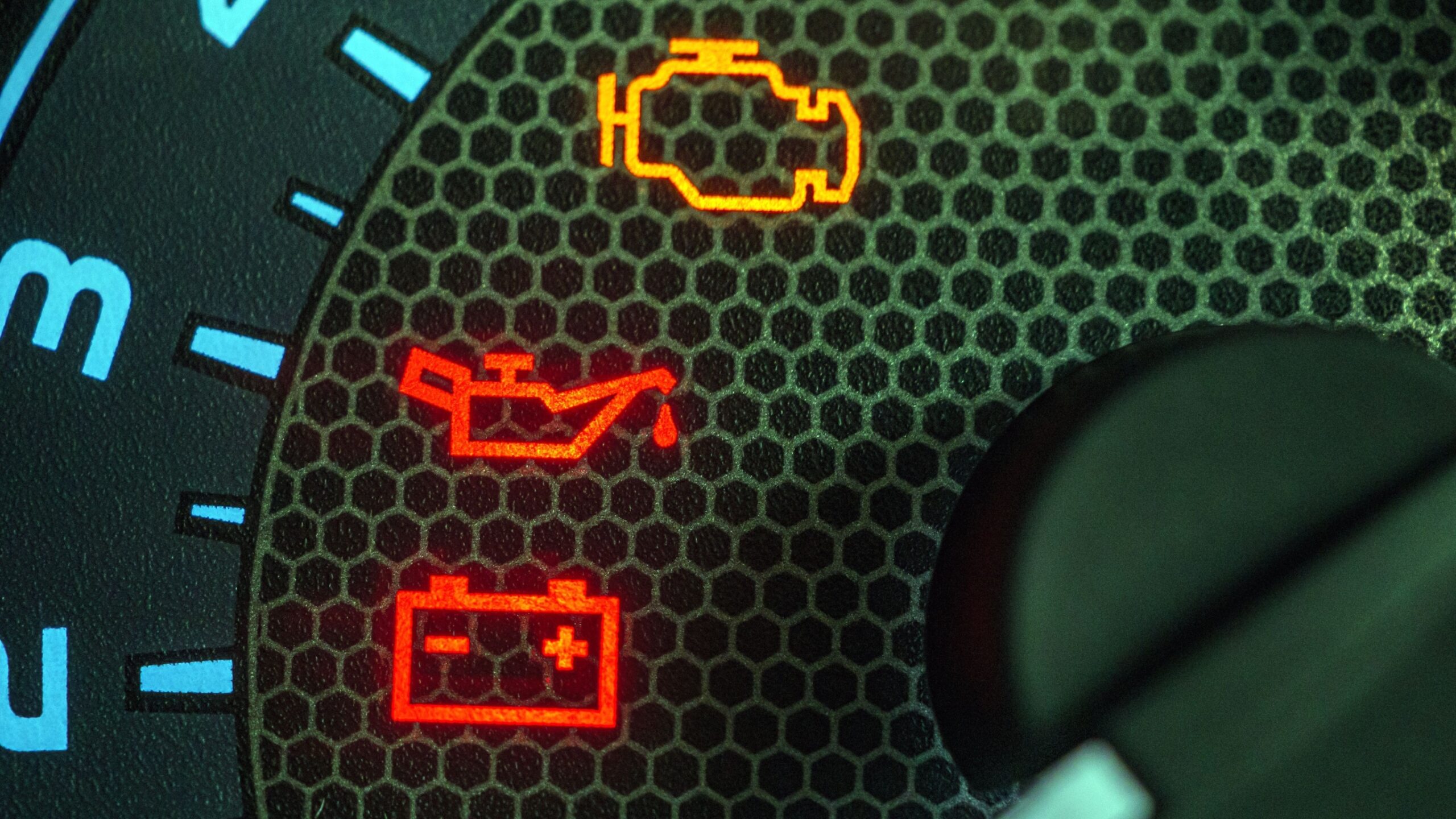

Dashboards light up with warning signals weeks into term, yet intervention often comes too late—if at all.

Despite significant investment in learner analytics and regulatory pressure to meet an 80 per cent continuation threshold for full-time undergraduates, universities consistently struggle to act when their systems flag at-risk students.

This implementation gap isn’t about technology or data quality. It’s an organisational challenge that exposes fundamental tensions between how universities are structured and what regulatory compliance now demands.

The Office for Students has made its expectations clear: providers must demonstrate they are delivering positive outcomes, with thresholds of 80 per cent continuation and 75 per cent completion for full-time first degree students. Context can explain but not excuse performance below these levels. Universities are expected to identify struggling students early and intervene effectively.

Yet most institutions remain organised around systems designed for retrospective quality assurance rather than proactive support, creating a gap between regulatory expectations and institutional capability.

The organisational challenge of early intervention

When analytics platforms flag students showing signs of disengagement—missed lectures, incomplete activities, limited platform interaction—institutions face an organisational challenge, not a technical one. The data arrives weeks into term, offering time for meaningful intervention. But this is precisely when universities struggle to act.

The problem isn’t identifying risk. Modern analytics can detect concerning patterns within the first few weeks of term. The problem is organisational readiness: who has authority to act on probabilistic signals? What level of certainty justifies intervention? Which protocols govern the response? Most institutions lack clear answers, leaving staff paralysed between the imperative to support students and uncertainty about their authority to act.

