The traditional flipped classroom model, which reverses the conventional lecture-homework structure, has evolved significantly since its inception. In the digital era, especially post-pandemic, this strategy has gained renewed importance for fostering active learning, critical thinking, and academic resilience. Today, the flipped classroom is no longer just about moving lectures online but about curating immersive, personalized learning environments. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), microlearning, and learning analytics provides new dimensions to this pedagogical approach, enhancing both student preparation and in-class engagement. This article explores how these three components can reshape flipped learning and address persistent challenges such as student unpreparedness, fear of participation, and lack of motivation.

Flipped Classroom 2.0: Enriching the Core Strategy

The original flipped classroom model aimed to reverse the traditional structure of education by shifting the transmission of basic content, often done through lectures, outside the classroom, while using face-to-face class time for active engagement and problem-solving. While this model offered significant benefits, the ever-changing dynamics of education in the digital era demand a more adaptive and responsive framework. This has led to the evolution of Flipped Classroom 2.0, a pedagogy that not only retains the foundational principles of the original model but enhances them with modern technologies and learner-centered practices.

AI Tools

In the Flipped Classroom 2.0 model, the learning process is amplified by integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools, which help personalize student learning pathways. AI-enabled systems such as adaptive learning platforms, chatbots, and generative tools like ChatGPT can provide students with on-demand explanations, simulate peer discussions, offer low-stakes quizzes, and give instant feedback. This technological support allows students to learn at their own pace and revisit complex material without feeling anxious or dependent solely on the instructor. From the educator’s side, AI tools help identify patterns in learner behavior and performance, allowing for more targeted interventions during class time.

Microlearning

Microlearning plays a central role in supporting pre-class preparation under the Flipped Classroom 2.0 framework. Instead of overwhelming students with lengthy video lectures or dense readings, microlearning delivers short, focused modules that concentrate on single learning objectives. These modules are ideal for students who are accustomed to fast-paced digital environments and may have limited attention spans. Microlearning enhances retention by segmenting information and reinforcing key concepts through repetition and brief assessments. It also empowers students to learn efficiently on mobile devices and during flexible hours, which is particularly valuable in hybrid and online learning contexts.

Learning Analytics

Learning analytics represents another foundational component of the Flipped Classroom 2.0 design. By utilizing Learning Management Systems (LMS) and built-in analytics dashboards, instructors can gain valuable insights into which students have completed pre-class activities, how they have performed, and where they may need additional support. Analytics tools also promote student accountability, as learners are able to track their own progress and receive early alerts when they are falling behind. These data-driven approaches make it possible to transition from reactive teaching to proactive guidance.

Collectively, these innovations: AI, microlearning, and learning analytics, enhance the effectiveness of the flipped classroom by aligning content delivery, student support, and real-time feedback. Flipped Classroom 2.0 is not merely a technological upgrade; it is a reimagined learning experience that promotes self-directed learning, critical thinking, and inclusivity. It encourages students to become active participants rather than passive recipients, and it positions educators as facilitators and data-informed decision-makers in the learning process.

Understanding Student Resistance in the Digital Era

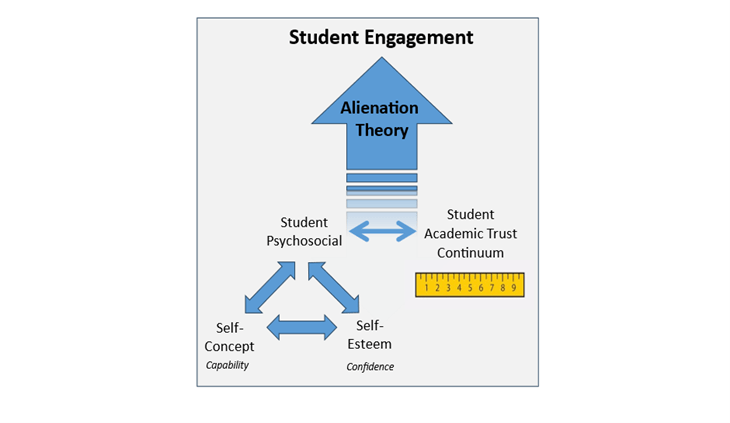

Unpreparedness often stems not from laziness or disinterest, but from deeper psychological or contextual barriers that influence a student’s ability to engage. In many cases, students may feel overwhelmed by the unfamiliarity of new instructional models or lack the confidence needed to navigate them successfully. This resistance is especially prominent in environments where flipped classroom strategies are introduced abruptly or without adequate scaffolding. In digitally enhanced learning spaces, Artificial Intelligence tools can serve as diagnostic aids to help educators understand the roots of student resistance.

By monitoring metrics such as time spent on tasks, levels of participation, and types of interactions within pre-class activities, AI systems can identify patterns of disengagement or confusion. For example, if students frequently abandon certain video modules or quiz sections, this may signal content complexity, misalignment with learning styles, or underlying cognitive fatigue. Moreover, many students, especially those transitioning from traditional learning environments, may carry negative assumptions about active learning approaches. They may perceive them as chaotic, unpredictable, or more demanding than passive learning formats. Educators must dig deeper to explore these sentiments and confront the emotional undercurrents that influence classroom behavior. Addressing resistance with empathy, transparency, and gradual acclimatization is crucial for long-term student buy-in.

