by Mehreen Ashraf, Eimear Nolan, Manual F Ramirez, Gazi Islam and Dirk Lindebaum

Walk into almost any university today, and you can be sure to encounter the topic of AI and how it affects higher education (HE). AI applications, especially large language models (LLM), have become part of everyday academic life, being used for drafting outlines, summarising readings, and even helping students to ‘think’. For some, the emergence of LLMs is a revolution that makes learning more efficient and accessible. For others, it signals something far more unsettling: a shift in how and by whom knowledge is controlled. This latter point is the focus of our new article published in Organization Studies.

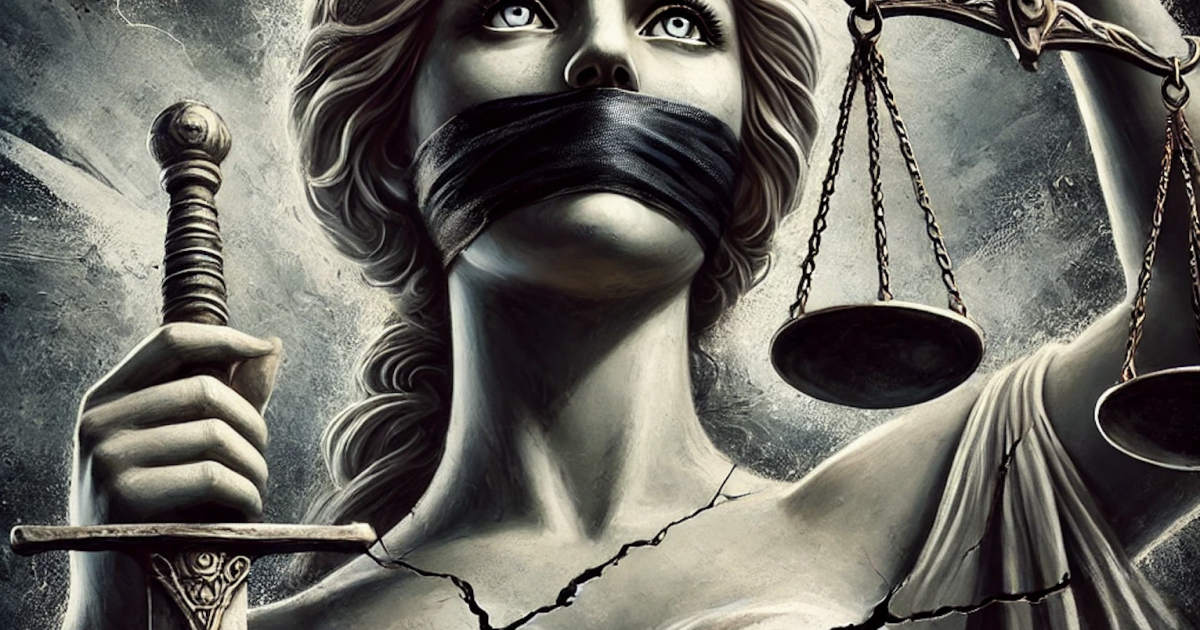

At the heart of our article is a shift in what is referred to epistemic (or knowledge) governance: the way in which knowledge is created, organised, and legitimised in HE. In plain terms, epistemic governance is about who gets to decide what counts as credible, whose voices are heard, and how the rules of knowing are set. Universities have historically been central to epistemic governance through peer review, academic freedom, teaching, and the public mission of scholarship. But as AI tools become deeply embedded in teaching and research, those rules are being rewritten not by educators or policymakers, but by the companies that own the technology.

From epistemic agents to epistemic consumers

Universities, academics, and students have traditionally been epistemic agents: active producers and interpreters of knowledge. They ask questions, test ideas, and challenge assumptions. But when we rely on AI systems to generate or validate content, we risk shifting from being agents of knowledge to consumers of knowledge. Technology takes on the heavy cognitive work: it finds sources, summarises arguments, and even produces prose that sounds academic. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of profound changes in the nature of intellectual work.

Students who rely on AI to tidy up their essays, or generate references, will learn less about the process of critically evaluating sources, connecting ideas and constructing arguments, which are essential for reasoning through complex problems. Academics who let AI draft research sections, or feed decision letters and reviewer reports into AI with the request that AI produces a ‘revision strategy’, might save time but lose the slow, reflective process that leads to original thought, while undercutting their own agency in the process. And institutions that embed AI into learning systems hand part of their epistemic governance – their authority to define what knowledge is and how it is judged – to private corporations.

This is not about individual laziness; it is structural. As Shoshana Zuboff argued in The age of surveillance capitalism, digital infrastructures do not just collect information, they reorganise how we value and act upon it. When universities become dependent on tools owned by big tech, they enter an ecosystem where the incentives are commercial, not educational.

