Under NATO, 32 countries have pledged to defend each other. Is the United States the glue that holds it all together?

Source link

Tag: Decoder

-

Decoder Replay: Isn’t all for one and one for all a good thing?

-

Decoder Replay: Can Taiwan fend off China forever?

But since 1949, Taiwan has functioned with de facto independence; it has its own government, military and currency. Yet the People’s Republic of China has always insisted that Taiwan is a part of the PRC.

China also insists that other countries respect its “One China” principle. Thus, only 12 countries recognise Taiwan as an independent country. They have diplomatic relations with Taiwan rather than the People’s Republic of China. These are mainly small nations in Latin America and the Pacific Islands.

Not surprisingly, the status of Taiwan has become a focal point for the great power rivalry between China and the United States.

Most Western countries, in contrast, have diplomatic relations with Beijing, and maintain representative offices in Taipei. The United States maintains unofficial relations with the people of Taiwan through the American Institute in Taiwan, a private nonprofit corporation, which performs U.S. citizen and consular services similar to those at embassies.

A diplomatic dance

Back in 1992, representatives of both Taiwan and China met and ironed out some conditions that could allow for relations across the Taiwan Strait. This became known as the 1992 Consensus. While it broadly committed both to the principle of “One China,” each interprets that differently; The People’s Republic sees Taiwan as a renegade state that must return at some point in the future, while Taiwan values its own autonomy.

Much to the chagrin of Beijing, the DPP does not accept the “1992 Consensus.”

Thus, there has been a dramatic deterioration in relations in recent years, especially since President Tsai’s presidency overlapped with that of the very assertive Chinese leader, Xi Jinping.

Many commentators now argue that the Taiwan Strait is the most dangerous region in the world.

China believes Taiwan must be unified with the mainland under the banner of its “One China” principle, and China’s claims to Taiwan are only intensifying in tandem with its growing economic power. The impatience of Xi Jinping was palpable in 2021 when he said that the “Taiwan issue cannot be passed on from generation to generation.”

Autonomy versus subjugation

Needless to say, Xi’s upping the ante has only exacerbated tensions across the Taiwan Strait — as have Beijing’s interference in the affairs of Hong Kong and the consequent deterioration in its freedom and human rights.

Hong Kong’s system of “one country, two systems” was once considered to be a possible model for Taiwan. But this is no longer the case.

Today, less than 10% of the Taiwanese people are in favor of unification with China. The majority prefer to keep the status quo. While feelings for independence are strong, the Taiwanese people are concerned that any move to independence would provoke Beijing — hence the widespread support for the status quo.

For its part, the United States has “acknowledged” (but not supported) the “One China” positions of both Beijing and Taipei. But the United States does not recognize Beijing’s sovereignty over Taiwan.

Nor does it recognise Taiwan as a sovereign country. According to official U.S. policy, Taiwan’s status is unsettled, and must be solved peacefully.

The United States stands by.

Back in 1979 when the United States recognised the People’s Republic of China and established diplomatic relations with it as the sole legitimate government of China, it also implemented the Taiwan Relations Act.

This requires the United States to have a policy “to provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character” and “to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

When Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT retreated to Taiwan in 1949, Taiwan was poorer than virtually all of the provinces of mainland China. But the Taiwanese economy would grow dramatically thanks to U.S. support, an increasingly well-educated and industrious workforce, a strong entrepreneurial spirit and the legacy of infrastructure and institutions from Japan’s colonisation of the island.

Today, Taiwan’s successful democratic capitalism is a strategic asset of the West. Its economy is a lynchpin in the global economy’s high-tech supply chains. In a world where democracy seems increasingly under threat, it is a beacon of democratic hope and inspiration. Taiwan also offers proof that democracy is not inconsistent with Chinese culture.

Taiwan’s position in the so-called “first island chain,” geographically located between U.S. allies Japan and the Philippines, is crucial to Washington’s foreign policy in the region at a time when China is trying to evict the United States from East Asia and behaving aggressively in the South China Sea.

China casts a big shadow.

The loss of Taiwan would undermine the credibility of the United States as an ally of Japan, Korea, the Philippines and Australia. If China took control of Taiwan, it could be freer to project power in the western Pacific and rival the United States.

While U.S. official policy toward Taiwan has remained unchanged over the years, the United States has been deepening its partnership with Taiwan in tandem with Xi Jinping’s assertive attitude over the past decade, thereby provoking Beijing’s anger. This has included increased arms sales and military training, and the visits of high-level U.S. Congress representatives, which Beijing interprets as conferring political recognition on Taiwan.

U.S. President Joe Biden has indicated four times that he would use the military to defend Taiwan if China ever attacked the island. The U.S. Congress has a strong resistance to the idea of sacrificing democratic Taiwan to the increasingly authoritarian Beijing.

And as recently as 20 April 2024 it passed a series of foreign aid bills that allocated $8 billion for Taiwan and other Indo-Pacific allies, along with much larger sums for Ukraine and Israel.

There is much speculation about the future of China-Taiwan relations by geopolitical analysts.

