by Jackie Mader, The Hechinger Report

December 10, 2025

Close to 40,000 foreign-born child care workers have been driven out of the profession in the wake of the Trump administration’s aggressive deportation and detainment efforts, according to a new study by the Better Life Lab at the think tank New America. That represents about 12 percent of the foreign-born child care workforce.

Child care workers with at least a two-year college degree are most likely to be leaving the workforce, as well as workers who are from Mexico, a demographic targeted by ICE, or those who work in center-based care, the left-leaning think tank found. The disruption has worsened an already deep shortage of child care staffers, threatening the stability of the industry and in turn is contributing to tens of thousands of U.S.-born mothers dropping out of the labor market because they don’t have reliable child care.

In addition to workers facing detainment or deportation, many people are staying home to avoid situations where they may encounter Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the report found. Agents are detaining people who have not traditionally been the focus of ICE actions, including those following legal pathways like asylum seekers and green card applicants. Child care centers were once considered “sensitive locations” exempt from ICE enforcement, but the White House rescinded that in January. In at least one example, a child care worker was detained while arriving for work at a child care program.

“What’s different now is the ferocity of the enforcement,” said Chris Herbst, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Public Affairs and one of the authors of the report, in an interview with The Hechinger Report. “ICE is arresting far more people, the number of deportations has risen dramatically,” he added. “People are scared out of their minds.”

Related: Young children have unique needs and providing the right care can be a challenge. Our free early childhood education newsletter tracks the issues.

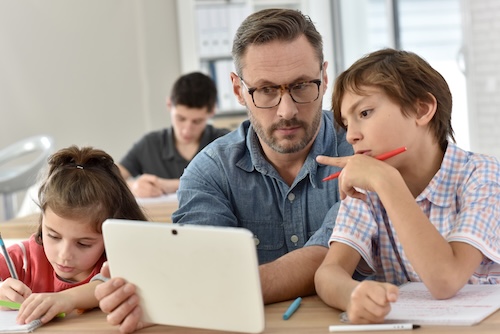

America has long relied on immigrants to fill hard-to-staff caregiving positions and enable parents to work. Across the country, around 1 in 5 child care workers is an immigrant. In Florida and New York, immigrants account for nearly 40 percent of the child care workforce. One study that compared native-born and immigrant child care workers found that nearly 64 percent of immigrants had a two- or four-year college degree, compared to 53 percent of native-born workers. The study also noted that immigrant workers are more likely than native-born workers to have child development associate credentials and to invest in professional development activities.

Overall, the child care industry supports more than $152 billion in economic activity.

In Wisconsin, Elaine, the director of a child care center, said her program has benefited greatly from a Ukrainian immigrant who has been teaching there for two years, ever since arriving in the United States as part of a humanitarian parole program. (The Hechinger Report is not using Elaine’s last name or the city where her child care center is located because she fears action by immigration enforcement.) Elaine’s center has experienced a teacher shortage for the past 13 years, and the immigrant, who has a college degree and past experience in social services, has been a steady presence for the children there.

“She’s their consistent person. She spends more time than a lot of the parents do with the children during their waking hours,” Elaine said. “She’s there for them, she’s loving, she provides that support, that connection, that security that young children need.”

In January, the Trump administration suspended the Uniting for Ukraine program, which allowed Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion to live and work in the United States for two years. While the program later opened up a process to apply for an extension, Elaine’s employee has encountered delays, like many others.

The teacher’s parole expired this month. Under the law, she is now supposed to return to Ukraine, where her home city in southeast Ukraine is still under attack by Russian forces.

Elaine fears what will happen if the center loses her. “As a business, we need her. We need a teacher we can count on,” Elaine said. “For our teachers’ mental health, to have her leave and knowing where she would go would be really difficult.”

Elaine has decided to allow the employee to keep working, and is appealing to state lawmakers to help extend her stay. Several parents have also joined in the effort, writing letters to Democratic U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin telling her how much their children love the teacher — and how important she is to the local economy. One factor in granting an extension is that the person offers a “significant public benefit” to the country.

The authors of the new report found immigrants are not the only caregivers affected by ICE enforcement this year. There has also been a drop in U.S.-born child care workers in the industry, especially among Hispanic and less-educated caregivers. This could be the result of a “climate of fear and confusion” surrounding enforcement activity, according to the report, as well as a “perceived pattern of profiling or discriminatory enforcement practices.”

“These deportations have been sold under the theory that they are going to be a boon for U.S.-born workers once we sort of unclog the labor market by removing large numbers of undocumented immigrants,” Herbst said. “We’re finding at least in the child care industry, and at least in the short run, that appears not to be the case.” Some foreign-born and U.S.-born workers have different skills and do not seem to be competing for the same caregiving jobs, he added.

Not all workers are leaving the caregiving industry altogether. Some immigrants are shifting to work as nannies or au pairs, Herbst said, “finding refuge” in private homes where they are less likely to come into contact with state child care regulators or be part of formal wage systems. (Already, an estimated 142,000 undocumented immigrants work as nannies and personal care or home health aides nationwide.) That contact with regulators and other authorities may be a reason why center-based early childhood educators are leaving the field in greater proportions now, Herbst said.

These findings come at the end of a difficult year for the child care workforce, which has long been in crisis due to dismally low pay and challenging work conditions. More than half of child care providers surveyed this year by the RAPID Survey Project at Stanford University reported experiencing difficulty affording food, the highest rate since the survey started collecting data on provider hunger in 2021. Other recent reports have found child care providers are at a higher risk for clinical depression, and in some cities an increasing number are taking on part-time jobs to make ends meet.

Across the country this year, early childhood providers have seen drops in enrollment as families pull their children out of schools and programs to avoid ICE. Child care centers are losing money and finding that some staff members are too scared to come to work or have lost work authorization after the administration ended certain refugee programs. Many child care workers have taken on additional roles driving children to and from care, collecting emergency numbers and plans for children in their care in case parents are detained and dropping off food for families too scared to leave their homes.

This story about immigration enforcement was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/immigration-enforcement-is-driving-away-early-childhood-educators/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=113841&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/immigration-enforcement-is-driving-away-early-childhood-educators/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>