NASHVILLE, Tenn.—Talk of what’s possible with AI permeated conversations this week among the 7,000 attendees at Educause, the sector’s leading education-technology conference. But amid the product demos, corporate swag and new feature launches, higher ed’s technology and data leaders expressed caution about investing in new tech.

They said that budget constraints, economic uncertainty and understaffed technology teams were forcing them to seek a clear return on investment in new tools rather than quick-fix purchases. And as tech leaders look to the coming year, they say the human side of data, cybersecurity and AI will be the focus of their work.

Educause researchers at the event announced the 2026 Educause Top 10, a list of key focus areas they compiled based on interviews with leaders, expert panel recommendations and a survey of technology leaders at 450 institutions. The results underline how uncertainty around federal funding, economic instability and political upheaval is making it hard for leaders to plan.

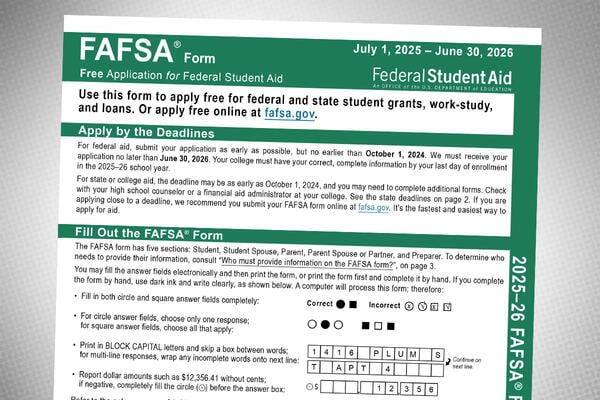

The 2026 Educause Top 10

- Collaborative Cybersecurity

- The Human Edge of AI

- Data Analytics for Operational and Financial Insights

- Building a Data-Centric Culture Across the Institution

- Knowledge Management for Safer AI

- Measure Approaches to New Technologies

- Technology Literacy for the Future Workforce

- From Reactive to Proactive

- AI-Enabled Efficiencies and Growth

- Decision-Maker Data Skills and Literacy

For example, No. 6 on the list is “Measured Approaches to New Technologies.” Leaders say they intend to “make better technology investment decisions (or choosing not to invest) through clear cost, ROI and legacy systems assessments.”

Presenting the top 10 in a cavernous ballroom in the Music City conference center, Mark McCormack, senior director of research and insights at Educause, said leaders feel pressure to make smart investments and stay on top of rapid advancements in technology. “The technology marketplace is evolving so quickly and institutions feel a pressure to keep up, but that pressure to keep up can lead to less optimal approaches to technology purchasing and implementation,” he said.

“From some of our other Educuase research we know that quick fixes and reactive purchases often lead to technical debt and poor interoperability and additional strains on our technology teams,” he added. “That’s just not sustainable, especially with our tight budgets and our capacity, so we need to make decisions based on a clear understanding of cost and value.”

No. 3 on the list, “Data Analytics for Operational and Financial Insights,” indicated technology leaders will respond to intensifying financial pressures through better data analysis. “Cuts to federal funding, enrollment trends, public skepticism about the value of a degree—so many of us are feeling that weight right now, and in this kind of environment our institutions are turning to data as a guide to help them navigate some complicated decisions,” McCormack said.

Data can also help colleges identify priority areas for investment, such as enrollment targets, compliance requirements or areas of programmatic growth, he noted. “But our data can also guide conversations about where to scale back, and we need to be able to distinguish between high-impact priorities and areas that may no longer align with the institution’s direction.”

Commenting on the top 10, Brandon Rich, director of AI enablement at the University of Notre Dame, said his institution is using AI to navigate tight budgets. “With the budget challenges we face, we see AI as a possible way to move forward and create efficiencies,” he said during a mainstage panel.

Speaking with Inside Higher Ed, Nicole Engelbert, vice president of product strategy for student systems at Oracle, said colleges are reviewing their tech ecosystems more critically. “Institutions are looking to streamline, consolidate, shop their closet, because any dollar spent on extraneous technology is a dollar that isn’t going to be spent for research, student aid, recruitment, classes, faculty—all the things that make an institution healthy and vibrant,” she said.

She expects the current political and economic climate will dissuade institutions from taking on expensive, transformational projects. “Making big changes on your payroll, on your general ledger, on your student enrollment takes huge amounts of psychic energy from a large population, and that population right now is very weary. They’re exhausted by the last year,” she said.

One silver lining of higher ed’s financial uncertainty could be a shift toward more tactical forward planning, Engelbert said. “I hope there’s this new period where we look at transformation projects or technology projects more strategically, more critically,” she said.

Collective Will, Individual Capabilities

Other priorities on the Educause top 10 look similar to those from previous years: Improved cybersecurity, better data and data governance, and harnessing the power of AI are issues that have appeared on the list for the past five years.

But Educause researchers say this year’s study shows leaders’ focus has shifted from infrastructure and platforms to the humans working with these systems. They break the list into two themes: collective will—connecting resources and knowledge across departments to “shape a shared institutionwide perspective”—and individual capabilities, or training and empowering people to realize the “net benefits” of the technologies and data on campus.

“The thing that we saw that was very different is that … even as technology is skyrocketing, changing everything we do, we as higher education need to remember our humanity and lead with that because that’s what makes us resilient,” said Crista Copp, vice president of research at Educause.

No. 1 on the list is “Collaborative Cybersecurity,” reflecting institutions’ urgency to safeguard their expanding digital borders.

“The ecosystem is becoming a lot more distributed across devices and locations. That person who’s using their device logging in to that system from, you know, a coffee shop or wherever, they’re becoming more and more important to be educated and equipped to do that safely,” McCormack told Inside Higher Ed.

“The other thing that did come up is an acknowledgment that as our tools are becoming more sophisticated … those threat actors are becoming more sophisticated as well.”

Institutional data and how it is managed will also be a priority for technology leaders in 2026, according to the list. “Data Analytics for Operational and Financial Insights” is No. 3, “Building a Data-Centric Culture Across the Institution” is No. 4, and “Decision-Maker Data Skills and Literacy” comes in at No. 10.

Copp said these issues suggest institutions will be tackling data from different angles. “It’s this triad of ‘Oh my gosh, we have all this information. And we don’t have it organized properly. We don’t know how to interpret it properly. And then we don’t know what to do with it,” she said. “I found it really interesting that … we saw three sides of the same thing.”

AI-related issues also appear three times on the list: “The Human Edge of AI” at No. 2, “Knowledge Management for Safer AI” at No. 5 and “AI-Enabled Efficiencies and Growth” at No. 9. The growing focus on improving AI across institutions also represents a shift in what’s needed in the higher education workforce.

“I think everyone, regardless if you’re in higher education or not, [is] facing workforce changes. And part of that is, who do we want to be? And we need to define [that],” she said. “No. 2 [on the list] … is the human edge of AI and it’s, ‘Although we expect you to use AI, we want you to come as a person first, because that’s what education is all about.’”