According to one school of thought, China faces a narrow window of opportunity, in light of its deteriorating economic prospects, to subjugate Taiwan. Thus many are alert to the possibility of China placing extreme pressure on Taiwan, including through a possible invasion over the coming years.

Others argue that Russia’s invasion and never-ending war with Ukraine make China hesitant to contemplate a similar operation in Taiwan. Taiwan’s mountainous geography and relatively shallow seas on the west coast would make an invasion much more challenging.

Is invasion a possibility?

The close location of U.S. forces in Japan and the Philippines mean that China would inevitably bump into the United States. And because China’s economy is so tightly integrated into Western-led supply chains, the cost of Western sanctions on China would be much greater than the sanctions on Russia.

The most likely scenario is that China will seek to subjugate Taiwan without overt military action, notably by cyber attacks, coercion, information warfare, harassment and threats. All things considered, with or without an invasion or direct military attacks, the Taiwan Straits will likely remain Asia’s biggest hot spot and occupy the attention of strategic planners for many years to come.

So are the Taiwan Straits the most dangerous region in the world?

Having recently spent 10 days visiting Taiwan with the Australian Institute of International Affairs, my answer is a resounding no. Taiwan and the Taiwanese people have a calm, relaxed and polite air. They seem immune to the bellicose, megaphone diplomacy of mainland China.

And as they continue to strengthen their economy and deepen their international friendships, their destiny would seem increasingly secure, although they need to invest much more in their military capabilities. But there will never be grounds for complacency — as the case of Hong Kong demonstrates, things can change virtually overnight.

Three questions to consider:

1. What autonomy does Taiwan currently have?

2. Why is Taiwan’s independence seen as important to other democratic nations in the region?

3. Do you think the United States should provide Taiwan military support to protect its autonomy?

-

Decoder Replay: Can we prepare for unpredictable weather?

There’s no denying climate change when a tornado rips through your town or a blizzard buries you in snow. So why blame the people who raise weather alarms?

Source link -

With News Decoder, students explore their role in the world

Back in 2020, during the height of the Covid epidemic, high school students in the U.S. state of Connecticut sat down with News Decoder founder Nelson Graves to explore a number of thorny topics that ranged from the death penalty to whether animals should be kept in zoos.

The students in “American Voices & Choices: Ethics in Modern Society” at Westover School had been working with News Decoder since the start of that academic year, mastering the process we call Pitch, Report, Draft and Revise — or PRDR — to identify topical issues at the intersection of ethics and public policy.

They pitched ideas they wanted to report on: teen health; police brutality; abortion; economic privilege in the environmental movement; the risks of experimental vaccines; the impact of alcohol on youth.

Later, each student received detailed feedback from a News Decoder editor, aimed at helping them narrow their research and produce original reporting.

Westover was an early News Decoder school partner. Since our founding 10 years ago, News Decoder has worked with high school and university students in 89 schools across 23 countries.

Decoding news in school

Teachers have used us as part of their course curricula, as extra credit assignments and as standalone learning opportunities for their students.

At Realgymnasium Rämibühl Zürich in Switzerland, teacher Martin Bott brings News Decoder in each year. In one weeklong workshop, students produced podcasts. Over five days, they pitched News Decoder stories about a problem they identified in their local communities, identified an expert to interview, found how that problem was relevant to people in other countries and then wrote a podcast script, revised it and recorded it. “[News Decoder] enabled me to do a few projects which really open up perspectives for the students, give them a taste of life beyond the classroom and of the world of journalism,” Bott said.

In another workshop for RGZH, News Decoder turned students into “foreign correspondents.” They were tasked with finding stories in Zurich that people in other countries would find interesting. Like the students in the podcasting workshop, they then found an expert to interview, wrote a draft and revised it with the goal of publishing it on News Decoder.

One student in the workshop noticed a demonstration of people with dogs and got up the nerve to talk to one of them. They were from an organization that rescued Spanish greyhounds and she decided it would be a good idea for a News Decoder story. The story she wrote ended up as one of News Decoder’s most-read stories of all time.

Not only have Bott’s students been able to publish stories on News Decoder, many of these stories, including the article about the greyhounds, have won awards in our twice yearly global storytelling competition.

“We’ve been delighted to get so many of those stories published on News Decoder,” Bott said. “That’s very, very motivating for the students. And it’s a wonderful learning process for them because they realise it’s not just about school rules and so on out there.”

Challenging students to do more

Bott said that working with professionals at News Decoder gets the students to step up. “When you’re a journalist, you’ve got a responsibility,” he said. “That’s something we’ve been able to talk about with journalists who’ve met us from various parts of the world through News Decoder. And you’ve got real pressure as well. And they’re not, I think they’re not quite used to that. So it really opens their eyes.”

At The Hewitt School in New York, 15 teens at the all-girls school meet once a month as a club. They read and discuss News Decoder stories and pitch their own stories. They also prepare for a cross-border webinar; each year they join with students from a News Decoder partner school in another country, and decide with those students on a topic to explore.

They then research the topic, interview experts and come together with the students from the other school to present their findings live in a video conference before an audience of people from the two schools.

