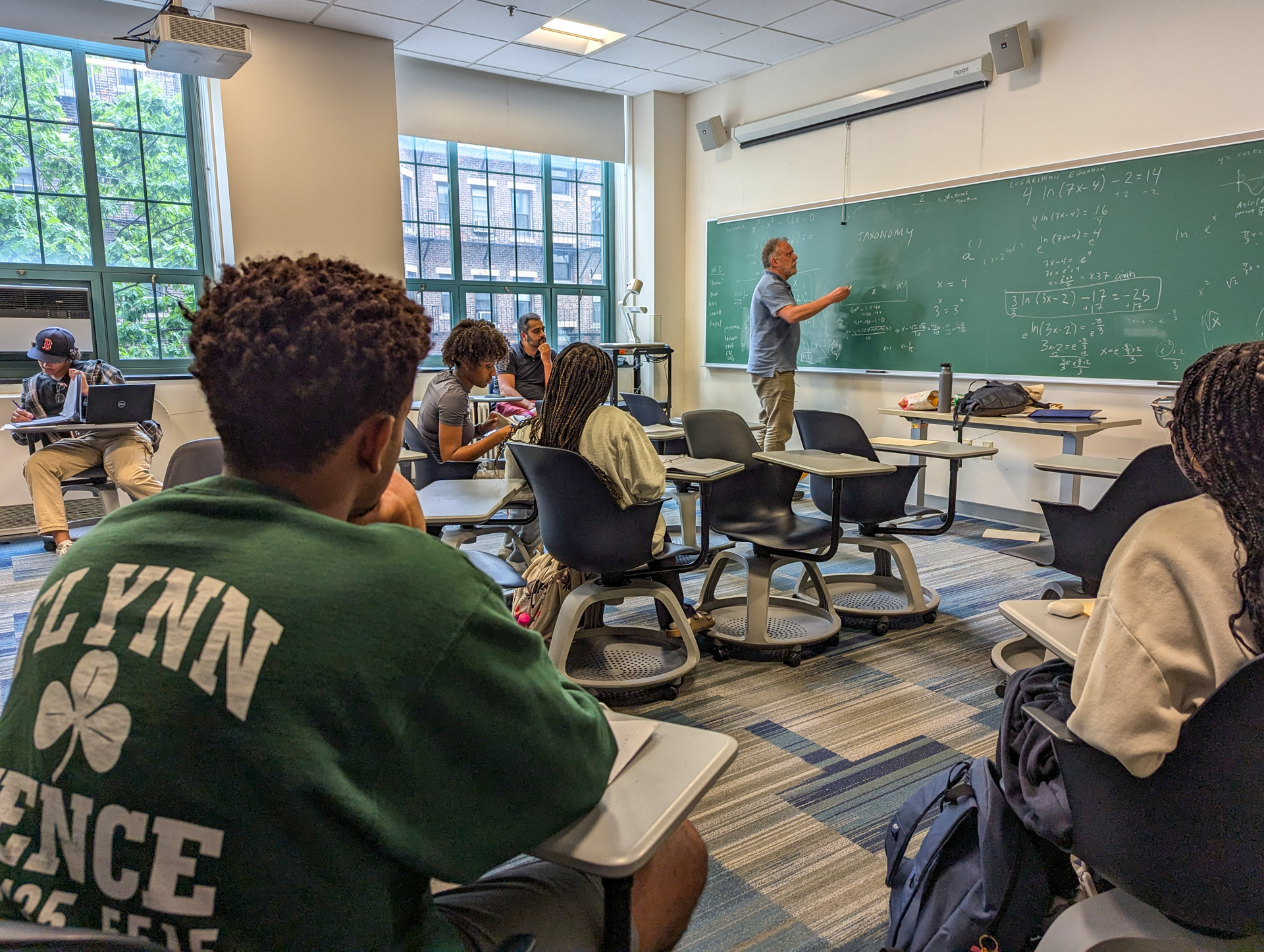

Walk into almost any office on a campus right now and you’ll hear the same thing: “We’re experimenting with AI.” Someone is drafting social posts in ChatGPT. Someone else is piloting a chatbot for admissions FAQs. Another is tinkering with predictive models in the CRM.

These efforts are well intentioned, but nearly three years into the ready availability of generative AI tools, higher ed needs to understand that dabbling isn’t enough anymore.

Higher education is under immense pressure. From the demographic cliff to the search cliff, the drop in international enrollment to the decline in the public perception of higher education, our industry is fraught with challenges. When we combine these challenges with the escalating expectations from students and families and the “experience economy,” we’re setting ourselves up to fall dangerously behind.

AI can be part of the solution to those challenges. But if we limit ourselves to scattered experiments, we risk wasting resources and missing the opportunity to use AI as a true strategic advantage.

The Risks of Dabbling

When AI adoption is fragmented, several challenges emerge:

- Duplicated work and tool sprawl. Different units adopt different tools, leading to confusion, inconsistent data and hidden costs.

