On The Wonkhe Show, Public First’s Jonathan Simons offers up a critique of the way the higher education sector has been organised in recent years.

He says that despite being more pro-market than most, he’s increasingly come to the view that the sector needs greater stewardship.

He says that the theory of change embedded in the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 – that we should have more providers, and that greater choice and contestability and composition will raise standards – has worked in some instances.

But he adds that it is now “reasonably clear” that the deleterious side effects of it, particularly at a time of fiscal stringency, are “now not worth a candle”:

If we as a sector don’t start to take action on this, then the risk is that somebody who is less informed, just makes a judgment? And at the stroke of a ministerial pen, we have no franchising, or we have a profit cap, or we have student number controls. Like that is a really, really bad outcome here, but that is also the outcome we are hurtling towards, because at some point government is going to say we don’t like this and we’re just going to stop it overnight.

Some critiques of marketisation are really just critiques of massification – and some assume that we don’t have to worry about whether students actually want to study something at all. I don’t think those are helpful.

But it does seem to be true that the dominant civil service mindset defaults to regulated markets with light stewardship as the only way to organise things.

Civil servants often assume that new regulatory mechanisms and contractual models can be fine-tuned to deliver better outcomes over time. But the constant tweaking of market structures leads to instability and policy churn – and bad actors nip around the complexity.

Much of Simons’ critique was about the Sunday Times and the franchising scandal. But meanwhile, across the sector, something else is happening.

Another one

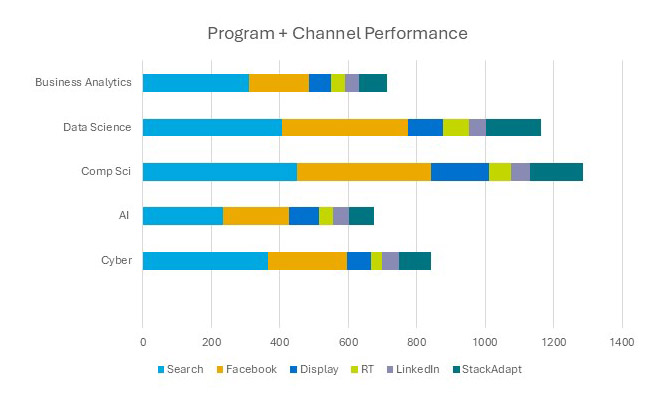

Underneath daily announcements on redundancies, senior managers and governing bodies are increasingly turning to data analytics firms to inform their academic portfolios.

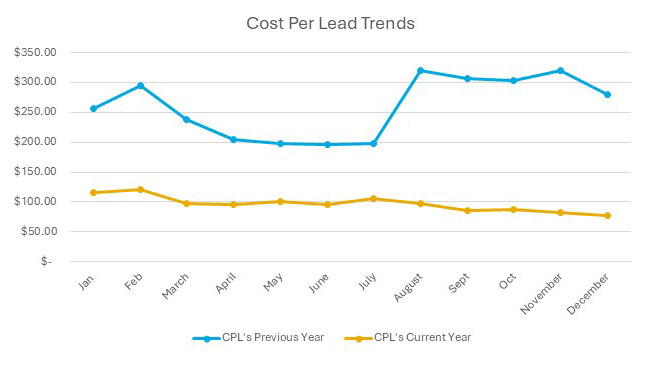

The advice is relatively consistent – close courses with low market share and poor demand projections, maintain and grow those showing high share or significant growth potential.

But when every university independently follows that supposedly rational strategy, there’s a risk of stumbling into a classic economic trap – a prisoner’s dilemma where individual optimisation leads to collective failure.

The prisoner’s dilemma, a staple of economic game theory, runs like this. Two prisoners, unable to communicate, have to decide whether to cooperate with each other or defect. Each makes the decision that seems best for their individual circumstance – but the outcome is worse for both than if they had cooperated.

I witnessed it unfold a couple of weeks ago. On a Zoom call, I watched four SU officers (under the Chatham House rule, obvs) from the same region simultaneously share that their university was planning to expand their computer science provision while quietly admitting they were “reviewing the viability” of their modern languages departments.

It did sound like, on probing, that their universities were all responding to the same market intelligence, provided by the same consultancies, using the same metrics.

Each university, acting independently and rationally to maximise its own market position, makes decisions that seem optimal when viewed in isolation. Close the underperforming philosophy department. Expand the business school. Withdraw from modern languages. Double down on computer science.

But when every university follows the same market-share playbook, the collective result risks the sector becoming a monoculture, with some subjects vanishing from entire regions or parts of the tariff tables – despite their broader societal value.

The implications of coordination failure aren’t just theoretical – they are reshaping the physical and intellectual geography of education in real time.

Let’s imagine three post-92 universities in the North East and Yorkshire each offered degrees in East Asian languages, all with modest enrolment. Each institution, following market share analysis, determines that the subject falls below their viability threshold of 40 students per cohort. Acting independently, all three close their departments, creating a subject desert that now forces students in the region to relocate hundreds of miles to pursue their interest.