In 2024, students from The Thacher School in California worked with peers at the European School of Brussels II on a webinar on consumerism and the human impacts of climate change.

Russell Spinney is faculty adviser for News Decoder at Thacher. “The webinars really were kind of ways just to get to know each other, discover that we actually do have some common interests. But not only that, that we also have problems that are similar,” he said.

“News Decoder’s workshops,” he said, “get students to think of ways to communicate their research beyond the classroom and connect with what’s going on in the world.” News Decoder has partnered schools this way in some 50 school-school webinars.

-

Can you believe it? | News Decoder

Can you tell the difference between a rumor and fact?

Let’s start with gossip. That’s where you talk or chat with people about other people. We do this all the time, right? Something becomes a rumor when you or someone else learn something specific through all the chit chat and then pass it on, through chats with other people or through social media.

A rumor can be about anyone and anything. The more nasty or naughty the tidbit, the greater the chance people will pass it on. When enough people spread it, it becomes viral. That’s where it seems to take on a life of its own.

A fact is something that can be proven or disproven. The thing is, both fact and rumor can be accepted as a sort of truth. In the classic song “The Boxer,” the American musician Paul Simon once sang, “a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

Once a piece of information has gone viral, whether fact or fiction, it is difficult to convince people who have accepted it that it isn’t true.

Fact and fiction

That’s why it is important — if you care about truth, that is — to determine whether or not a rumor is based on fact before you pass it on. That’s what ethical journalists do. Reporting is about finding evidence that can show whether something is true. Without evidence, journalists shouldn’t report something, or if they do they must make sure their readers or listeners understand that the information is based on speculation or unproven rumor.

There are two types of evidence they will look for: direct evidence and indirect evidence. The first is information you get first-hand — you experience or observe something yourself. All else is indirect. Rumor is third-hand: someone heard something from someone who heard it from the person who experienced it.

Most times you don’t know how many “hands” information has been through before it comes to you. Understand that in general, stories change every time they pass from one person to another.

If you don’t want to become a source of misinformation, then before you tell a story or pass on some piece of information, ask yourself these questions:

→ How do I know it?

→ Where did I get that information and do I know where that person or source got it?

→ Can I trace the information back to the original source?

→ What don’t I know about this?

Original and secondary sources

An original source might be yourself, if you were there when something happened. It might be a story told you by someone who was there when something happened — an eyewitness. It might be a report or study authored by someone or a group of people who gathered the data themselves.

Keep in mind though, that people see and experience things differently and two people who are eyewitness to the same event might have remarkably different memories of that event. How they tell a story often depends on their perspective and that often depends on how they relate to the people involved.

If you grow up with dogs, then when you see a big dog barking you might interpret that as the dog wants to play. But if you have been bitten by a dog, then a big dog barking seems threatening. Same dog, same circumstance, but contrasting perspectives based on your previous experience.

Pretty much everything else is second-hand: A report that gets its information from data collected elsewhere or from a study done by other researchers; a story told to you by someone who spoke to the person who experienced it.

But how do videos come into play? You see a video taken by someone else. That’s second-hand. But don’t you see what the person who took the video sees? Isn’t that almost the same as being an eyewitness?

Not really. Consider this. Someone tells you about an event. You say: “How do you know that happened?” They say: “I was there. I saw it.” That’s pretty convincing. Now, if they say: “I saw the video.” That’s isn’t as convincing. Why? Because you know that the video might not have shown all of what happened. It might have left out something significant. It might even have been edited or doctored in some way.

Is there evidence?

Alone, any one source of information might not be convincing, even eyewitness testimony. That’s why when ethical reporters are making accusations in a story or on a podcast, they provide multiple, different types of evidence — a story from an eyewitness, bolstered by an email sent to the person, along with a video, and data from a report.

It’s kind of like those scenes in murder mysteries where someone has to provide a solid alibi. They can say they were with their spouse, but do you believe the spouse?

If they were caught on CCTV, that’s pretty convincing. Oh, there’s that parking ticket they got when they were at the movies. And in their coat pocket is the receipt for the popcorn and soda they bought with a date and time on it.

Now, you don’t have to provide all that evidence every time you pass on a story you heard or read. If that were a requirement, conversations would turn really dull. We are all storytellers and we are geared to entertain. That means that when we tell a story we want to make it a good one. We exaggerate a little. We emphasize some parts and not others.

The goal here isn’t to take that fun away. But we do have a worldwide problem of misinformation and disinformation.

Do you want to be part of that problem or part of a solution? If the latter, all you have to do is this: Recognize what you actually know and separate it in your head from what you heard or saw second hand (from a video or photo or documentary) and let people know where you got that information so they can know.

Don’t pass on information as true when it might not be true or if it is only partially true. Don’t pretend to be more authoritative than you are.

And perhaps most important: What you don’t know might be as important as what you do know.

Questions to consider:

1. What is an example of an original source?

2. Why should you not totally trust information from a video?

3. Can you think of a a time when your memory of an event differed from that of someone else who was there?

-

Decoder Replay: Gold is valuable. But you can’t drink it.

