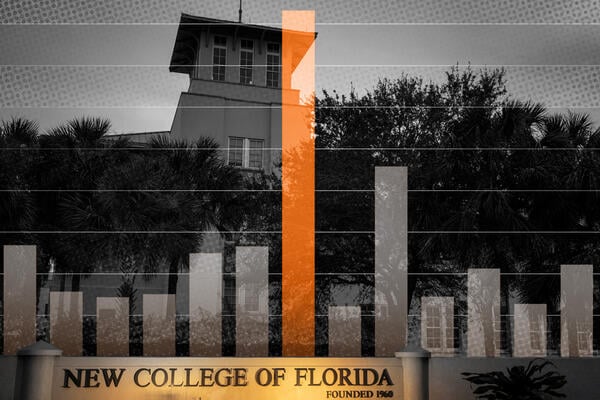

New College spent $83,207 per student in fiscal year 2024, the highest among state universities.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Thomas Simonetti/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Nearly three years into a conservative overhaul of New College of Florida, costs are adding up as the operating expenses per student dramatically outpace other State University System of Florida members.

Data presented at Thursday’s Florida Board of Governors offers the clearest breakdown so far of what New College is spending per student compared to 11 other system members. NCF spent $83,207 per student in fiscal year 2024, the highest among state universities.

The University of Florida, a major research institution, was the next highest at $45,765 per student, while the lowest was the University of Central Florida at $12,172 per student, according to data compiled by the Florida Department of Government Efficiency.

New College and UF also had the highest number of administrators per 100 students. New College had 33.3 administrators per 100 students while UF had 26.9. Others in the system ranged from a low of 4.6 administrators per student at UCF to 12.6 at the University of South Florida.

Silence on Spending

Now, despite support from Republican governor Ron DeSantis—who appointed a slate of conservative trustees in early 2023 and tasked them with reimagining the small liberal arts college—NCF is facing growing scrutiny over soaring operating expenses from alumni and other community members. But the Florida Board of Governors, which is appointed by DeSantis, had little to say when presented with the numbers at Thursday’s meeting.

Eric Silagy, who has been the board member most critical of NCF’s spending and has previously pressed college leadership on the matter, was the only one to offer remarks about the disparity. In limited comments, Silagy thanked Ben Watkins, director of the Florida Division of Bond Finance, for the presentation, which he said made university spending clear.

Now, Silagy said, “there can be no question anymore about what the numbers really are.” He added that Florida’s DOGE data will allow the Board of Governors to “address outliers where it’s not working” and determine how to reach “better outcomes for the students and the taxpayers.”

Silagy had clashed with NCF President Richard Corcoran, a former Republican lawmaker, on how much New College spends per student in past meetings. Silagy had estimated NCF spent $91,000 per student, while Corcoran initially said the number was closer to $68,000 per head. Corcoran later backtracked, agreeing the figure was between $88,000 and $91,000 per student.

That spending has ticked up even as critics in the community and state legislature are growing, and as the college saw its place in U.S. News & World Report rankings fall nearly 60 spots since the takeover. The rankings are highly valued by Florida lawmakers and system officials.

Asked about DOGE’s findings, a New College spokesperson said issues preceded current leadership.

“Thanks to Governor DeSantis and the Florida Legislature making a bold move to appoint new leadership with clear goals, the impact of New College’s revitalization is already visible with enrollment surpassing 900 students for the first time in history,” New College spokesperson James Miller wrote in an emailed statement to Inside Higher Ed. “As enrollment growth continues to skyrocket, cost-per-student and cost-per-graduate metrics will be one of the lowest of all top liberal arts schools in the country.”

Other Meeting Notes

Thursday’s board meeting also included an update from UCF President Alexander Cartwright, who told FLBOG members that the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) had approved the university for initial accreditation, amid an effort to switch accreditors that had been underway since 2023.

UCF, like other state institutions, sought to switch from Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to another accreditor, following a change to state law in 2022 that mandated the switch after state officials clashed with the organization over various issues.

Cartwright said he received the news from HLC just hours earlier during the meeting.

State University System of Florida Chancellor Ray Rodrigues credited Cartwright for his work on the effort and criticized the Biden administration for allegedly slow-walking the process.

Rodrigues argued that the Biden administration “did not want to see reform in the area of accreditation” and “put up barriers and obstacles to states like Florida and universities like UCF” who were seeking to change accreditors while following Department of Education guidelines.

The Florida Board of Governors also approved a policy change that will now require professors at all state universities to publicly post course materials. The policy will require “universities to post current syllabi for all courses and course sections offered for the upcoming term” at least 45 days before the first day of class. Those materials will then remain online for at least five years.

That policy change, which has been the subject of recent media coverage highlighting faculty concerns about being targeted for course content, was passed as part of the consent agenda with no public discussion. No faculty members spoke about the policy change during the public comment portion of the meeting despite concerns expressed by professors in recent coverage.

The board did not take action or discuss a directive from DeSantis late last month to “pull the plug” on hiring workers on H-1B visas at state universities amid concerns that such hires are taking jobs that could otherwise be filled by Floridians. (However, critics have noted such jobs are often highly specialized and hard to fill.) The board plans to consider that directive in January.