- Inconsistent brand voice. Without shared guidelines, AI-generated content can erode the consistency of a university’s storytelling.

- Ethical blind spots. Dabbling often means no governance. Sensitive student data can inadvertently end up in AI tools.

- Staff frustration. When AI feels like extra work instead of a supportive tool, teams become skeptical. That makes adoption harder later.

- Lost momentum. When experiments aren’t connected to measurable outcomes, leadership may conclude that AI “doesn’t work here.”

The paradox is this: Dabbling may feel safer, but it is actually riskier than intentional adoption.

What Intentional Adoption Looks Like

Intentional adoption doesn’t mean rushing into automation or replacing staff. It means aligning AI with institutional goals, building literacy across teams, creating ethical guardrails and sharing results transparently.

Take admissions chatbots. Many institutions piloted them to handle high-volume FAQs. Some fizzled out because there was no plan for training, governance or integrating insights back into the enrollment strategy. But at campuses where chatbots were tied to yield goals, tested with student input and connected to human follow-up, they became powerful tools for reducing melt and increasing student satisfaction.

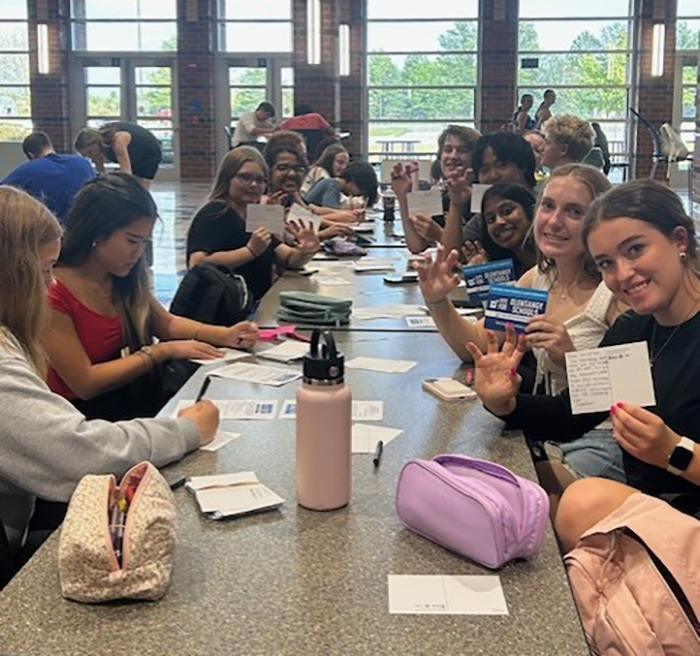

Or consider content creation. I’ve seen marketing teams use AI to repurpose one student story into dozens of assets, like email copy, Instagram posts, video scripts. When done thoughtfully, this allowed teams to do more with the same staff, freeing time for higher-level strategy. When done haphazardly, it can lead to a flood of off-brand content that students recognize as AI, eroding trust.

A Framework for Readiness

So how can institutions move from dabbling to adopting? One approach I use with teams is the AI Maturity Matrix.

The matrix evaluates readiness across six dimensions—vision, leadership support, skills, governance, collaboration, and technology—and places organizations on a five-stage curve:

- Nascent: AI is barely leveraged, or individual experiments happen in silos.

- Developing: Small pilots exist but aren’t connected to strategy.

- Scaling: Multiple projects are coordinated and tied to goals.

- Optimized: AI is part of daily workflows, with governance and training in place.

- Transformational: AI is a true differentiator, fueling innovation and efficiency across the institution.

Most higher ed teams that I speak with fall in the second and third categories. They are experimenting and maybe scaling, but without the governance or strategy to optimize. The matrix helps teams see their starting point clearly and, more importantly, identify what it will take to get to the next stage.

The key is not to leap from nascent to transformational overnight, but instead move steadily, stage by stage, building capacity along the way.

A Call to Action for Higher Ed Leaders

The issue isn’t whether higher education will use AI; it’s whether we’ll use it well.

If you’re leading a team, here are three questions to start with:

- Do we know where we stand on the AI maturity curve?

- Are our current experiments connected to our overarching goals?

- What’s one step we could take in the next 30 days to build intentional capacity?

These questions are urgent. Students are already comparing their campus experience to the seamless, personalized interactions they get from Amazon, Spotify or Netflix. Faculty and staff are already using AI tools in their personal lives, whether institutions acknowledge it or not. The longer we leave AI adoption uncoordinated, the greater the gap grows between what higher ed delivers and what students expect.

I still hear from people who believe AI is a passing fad. Meanwhile, the world around us is shifting in significant ways that have the potential to leave us far behind. Institutions must approach their AI adoption with clarity and intentionality. Those that treat it as a novelty risk being left behind.

The time for dabbling is over. The time for intentional adoption is now.