We’re marking World Water Week, a gathering in Sweden intended to solve water-related challenges such as droughts, floods and food security. Let’s invest in it.

Source link -

Decoder Replay: Let’s celebrate Mandela Day

February 11, 1990 was truly a turning point in the history of South Africa.

For decades the nation at the southern tip of the continent had been pilloried by much of the rest of the world. This was because of its apartheid racial segregation laws that hugely favoured the white population over the far larger and mostly black majority.

Apartheid means “separateness” in Afrikaans, the language rooted in Dutch that evolved when the country was a colony.

By 1989 — itself a remarkable year for the wave of revolutions in communist East Europe — South Africa had made significant steps in its effort to end its pariah status. International sanctions were costing it dearly economically, culturally and in sporting terms.

As a taste of events to come, the government freed senior figures in the African National Congress (ANC), the exiled organisation waging a low-level guerrilla campaign against apartheid.

The fight against apartheid

A favourite weapon of the ANC was small mines. One of them exploded in a shopping mall in the commercial capital Johannesburg just as I had finished shopping there and was safely in the mall’s car park.

But there was no word when ANC leader Nelson Mandela — who ultimately spent 27 years incarcerated, much of it in an island prison — would be freed.

Lawyer Mandela entered the world stage with a famous speech at his 1963 trial for sabotage acts against the state in which he stated that freedom and equality were “an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Releasing Mandela from prison was a key card that South Africa could play to regain respectability, and the government would play it “soon,” Anton Lubowski, an anti-apartheid activist and human rights advocate, told me.

Lubowski did not live to see his forecast fulfilled. In September 1989, gunmen pumped AK-47 rifle rounds into him, with the coup de grace a pistol bullet. He was the latest in a long list of opposition figures in southern Africa to fall victim to unnamed assassins.

Freedom as news

Knowing that Mandela was expected to be released — his freedom would be a huge news story — but not knowing how or when it would happen was particularly frustrating for a news agency reporter like me.

Reuters and its rivals compete tooth and nail to get stories first, and to get them right. Being just one minute behind another news agency on a major story rates as a failure.

What I dreaded most was that Mandela would be released from prison unannounced, just as his ANC colleagues had been. This possibility made it necessary for me and my colleagues to be constantly alert, straining to catch the first authentic information.

The problem was that, then as now, the pressure to get hard information was compounded by a fog of fake news and hoaxes, saying that the release of Mandela was imminent or indeed had actually happened.

These claims were typically relayed on pagers, the messaging devices of the pre-smartphone age. Such messages, no matter how bogus-sounding, had to be checked. This took time and energy and shredded nerves.

Recognizing a hero

It was one such scare that prompted reporters to flock to an exclusive clinic outside Cape Town where Mandela was known to be undergoing treatment.

It was then that another problem surfaced: Nobody among us knew what Mandela looked like after his marathon spell in prison. There had been no pictures of him. Would we even recognise him if he walked out of the clinic?

The hilarious result was that every black man leaving the clinic — whether porter, delivery man, cleaner or whatever — came under intense scrutiny from the ranks of the world’s press assembled outside.

But on the timing of the release, I had a lucky break. A local journalist friend introduced me to a senior member of a secretive police unit who was willing to share with me whatever information he had on when Mandela would be a free man.

The police official’s name was Vic — I did not then know his full name. But he was no fake policeman. He introduced me to his staff in his offices, which were in a shopping arcade concealed behind what looked like a plain mirror but was in fact also a door.

Verifying fake claims.

All cloak-and-dagger stuff. With enormous lack of originality, my Reuters colleagues and I referred to Vic as our “Deep Throat,” the pseudonym of the informant who provided Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with information about the 1972 Watergate scandal.

Some time in the latter half of 1989, Vic told me in the less than cloak-and-dagger setting of a Holiday Inn coffee shop that Mandela was likely to be released in January or February of 1990.

This was not precise information, but at least it was better than anything that I had, or apparently anybody else in the news business.

In later meetings, Vic refined the information without disclosing the exact day of the release, which apparently was known to just four people in the South African government.

One of the ways Vic was valuable to us was that whenever a fake claim about Mandela’s whereabouts surfaced, I could call him, day or night, to check. And it was Vic who told me on February 10 that “it looked like” Mandela would be a free man the next day.

And so it proved.

Mandela instantly became universally recognisable, South Africa disbanded apartheid, elections were held in which all races voted, the ANC won, and Mandela became South Africa’s first fully democratically elected president.

February 11, 1990 is indeed a day to remember.

Three Questions to Consider

1. Why did apartheid last so long?

2. What was the reaction of South African whites to Mandela’s release?

3. Can you think of someone today who is trying to fight against an system of oppression?

-

Decoder Replay: Is truth self-evident?

Fake news is dangerous. But it’s hardly new.

More than 3,000 years ago, the largest chariot battle ever pitted the forces of one of the most powerful pharaohs of ancient Egypt — Ramesses the Great — against the Hittite Empire in Kadesh, near the modern-day border between Lebanon and Syria.