This paralysis has consequences. OfS data shows that 7.2 per cent of students are at providers where continuation rates fall below thresholds. While sector-level performance generally exceeds requirements, variation at provider and course level suggests some institutions manage early intervention better than others.

Where regulatory pressure meets organisational resistance

The clash between regulatory expectations and institutional reality runs deeper than resource constraints or technological limitations. Universities have developed (sometimes over centuries) around a model of academic authority that concentrates judgement at specific points: module boards, exam committees, graduation ceremonies. This architecture of late certainty served institutions well when their primary function was certifying achievement. But it’s poorly suited to an environment demanding early intervention and proactive support.

Consider how quality assurance typically operates. Module evaluations happen after teaching concludes. External examiners review work after assessment. Progression boards meet after results are finalised. These retrospective processes align with traditional academic governance but clash with regulatory expectations for timely intervention. The Teaching Excellence Framework and B3 conditions assume institutions can support students before problems become irreversible, yet most university processes are designed to make judgements after outcomes are clear.

The governance gap in managing uncertainty

Early intervention operates in the realm of probability, not certainty. A student flagged by analytics might be struggling—or might be finding their feet. Acting means accepting false positives; not acting means accepting false negatives. Most institutions lack governance frameworks for managing this uncertainty.

The regulatory environment compounds this challenge. When the OfS investigates providers with concerning outcomes, it examines what systems are in place for early identification and intervention. Universities must demonstrate they are using “all available data” to support students. But how can institutions evidence good faith efforts when their governance structures aren’t designed for decisions based on partial information?

Some institutions have tried to force early intervention through existing structures—requiring personal tutors to act on analytics alerts or making engagement monitoring mandatory. But without addressing underlying governance issues, these initiatives often become compliance exercises rather than genuine support mechanisms. Staff comply with requirements to contact flagged students but lack clear protocols for escalation, resources for support, or authority for substantive intervention.

Building institutional systems that bridge the gap

Institutions successfully implementing early intervention share common organisational characteristics. They haven’t eliminated the tension between regulatory requirements and academic culture—they’ve built systems to manage it.

Often they create explicit governance frameworks for uncertainty. Rather than pretending analytics provides certainty, they acknowledge probability and build appropriate decision-making structures. This might include intervention panels with delegated authority, clear escalation pathways, or risk-based protocols that match response to confidence levels. These frameworks document decision-making, providing audit trails that satisfy regulatory requirements while preserving professional judgement.

They develop tiered response systems that distribute authority appropriately. Light-touch interventions (automated emails, text check-ins) require minimal authority. Structured support (study skills sessions, peer mentoring) operates through professional services. Academic interventions (module changes, assessment adjustments) involve academic staff. This graduated approach enables rapid response to early signals while reserving substantive decisions for appropriate authorities.

And they invest in institutional infrastructure beyond technology. This includes training staff to interpret probabilistic data, developing shared vocabularies for discussing risk, and creating feedback loops to refine interventions. Successful institutions treat early intervention as an organisational capability requiring sustained development, not a technical project with an end date.

The compliance imperative and cultural change

As the OfS continues its assessment cycles, universities face increasing pressure to demonstrate effective early intervention. This regulatory scrutiny makes organisational readiness a compliance issue. Universities can no longer treat early intervention as optional innovation—it’s becoming core to demonstrating adequate quality assurance. Yet compliance-driven implementation rarely succeeds without cultural change. Institutions that view early intervention solely through a regulatory lens often create bureaucratic processes that satisfy auditors but don’t support students.

More successful institutions frame early intervention as aligning with academic values: supporting student learning, enabling achievement, and promoting fairness. They engage academic staff not as compliance officers but as educators with enhanced tools for understanding student progress. This cultural work takes time but proves essential for moving beyond surface compliance to genuine organisational change.

Implications for the sector

The OfS shows no signs of relaxing numerical thresholds—if anything, regulatory expectations continue to strengthen. Financial pressures make student retention more critical. Public scrutiny of value for money increases pressure for demonstrable support. Universities must develop organisational capabilities for early intervention not as a temporary response to regulatory pressure but as a permanent feature of higher education.

This requires more than purchasing analytics platforms or appointing retention officers. It demands fundamental questions about institutional organisation: How can governance frameworks accommodate uncertainty while maintaining rigour? How can universities distribute authority for intervention while preserving academic standards? How can institutions build cultures that value prevention as much as certification?

The gap between early warning signals and institutional action is an organisational challenge requiring structural and cultural change. Universities investing only in analytics without addressing organisational readiness will continue to struggle, regardless of how sophisticated their systems become. These aren’t simple changes, but they’re necessary for institutions serious about supporting student success rather than merely measuring it.

The question facing universities isn’t whether to act on early warning signals—regulatory pressure makes this increasingly mandatory. The question is whether institutions can develop the organisational capabilities to act effectively, bridging the gap between data and decision, between warning and intervention, between regulatory compliance and educational values.

Those that cannot may find themselves not just failing their students but failing to meet the minimum expectations of a regulated sector.