiting and retaining more well-prepared teachers with their new budget autonomy. Myriad factors affect student learning, but research shows that the primary variable within a school’s control is the teacher. Other than parents, teachers are the adults who spend the most time with our children. Good teachers have been shown to singularly motivate students.

And that’s why, amidst the chaos of our current education politics, there is great opportunity.

Until recently, recruiting, preparing and retaining enough great teachers has not been a priority in policy or funding choices. That has been a mistake, because attracting additional teachers and preparing them to be truly excellent is arguably the single biggest lever policymakers can use to demonstrate their commitment to high-quality public schools.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

Great teachers, especially whole schools full of great teachers, do not just happen. We develop them through quality preparation and meaningful opportunities to practice the profession. When teachers are well-prepared, students thrive. Rigorous teacher preparation translates into stronger instruction, higher K-12 student achievement and a more resilient, equitable education system.

Teachers, like firefighters and police officers, are public servants. We rightly invest public dollars to train firefighters and police officers because their service is essential to the safety and well-being of our communities. Yet teachers — who shape our future through our kids — are too often asked to shoulder the costs of their own preparation.

Funding high-quality teacher preparation should be as nonnegotiable as funding other vital public service professions, especially because we face a teacher shortage — particularly in STEM fields, special education and rural and urban schools.

This is in no small part because many potential teaching candidates cannot afford the necessary education and credentialing.

Our current workforce systems were not built for today’s teaching candidates. They were not designed to support students who are financially vulnerable, part-time or first-generation, or those with caregiving responsibilities.

Yet the majority of tomorrow’s education workforce will likely come from these groups, all of whom have faced systemic barriers in accumulating the generational wealth needed to pursue degrees in higher education.

Some states have responded to this need by developing strong teacher development pathways. For example, California has committed hundreds of millions to growing the teacher pipeline through targeted residency programs and preparation initiatives, and its policies have enabled it to recruit and support more future teachers, including greater numbers of educators from historically underrepresented communities.

Pennsylvania has created more pathways into the education field with expedited credentialing and apprenticeships for high school students, and is investing millions of dollars in stipends for student teachers.

It has had success bringing more Black candidates into the teaching profession, which will likely improve student outcomes: Black boys from low-income families who have a Black teacher in third through fifth grades are 18 percent more interested in pursuing college and 29 percent less likely to drop out of high school, research shows. Pennsylvania also passed a senate billHYPERLINK “https://www.senatorhughes.com/big-win-in-harrisburg-creating-the-teacher-diversity-pipeline/” that paved the way for students who complete high school courses on education and teaching to be eligible for career and technical education credits.

At least half a dozen other states also provide various degrees of financial support for would-be teachers, including stipends, tuition assistance and fee waivers for credentialing.

One example is a one-year teacher residency program model, which recruits and prepares people in historically underserved communities to earn a mster’s degree and teaching credential.

Related: Federal policies risk worsening an already dire rural teacher shortage

Opening new pathways to teaching by providing financial support has two dramatic effects. First, when teachers stay in education, these earnings compound over time as alumni become mentor teachers and administrators, earning more each year.

Second, these new pathways can also improve student achievement, thanks to policies that support new teachers in rigorous teacher education programs.

For example, the Teaching Academy model, which operates in several states, including Pennsylvania, New York and Michigan, attracts, cultivates and supports high school students on the path to becoming educators, giving schools and districts an opportunity to build robust education programs that serve as strong foundations for meaningful and long-term careers in education, and providing aspiring educators a head start to becoming great teachers. Participants in the program are eligible for college scholarships, professional coaching and retention bonuses.

California, Pennsylvania and these other states have begun this work. We hope to encourage other state lawmakers to seize the opportunities arising from recent federal changes and use their power to invest in what matters most to student achievement —teachers and teacher preparation pathways.

Sharif El-Mekki is founder & CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development in Pennsylvania. Heather Kirkpatrick is president and CEO Alder Graduate School in California.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about teacher preparation programs was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-funding-high-quality-teacher-preparation-programs-should-be-the-highest-priority-for-policymakers/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=113500&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-funding-high-quality-teacher-preparation-programs-should-be-the-highest-priority-for-policymakers/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>