The battle ended in stalemate.

But once back in Egypt, Ramesses spread lies portraying the battle as a major victory for the Egyptians. He had scenes of himself killing his enemies put up on the walls of nearly all his temples.

It was propaganda. “It is all too clear that he was a stupid and culpably inefficient general and that he failed to gain his objectives at Kadesh,” Egyptologist John A. Wilson wrote.

Disinformation in ancient Rome

The Roman general Mark Antony killed himself with his sword after his defeat in the Battle of Actium upon hearing false rumors — fake news — propagated by his lover Cleopatra claiming that she had committed suicide.

American patriots, including the esteemed U.S. statesman and inventor Benjamin Franklin, and their British enemies swapped spurious allegations during the American Revolution that murderous Native Americans were working in league with their adversaries, scalping allies.

How about the 1938 radio drama, “The War of the Worlds”? Adopted from a novel by H.G. Wells, the radio broadcast fooled some listeners into believing that Martians had landed in America. Newspapers of the day said the broadcast sparked panic.

But historians today say the panic was exaggerated. So it was fake news about fake news!

There is no shortage of modern-day instances of fake news. In Myanmar in 2018, the military spearheaded a campaign of fake news, mainly on Facebook, claiming the Rohingya minority had murdered and raped members of the Buddhist majority. The Rohingya were described as dogs, maggots and rapists. The fake news helped trigger violence against the Rohingya that forced 700,000 people to flee their homes.

The irony is that many in Myanmar had turned to Facebook for information because the military had alienated many citizens with its control of the media. But the same military took advantage of the false reports to crack down on the Muslim minority.

Election falsehoods

Similarly, fake news has been used in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka to influence the outcome of elections, hide corruption and stir up religious animosity.

One of the ironies of fake news is it can embolden authoritarian governments to turn the tables and use made-up news as an excuse to crack down on the media. That can enable the regime to control the media message. In other words, fake news to the rescue of autocrats.

But we should not fool ourselves into thinking that fake news can be cured merely through technological solutions, that it’s a product of our times, that it’s mainly political and that it’s peddled only by our opponents. It’s not the property of any one political party or interest.

Fake news takes root in the gray area between truth and fiction, an area we can be quite comfortable in. There is something very enticing about fake news, especially if it aligns with our pre-conceived notions. Yet we are apt to think that fake news is the exception, a new aberration.

We can easily fall victim to fake news in part because we are not always disgusted by lies. We are taught at a very early age that deceit – deception, dishonesty, disinformation – is all around us. And that not all lies are as harmful as others. Our parents read us fairy tales from the earliest of ages, and many tales involve lies.

The telling of fairy tales

Take the ancient fable of “The Cock and the Fox,” included in the medieval collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, “One Thousand and One Nights.”

A hungry fox tries to coax a rooster out of a tree by telling him a tall tale — that there is universal friendship now among hunters and the hunted. The cock has nothing to fear, the wily fox says. It’s a lie, of course.

So, the equally wily cock resorts to his own lie: he tells the fox that he sees greyhounds running towards them, surely with a message from the King of Beasts. The fox, outwitted, runs away in fear. So here we have two lies in a single story. The moral? “The best liars are often caught in their own lies.”

Children and their parents are quite comfortable surrounded by lies. Is Santa Claus a malicious or harmless lie?

Do you know the story of the Wizard of Oz? That classic U.S. movie about a young girl lost in a fantasy world, pursued by witches, struggling to go home? The entire plot relies on a deceit – a supposedly powerful wizard who is nothing more than a bumbling, ordinary conman, who uses magic tricks to make himself seem great and powerful.

Deceit at the service of entertainment.

Advertisements are often innocent exaggerations, fiction if you will in the service of business and profit-making. But sometimes ads can veer into falsehoods.

So fake news is not new. And we’re no strangers to lies. What does that mean for those of us interested in making the world a better place? Should we simply give up because the task is too great?

Hardly. The lesson is that truth is not black and white, but grey, and it’s a moving target.

Take, for example, colonialism. From the 15th century on, white Europeans conquered huge swathes of the Americas, Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Oceania. They subjugated millions of people, using brutal violence in many places to subdue indigenous populations. They brought diseases that wiped out millions.

They exploited natural resources, using native labor and pocketing most of the profit from sales into a global trading network that they established. By 1914, Europeans had gained control of 84% of the globe.

We know all of that now because colonized peoples have revolted against their colonial rulers and won independence. The wars of independence have been won, yet so many countries around the world are still grappling with the shameful effects of colonialism and racism.

The ambiguity of truth

But would everyone have agreed on that depiction of Europeans as rapacious colonialists before the wars of independence?

Certainly not most of the Europeans, who believed they were exporting a superior civilization to backward natives. Missionaries who led many colonial ventures believed they were doing God’s will by converting native populations to Christianity. And not a few natives turned a blind eye to atrocities and benefited financially.