The spatial mismatch of Hotelling’s Location Model means students having to travel further or relocate entirely – disproportionately affecting those from lower-income backgrounds.

And once a subject disappears from a region, bringing it back becomes extraordinarily difficult. Unlike a coffee shop that can quickly return to a high street when demand reappears, universities face significant barriers to re-entry. The sunk costs of hiring specialist staff, establishing facilities, securing accreditation, and rebuilding reputation create path dependencies that lock in those decisions for generations.

The Matthew effect and blind spots

Market-driven restructuring doesn’t affect all providers equally. Higher education in the UK operates as a form of monopolistic competition, with stratified tiers of universities differentiated by reputation, research intensity, and selectivity.

The Matthew effect – where advantages accumulate to those already advantaged – means that elite universities with strong brands and secure finances can maintain niche subjects even with smaller cohorts.

Meanwhile universities lower in the prestige hierarchy – often serving more diverse and less privileged student populations – find themselves disproportionately pressured to cut anything deemed financially marginal.

Elite concentration means higher-ranking universities are likely to become regional monopolists in certain subjects – reducing accessibility for students who can’t meet their entry requirements.

Are we really comfortable with a system where studying philosophy becomes the preserve of those with the highest A-level results, while those with more modest prior attainment are funnelled exclusively toward subjects deemed to have immediate market value?

Markets are remarkable mechanisms for allocating resources efficiently in many contexts. But higher education generates significant positive externalities – benefits that extend beyond the individual student to society at large. Knowledge spillovers, regional economic development, civic engagement, and cultural enrichment represent value that market signals alone fail to capture.

Market failure is especially acute for subjects with high social utility but lower immediate market demand. Philosophy develops critical thinking capabilities essential for a functioning democracy. Modern languages facilitate international cooperation. Area studies provide crucial cultural competence for diplomacy and global business. And so on.

When market share becomes a dominant decision criterion, broader societal benefits remain invisible on the balance sheet. The market doesn’t price in what we collectively lose when the last medieval history department in a region closes, or when the study of non-European languages becomes accessible only to those in London and Oxbridge.

And market analysis often assumes static demand curves – failing to account for latent demand – students who might have applied had a subject remained available in their region.

Demand for higher education isn’t exogenous – it’s endogenously shaped by availability itself. You can’t desire what you don’t know exists. Hence the huge growth in franchised Business Degrees pushed by domestic agents.

Collective irrationality

What’s rational for an individual university becomes irrational for the system as a whole. Demand and share advice makes perfect sense for a single institution seeking to optimise its portfolio. But when universally applied, it creates what economists call aggregate coordination failure – local optimisations generating system-wide inefficiencies.

The long-term consequences extend beyond subject availability. Regional labour markets may face skill shortages in key areas. Cultural and intellectual diversity diminishes. Social mobility narrows as subject access becomes increasingly determined by prior academic advantage. The public good function of universities – to serve society broadly, not just commercially viable market segments – erodes.

But the consequences of market-driven strategies extend beyond immediate subject availability. If we look at long-term societal impacts, we end up with a diminished talent pool in crucial but less popular fields – from rare languages to theoretical physics – creating intellectual gaps that can take generations to refill.

An innovative economy – which thrives on unexpected connections between diverse knowledge domains – suffers when some disciplines disappear from regions or become accessible only to the most privileged students.

Imagine your small but vibrant Slavic studies department closes following the kind of market share analysis I’ve explained – you lose not just courses but cross-disciplinary collaborations that generate innovative research projects. Your political science colleagues suddenly lacked crucial language expertise during the Ukraine crisis. Your business school’s Eastern European initiatives withered. A national “Languages and Security” project will boot you out as a partner.

Universities don’t compete on price but on quality, reputation, and differentiation. It creates a market structure where elite institutions can maintain prestige by offering subjects regardless of immediate profitability, while less prestigious universities face intense pressure to focus only on high-demand areas.

In the past decade, some cross-subsidy and assumptions that the Russell Group wouldn’t expand disproportionately helped. But efficiency has done what efficiency always does.

Both of the assumptions are now gone – the RG returning to the sort of home student numbers it was forced to take when the mutant algorithm inflated A-Levels in 2020.

Efficiency in market terms – optimising resources to meet measurable demand – conflicts directly with EDI and A&P goals like fair access and diverse provision. A system that efficiently “produces” large numbers of business graduates in large urban areas while eliminating classics, philosophy, and modern languages might satisfy immediate market metrics while failing dramatically at broader social missions.

And that’s all made harder when, to save money, providers are reducing elective and pathway choice rather than enhancing it.

Choice and voice

When we visited Maynooth University last year we found structures that allow students to “combine subjects across arts and sciences to meet the challenges of tomorrow.” It responds to what we know about Gen Z demands for interdisciplinary opportunities and application – and allows research-active academics to exist where demands for full, “headline” degrees in their field are low.