Big tech and the politics of knowing

The idea that universities might lose control of knowledge sounds abstract, but it is already visible. Jisc’s 2024 framework on AI in tertiary education warns that institutions must not ‘outsource their intellectual labour to unaccountable systems,’ yet that outsourcing is happening quietly. Many UK universities, including the University of Oxford, have signed up to corporate AI platforms to be used by staff and students alike. This, in turn, facilitates the collection of data on learning behaviours that can be fed back into proprietary models.

This data loop gives big tech enormous influence over what is known and how it is known. A company’s algorithm can shape how research is accessed, which papers surface first, or which ‘learning outcomes’ appear most efficient to achieve. That’s epistemic governance in action: the invisible scaffolding that structures knowledge behind the scenes. At the same time, it is easy to see why AI technologies appeal to universities under pressure. AI tools promise speed, standardisation, lower costs, and measurable performance, all seductive in a sector struggling with staff shortages and audit culture. But those same features risk hollowing out the human side of scholarship: interpretation, dissent, and moral reasoning. The risk is not that AI will replace academics but that it will change them, turning universities from communities of inquiry into systems of verification.

The Humboldtian ideal and why it is still relevant

The modern research university was shaped by the 19th-century thinker Wilhelm von Humboldt, who imagined higher education as a public good, a space where teaching and research were united in the pursuit of understanding. The goal was not efficiency: it was freedom. Freedom to think, to question, to fail, and to imagine differently.

That ideal has never been perfectly achieved, but it remains a vital counterweight to market-driven logics that render AI a natural way forward in HE. When HE serves as a place of critical inquiry, it nourishes democracy itself. When it becomes a service industry optimised by algorithms, it risks producing what Žižek once called ‘humans who talk like chatbots’: fluent, but shallow.

The drift toward organised immaturity

Scholars like Andreas Scherer and colleagues describe this shift as organised immaturity: a condition where sociotechnical systems prompt us to stop thinking for ourselves. While AI tools appear to liberate us from labour, what is happening is that they are actually narrowing the space for judgment and doubt.

In HE, that immaturity shows up when students skip the reading because ‘ChatGPT can summarise it’, or when lecturers rely on AI slides rather than designing lessons for their own cohort. Each act seems harmless; but collectively, they erode our epistemic agency. The more we delegate cognition to systems optimised for efficiency, the less we cultivate the messy, reflective habits that sustain democratic thinking. Immanuel Kant once defined immaturity as ‘the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another.’ In the age of AI, that ‘other’ may well be an algorithm trained on millions of data points, but answerable to no one.

Reclaiming epistemic agency

So how can higher education reclaim its epistemic agency? The answer lies not only in rejecting AI but also in rethinking our possible relationships with it. Universities need to treat generative tools as objects of inquiry, not an invisible infrastructure. That means embedding critical digital literacy across curricula: not simply training students to use AI responsibly, but teaching them to question how it works, whose knowledge it privileges, and whose it leaves out.

In classrooms, educators could experiment with comparative exercises: have students write an essay on their own, then analyse an AI version of the same task. What’s missing? What assumptions are built in? How were students changed when the AI wrote the essay for them and when they wrote them themselves? As the Russell Group’s 2024 AI principles note, ‘critical engagement must remain at the heart of learning.’

In research, academics too must realise that their unique perspectives, disciplinary judgement, and interpretive voices matter, perhaps now more than ever, in a system where AI’s homogenisation of knowledge looms. We need to understand that the more we subscribe to values of optimisation and efficiency as preferred ways of doing academic work, the more natural the penetration of AI into HE will unfold.

Institutionally, universities might consider building open, transparent AI systems through consortia, rather than depending entirely on proprietary tools. This isn’t just about ethics; it’s about governance and ensuring that epistemic authority remains a public, democratic responsibility.

Why this matters to you

Epistemic governance and epistemic agency may sound like abstract academic terms, but they refer to something fundamental: the ability of societies and citizens (not just ‘workers’) to think for themselves when/if universities lose control over how knowledge is created, validated and shared. When that happens, we risk not just changing education but weakening democracy. As journalist George Monbiot recently wrote, ‘you cannot speak truth to power if power controls your words.’ The same is true for HE. We cannot speak truth to power if power now writes our essays, marks our assignments, and curates our reading lists.

Mehreen Ashraf is an Assistant Professor at Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, United Kingdom.

Eimear Nolan is an Associate Professor in International Business at Trinity Business School, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

Manuel F Ramirez is Lecturer in Organisation Studies at the University of Liverpool Management School, UK.

Gazi Islam is Professor of People, Organizations and Society at Grenoble Ecole de Management, France.

Dirk Lindebaum is Professor of Management and Organisation at the School of Management, University of Bath.