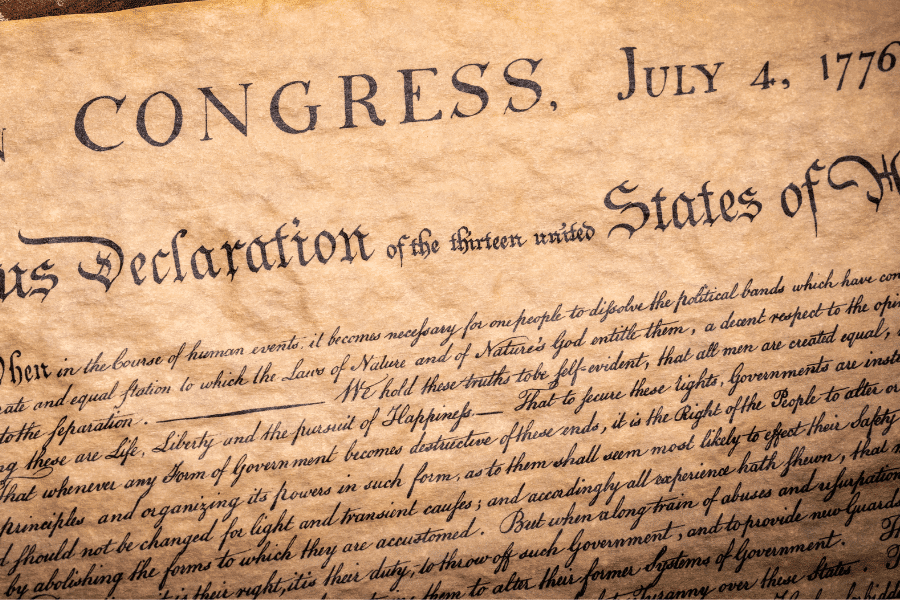

For a glaring example of the ambiguity of truth, take the United States. Its Declaration of Independence, borrowing from the French enlightenment, states that “all men are created equal,” with “unalienable Rights” to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” It put notions of freedom and equality at the heart of the American experiment. Yet it was written by a slave owner, Thomas Jefferson, and represented 13 colonies that all, to one degree or another, allowed slavery.

Convinced of their superiority and driven by an almost unquenchable appetite for wealth, white settlers drove Native Indians from their homes. The U.S. government authorized more than 1,500 attacks and raids on Indians. By the end of the 19th century, fewer than 238,000 indigenous people remained, down from some 5-15 million living in North America when Columbus arrived in 1492.

What is more, settlers in the South imported slaves from Africa, forcing them to work on vast plantations and denying them the very rights to life and liberty spelled out in the Declaration of Independence.

Rights and repercussions

Both Native Indians and African Americans are struggling to this day to come to terms with the treatment they suffered at the hands of the white colonials.

Would a white settler have seen himself or herself as a murderer? Hardly. In their minds, they were doing God’s work.

Mind you, the desire to colonize is not peculiar to Europeans. Imperial Japan and imperialist China both established overseas empires. The Empire of Japan seized most of China and Manchuria. To this day, Chinese nationals and South Koreans harbor ill feelings towards the Japanese. Chinese dynasties won control over parts of Vietnam and Korea.

There’s an expression in newsrooms around the world: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” Put another way, the same individual might seem a terrorist to some, a hero to others.

Take Yagan, a 19th century indigenous Australian warrior from the Noongar people. He played a key role in early resistance to British colonial rule in an area that is now Perth. His execution by a young settler figures in Australian history as a symbol of the unjust treatment of indigenous peoples by colonial settlers.

A hero to his people, he was a murderer in the eyes of the British.

Different perspectives on history

Or take the Incan emperor, Atahualpa, who resisted the explorer and conquistador Francisco Pizarro, to this day a Spanish hero. Pizarro forced Atahualpa to convert to Christianity before eventually killing him, hastening the end of one of the greatest imperial states in human history.

How you view Pizarro may depend on where you are sitting and when you lived.

There are countless modern examples of radically different perspectives on events. Such discrepancies may be inevitable. Dogged journalists can shed light on events and protagonists, and help shape history – for better or for worse.

Joseph McCarthy was a U.S. senator who in the early years of the Cold War spearheaded a smear campaign against alleged Communist and Soviet spies. Only courageous reporting by a small group of journalists who dared question McCarthy’s tactics and risked being tarred as Communist sympathizers themselves led to McCarthy’s downfall.

Joseph McCarthy (L) with his attorney Roy Cohn, who later mentored Donald Trump (Wikimedia Commons)

The New York Times and Washington Post went out on a legal limb when in 1971 they published the Pentagon Papers, a U.S. government history of the Vietnam War that laid bare official lies that drove American policy for more than a decade in Southeast Asia.

The government called the man who leaked the government documents a criminal and sought to prevent the newspapers from publishing the damning revelations.

The newspapers won their case before the Supreme Court, and their reporting increased public pressure on the government to withdraw from Vietnam.

Watergate upended a presidency.

You’ve perhaps heard of Watergate? Literally speaking, it’s a hotel in Washington, DC. But it has come to stand for the dogged and courageous news reporting by two journalists with the Washington Post who exposed crimes by President Richard Nixon and helped lead to his resignation in 1974.