In Latvia recently, the minister demanded, and will now create the conditions to require, that all students be able to accrue some credit in different subjects in different institutions – partly facilitated by a kind of domestic Erasmus (responding in part to a concern about the emigration caused by actual Erasmus).

Over in Denmark, one university structures its degrees around broad disciplinary areas rather than narrowly defined subjects. Roskilde maintains intellectual diversity while achieving operational efficiency – interdisciplinary foundation years, project-based learning that integrates multiple disciplines, and a streamlined portfolio of just five undergraduate degrees.

As one student said when we were there:

The professors teaching the classes at other universities feel a need to make their little modules this or that, practical or applied as well as grounded in theory. Here they don’t have that pressure.

And if it’s true that we’re trapped in a reductive binary between lumbering, statist public services on the one hand, and lean, mean private innovative operators on the other, the false dichotomy paralyses our ability to imagine alternative approaches.

As I note here, in the Netherlands there’s an alternative via its “(semi)public sector” framework, which integrates public interest accountability with institutional autonomy. Dutch universities operate with clear governance standards that empower stakeholders, mandate transparency, enforce quality improvement, and cap senior staff pay – all while receiving substantial public investment. It recognises that universities are neither purely market actors nor government departments, but entities with distinct public service obligations.

When Belgian student services operate through distinct governance routes with direct student engagement, or when Norwegian student welfare is delivered through regional cooperative organisations, we see alternatives to both market competition and centralised planning.

They suggest that universities could maintain subject diversity and geographical access not through either unfettered market choice or central planning mandates, but through governance structures that systematically integrate the voices of students, staff, and regional stakeholders into portfolio decisions. The prisoner’s dilemma is solved not by altering individual incentives alone, but by fundamentally reimagining how decisions are made.

Other alternatives include better-targeted funding initiatives for strategically important subjects regardless of market demand, proper cross-institutional collaboration where universities collectively maintain subject breadth, regulatory frameworks that actually incentivise (rather than just warn against extremes in removing) geographical distribution of specialist provision, new metrics for university performance beyond enrolment and immediate graduate employment and better information for prospective students about long-term career pathways and societal value when multiple subject areas are on the degree transcript.

Another game to play

Game theory suggests that communication, coordination, and changing the incentive structure can transform the outcome.

First, we need policy interventions that incentivise the public good nature of higher education, rather than just demand minimums in it. Strategic funding for subjects – and crucially, minor pathways or modules – that are deemed nationally important, regardless of their current market demand, can maintain intellectual infrastructure. Incentives for regional subject provision might ensure geographical diversity.

Universities will need to stop using CMA as an excuse, and develop cooperative rather than competitive strategies. Regional consortia planning, subject-sharing agreements, and collaborative provision models are in the public interest, and will maintain breadth while allowing individual institutions to develop distinctive strengths.

Flexible pathways, shared core skills, interdisciplinary integration – all may prove more resilient against market pressures than narrowly defined single-subject degrees. They allow universities to maintain intellectual diversity while achieving operational efficiency. And they’re what Gen Z say they want. Some countries’ equivalents of QAA subject benchmarking statements have 10, or 15, with no less choice of pathways across and within them. In the UK we somehow maintain 59.

At the sector level, collaborative governance structures that overcome the coordination failure means resource-sharing for smaller subjects, and student mobility within and between regions even for those we might consider as “commuter students”.

OfS’ regulatory framework could be reformed to incentivise and reward collaboration rather than focusing primarily on institutional competition and financial sustainability. Funding could reintroduce targeted support for strategically important subjects, informed by decent mapping of subject (at module level) deserts and cold spots.

Most importantly, universities’ governing instruments should be reformed to explicitly recognise their status as “(semi)public sector bodies” with obligations beyond institutional self-interest – redefining success not as market share growth but as contributing to an accessible, diverse, and high-quality higher education system that serves both individual aspirations and collective needs.

Almost every scandal other than free speech – from VC pay to gifts inducements, from franchising fraud to campus closures, from grade inflation to international agents – is arguably one of the Simons’ deleterious side effects, which are collectively rapidly starting to look overwhelming. Even free speech is said by those who think there’s a problem to be caused by “pandering” to student consumers.

Universities survive because they serve purposes beyond market demands. They preserve and transmit knowledge across generations, challenge orthodoxies, generate unanticipated innovations, and prepare citizens for futures we can’t yet imagine.

If they respond solely to market signals, the is risk losing what makes them distinctive and valuable. That requires bravery – seeing beyond the apparent rationality of individual market optimisation to recognise the collective value of a diverse, accessible, and geographically distributed higher education sector.

It doesn’t mean running provision that students don’t want to study – but it does mean actively promoting valuable subjects to them if they matter, the government intervening to signal that quality can (and does) exist outside of the Russell Group, and it means structuring degrees such that some subjects and specialisms can be studied as components if not the title on the transcript.

It also very much requires civil servants and their ministers to wean themselves off the dominant orthodoxy of regulated markets as being the best or only way to do stuff.