Degree apprenticeships, programs that let students earn a college degree while gaining paid work experience, are a fast-growing model in education and workforce development. But new research from the think tank New America finds access to them remains limited and uneven.

A report released this month by New America’s Center on Education & Labor found that about 350 institutions nationwide offered nearly 600 degree apprenticeship programs integrated with associate, bachelor’s or master’s degrees, preparing students for 91 different occupations.

Among institutions that offer them, degree apprenticeships are concentrated in a small number of fields, with K–12 teaching and registered nursing accounting for the largest share.

Ivy Love, a senior policy analyst at New America, said degree apprenticeships are especially valuable for states facing teacher or nurse shortages.

“These are two rapidly growing professional areas for degree apprenticeships,” Love said. “There is an opportunity to make these paths into these professions more accessible.”

Degree apprenticeships combine paid work experience, on-the-job training, employer-aligned classroom instruction and recognized credentials with an associate, bachelor’s or master’s degree. Learners participate in work-based learning while completing coursework—known as related technical instruction—at a college or university that aligns with what they are learning on the job.

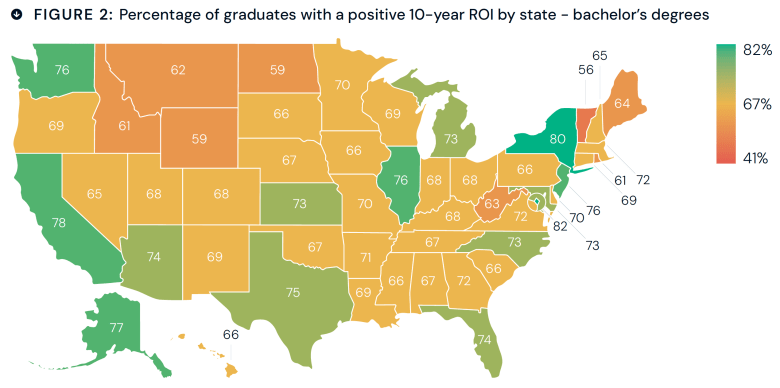

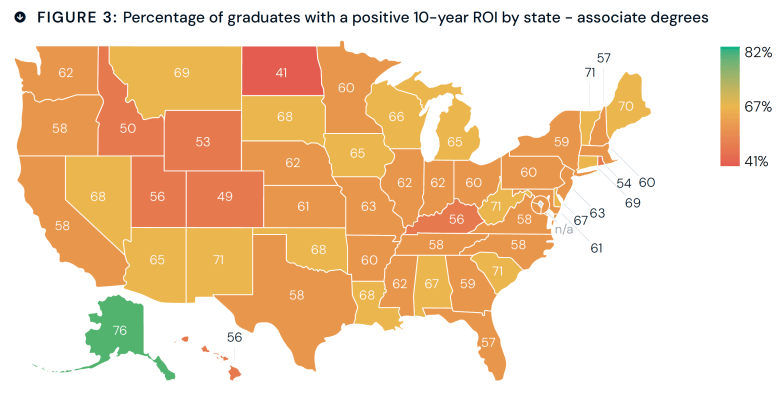

These programs are emerging at a moment of growing skepticism about the value of a college degree. In New America’s Varying Degrees 2025 survey, just 52 percent of adults—a slim majority—said a postsecondary credential is the minimum level of education they believe a close family member needs to ensure financial security.

At the same time, New America found that earning a postsecondary degree remains the surest path to economic stability and family-supporting wages. In 2024, households with two adults needed to earn more than $100,000 a year to support two children—a level of pay that typically requires at least an associate degree, the report said.

Lancy Downs, a senior policy analyst at New America, said one story that stood out in the report came from an administrator at an Alabama community college where more than half the students attend part-time. The administrator explained that this is because school is optional, but work is not.

“We see [degree apprenticeships] as an effective way to upskill people into higher-paying jobs with more upward mobility,” Downs said. “They also help bring more people into professions well suited for this model, allowing students to earn a paycheck, attend school and take on minimal debt at the same time.”

The findings: The report found that programs that prepare K–12 teachers made up 156 of the nearly 600 degree apprenticeships identified, while registered nursing programs accounted for 51. Other positions represented include electro-mechanical and mechatronics technologists and technicians, electricians, and industrial engineering technologists and technicians.

With the exception of teaching, most degree apprenticeship opportunities are concentrated at the associate-degree level. Two-thirds of the programs awarded associate degrees, 29 percent awarded bachelor’s degrees and 4 percent awarded master’s degrees, according to the report. Most associate-level credentials were associate of applied science degrees.

Love said occupational requirements are the main factor driving these patterns: Careers in teaching typically require a bachelor’s degree, while nursing careers can be started with an associate degree.

“Community colleges have been really involved in degree apprenticeships, many of them for quite some time,” Love said. She noted that although some universities offer degree apprenticeships as well, community colleges’ “workforce orientation” gives them more familiarity with the model, and two-year institutions are more likely to have close connections to employers in technical fields.

The report also found that rural and small-town colleges are disproportionately represented among institutions offering teacher apprenticeships, suggesting degree apprenticeships in teaching are shaped by local workforce needs.

Downs said she suspects the prevalence of the “grow-your-own” model in teacher training explains this pattern.

“It’s possible that the prevalence of those already in teaching contributed to the overrepresentation in many rural communities,” Downs said.

The implications: Downs said degree apprenticeships’ small program size, reliance on public funding and other structural factors must be addressed for programs to succeed.

“We don’t really fund degree apprenticeships the same way we fund K–12 schools or even higher education,” Downs said, noting that most funding comes from “one-off” federal grants.

“More funding is needed to get [degree apprenticeship] programs up and off the ground and figure out how to run them sustainably,” she said.

Beyond funding, Downs said the programs also need to be thoughtfully designed to meet the needs of the students they serve.

“If you can get credit for what you’re learning on the job, you don’t have to sit in a classroom to learn the same thing again. It makes the programs more efficient for learners and employers, which we support,” Downs said.

Love said the degree apprenticeship model allows students to combine the benefits of work and education in a single pathway.

“This is a ‘yes, and’ strategy,” Love said. “Through [degree apprenticeship] programs, we hope to learn more in the coming years about how they open pathways to important professions while giving people another option that brings the best of both worlds together.”

Get more content like this directly to your inbox. Subscribe here.