Courageous investigative journalism is hardly confined to the United States. A non-profit news outfit called AmaBhungane — in Zulu, “dung beetle,” an animal that digs through shit – has reported on corrupt business deals at the highest levels of South Africa’s government.

In the Arab world, investigative journalists in Egypt, Yemen, Tunisia, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Bahrain, Palestine, Mauritania, Algeria, Kuwait and Sudan have uncovered tax evasion, money laundering, drug smuggling, torture and slavery. They have unmasked doctors who have removed the wombs of mentally disabled girls with the consent of parents.

But it’s not all easy sailing. According to Freedom House, in 2017 there were only 175 investigative journalists in all of China, down 58% since 2011.

What does this mean for you, a young activist who wants to help change the world?

Truth is murky.

The lesson is that the truth may not lie squarely on one side or the other, but rather in a murky, grey area. It can take courage to shine a light in the shadows, teeming with lies. And you may have to hear viewpoints that differ radically from your own. It pays to listen.

Progress against racism, inequality and injustice depends on an informed public.

The best journalists recognize their responsibility to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which state that: all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights; and everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

As the third U.S. President Thomas Jefferson said: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

So stick up for your rights, including the right to free expression. Be fair. And remember that one man’s terrorist may be another man’s freedom fighter. You don’t have a lock on the truth.

Questions to consider:

1. Why is it important to understand that fake news is nothing new?

2. Do you think there is any way to stamp out fake news?

3. What does it mean to say, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”?

-

Decoder Replay: Australia waltzes with two superpowers

The index ranks 26 countries and territories in terms of their capacity to shape their external environment. It evaluates international power through 133 indicators across themes including military capability and defense networks, economic capability, diplomatic and cultural influence, as well as resilience and future resources.

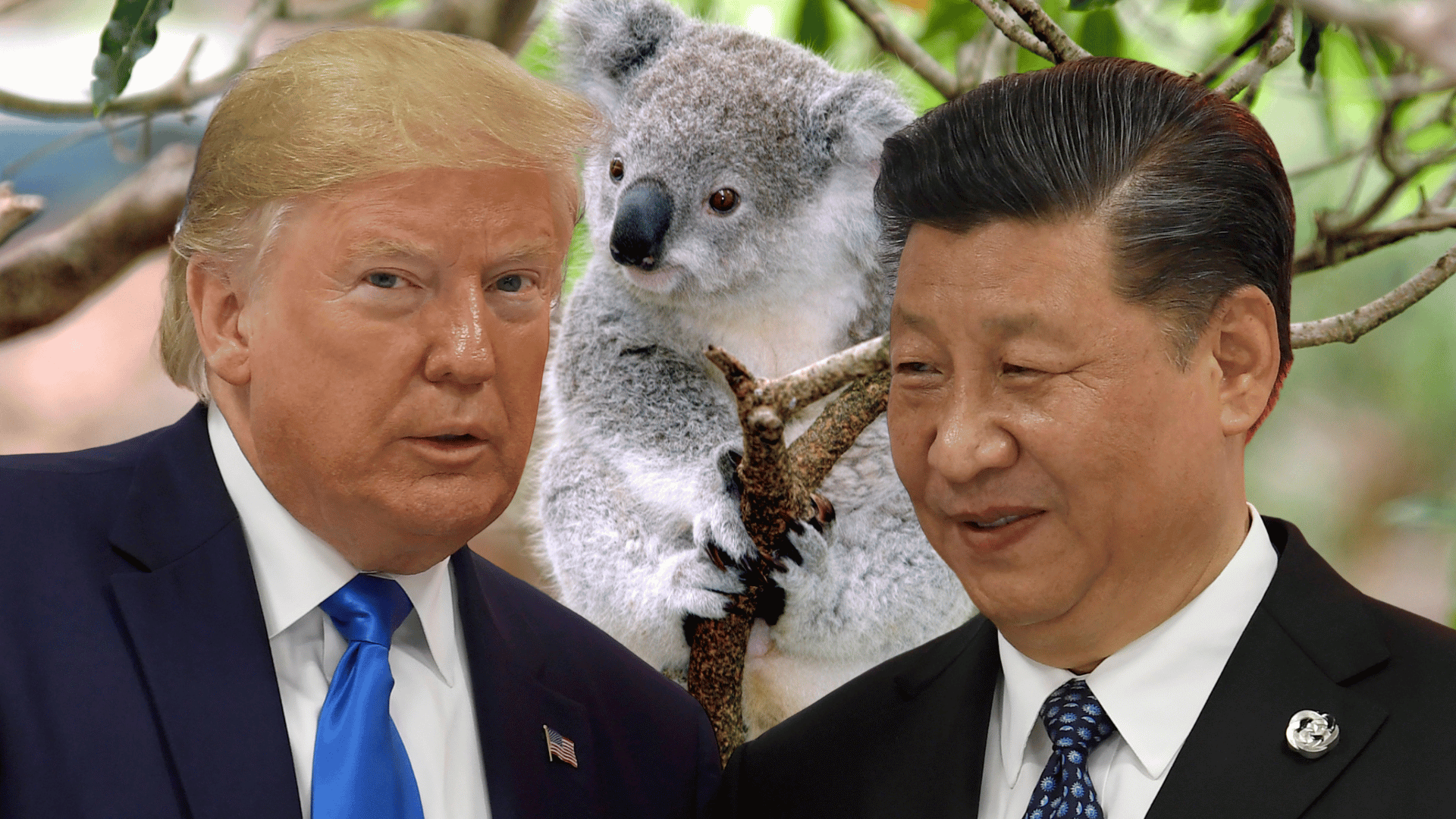

The portrait that emerges from its latest survey is that while China’s overall power still lags the United States, it is not far behind, even though the current economic slowdown is holding it back in the short term.

After the two superpowers, trailing a long way back as the next most powerful countries in the Asia-Pacific are Japan, India, Russia and then Australia.

Economic versus military power

The index confirms that China draws its power from its central place in Asia’s economic system, while that of the United States comes from its military capability and unrivaled regional defense networks.

Australia’s relationship with the two mirrors the dilemma facing the whole region.

The United States is far and away Australia’s main strategic partner and has been since the Second World War.

In a deal signed in March 2023, Australia is set to acquire a conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarine capability with help from the United States through the AUKUS Treaty, which also involves the United Kingdom.

This was followed by plans to station more U.S. forces in Australia, especially in air bases in northern and western Australia. There are also moves to increase cooperation between both countries in space, speed up efforts for Australia to develop its own guided missile production capability and work with the United States to deepen security relationships with other countries in the region — most notably Japan.

This comes as Australia has been working hard to get trade restrictions eased with China after it imposed tariffs on a range of Australian products in 2020 during a standoff with the previous government.

Dining with Joe and Jinping

China is still Australia’s largest two-way trading partner in goods and services, accounting for almost one third of its trade with the world. Two-way trade with China grew 6.3% in 2020-21 to A$267 billion (about US$180 billion), mostly due to the coal and iron ore sectors.

So as it stands, Australia’s security relies on the United States but its economic prosperity is heavily influenced by China.

It’s no surprise then that Prime Minister Albanese had to walk a fine line in 2023 — going from a state dinner at the White House with U.S. President Biden on 26 October to meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping 11 days later.

Colin Heseltine, a former Deputy Head of Mission at the Australian Embassy in Beijing and now senior advisor for independent think tank Asialink, said Australia is in a conundrum over China.

“Australia’s major trading partner is also perceived as our No.1 security threat,” he said.

Normalizing relations before an abnormal U.S. election

Heseltine believes there is a mood of cautious optimism about the growing relationship between Australia and China since the election of the Albanese government, but expects the future will not be completely free of headwinds.

In the end, Australia, like many other nations in the region, is pragmatically making the situation work. It has seen relations with Beijing normalize, or as some prefer to describe it, stabilize.

As for the United States, relations between Canberra and Washington remain vibrant and strong.

The next big issue for Australia in managing this twin policy of improving ties with the Asia-Pacific’s two diverse superpowers could well be the 2024 U.S. presidential election — who wins it and if China features in it.

And those things are outside its control.

Three questions to consider:

1. What is the emerging dilemma facing most democratic nations in the Asia-Pacific region?

2. Is China likely to overtake the United States as the Asia-Pacific’s major superpower anytime soon?

3. What is the biggest threat to the current status quo facing nations in the region?

-

News Decoder helps launch digital student journalism tool

Gathering and assessing the quality of information is one of the most effective ways to develop media literacy, critical thinking and effective communication skills. But without guidance, too many young people fail to question the reliability of visual images and overly rely on the first results they find on Google.

That’s why News Decoder has been working with the Swedish nonprofit, Voice4You, on a project called ProMS to create a self-guided digital tool that guides students in writing news stories.

The tool, called Mobile Stories, is now available across Europe. It takes students step-by-step through the journalistic process. Along the way, they gain critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding about the information they find, consume and share.

It empowers students to develop multimedia stories that incorporate original reporting for school, community or global audiences, with minimal input from educators. It comes with open-access learning resources developed by News Decoder.

After a decade of success in Sweden, Voice4You partnered with News Decoder to help make the tool available across Europe and the globe. Throughout the ProMS project, new English language content suitable for high schoolers was developed and piloted in 21 schools in Romania, Ireland and Finland. The Mobile Stories platform has demonstrated remarkable potential in building student confidence and media and information literacy by providing a platform and an opportunity to produce quality journalism.

From story pitch to publication

Using the new international version of Mobile Stories, students have already published 136 articles on mobilestories.com, with another 700 currently in production. Their topics range from book reviews and reporting from local cultural events to in-depth feature articles on the decline in young people’s mental health and child labor in the fast fashion industry.

“The tool looks like a blogging platform and on every step along the way of creating an article, students can access learning materials including video tutorials by professional journalists from around the world, articles and worksheets,” said News Decoder’s ProMS Project Manager Sabīne Bērziņa.

Some of these resources, such as videos and worksheets are open access, available to all.