Addressing Fear Through Technology-Supported Safety

Fear is one of the most formidable barriers to classroom participation. Whether it’s the fear of giving incorrect answers, speaking publicly, or being judged by peers, these emotions can significantly hinder student engagement. In the flipped classroom, where much of the responsibility for learning shifts to students, this fear may become even more pronounced if not properly addressed. Technology, particularly AI-driven tools, can be strategically used to create psychologically safe learning environments. For example, private practice environments powered by chatbots or simulations can offer students a space to make mistakes, ask questions, and rehearse ideas without fear of embarrassment. These tools are particularly beneficial for introverted students or those who lack confidence in their subject knowledge.

Microlearning also plays a vital role in reducing anxiety. By breaking down complex content into manageable chunks, students can focus on mastering one concept at a time. This incremental mastery builds confidence and reduces cognitive overload. When paired with formative assessments and feedback loops, microlearning helps normalize error-making as part of the learning process. Analytics further enhance psychological safety by providing both educators and students with objective data on progress. When students see that others are also struggling with the same concepts or that their performance is gradually improving, they are more likely to perceive learning as a collective and iterative journey.

Making Learning Visible with Analytics and Scaffolds

Visibility of learning progress is essential in maintaining student accountability and fostering meaningful classroom interactions. In traditional flipped classrooms, instructors often face the challenge of determining whether students have genuinely completed pre-class tasks or engaged with the material in a substantive way.

Flipped Classroom 2.0 addresses this issue by leveraging data and scaffolding techniques that make learning both measurable and visible. Learning analytics tools embedded in LMS platforms can track completion rates, quiz scores, engagement time, and areas of difficulty. This data is accessible to both teachers and students through visual dashboards, which serve as powerful motivators and intervention tools. Educators can use this information to adjust instruction, form differentiated groups and provide individualized support. Scaffolding further supports this visibility. Templates, guided note-taking structures, interactive mind maps, and learning journals help students organize their thoughts and reflect on their understanding. When integrated with AI, these scaffolds can be customized based on student performance and learning preferences. This transparency not only improves learning outcomes but also enhances communication between instructors and students.

Designing Pre-Class Work That Drives In-Class Success

A key feature of the flipped classroom model is the dependency on students completing pre-class work so they can actively participate in class discussions and activities. However, the perceived value of pre-class tasks directly influences student compliance and effort. To elevate this value, educators must clearly connect pre-class preparation with in-class success. AI can support this connection by generating customized content summaries, quizzes, and diagnostic questions based on each student’s pre-class performance. For instance, if a student demonstrates mastery of foundational concepts, they can be prompted with higher-order questions to challenge their thinking. Conversely, students who struggle can be provided with remedial resources and practice modules. In-class activities should build directly on pre-class efforts. Group discussions, simulations, debates, and problem-solving exercises should reference or utilize outputs from the pre-class assignments. This integration reinforces the message that preparation is essential for success and ensures that students recognize the practical benefits of investing time in asynchronous learning.

Gamification techniques, such as digital badges, progress milestones, and peer recognition can further motivate students to complete pre-class tasks. When these activities contribute to course grades or unlock exclusive learning opportunities, their relevance is amplified.

Establishing Routine and Engagement with Focusing Activities

The transition from asynchronous pre-class learning to synchronous in-class application can be challenging if not facilitated through structured routines. Focusing activities, particularly those conducted at the beginning of class, serve as critical bridges that help students activate prior knowledge and reorient their attention. These activities may include short reflective prompts, polls, problem-solving warmups, or collaborative brainstorming sessions. When enhanced with technology, focusing activities become even more impactful. For example, AI-driven polling platforms can pose adaptive questions tailored to the students’ recent performance.

Visualization tools can help students construct or revise concept maps based on their understanding of the pre-class content. Establishing predictable routines around these activities builds habits of participation. Over time, students internalize the rhythm of flipped learning: prepare independently, apply collaboratively, reflect continuously. Such engagement patterns increase cognitive readiness and reduce classroom management challenges.

Avoiding Pitfalls in Tech-Enhanced Flipped Classrooms

While Flipped Classroom 2.0 offers numerous benefits, its success is contingent upon thoughtful implementation. Several common pitfalls can undermine the model’s effectiveness. One of the most prevalent mistakes is treating technology as a substitute for pedagogy. Simply replacing lectures with videos or adding quizzes does not constitute a true flip. Without alignment to learning objectives and instructional goals, these tools can confuse rather than support learners.

Another challenge is content overload. Students may feel overwhelmed if asked to review long readings, videos, and quizzes without clear guidance or purpose. Microlearning and scaffolding should be used to break down materials and provide learning pathways that are manageable and coherent. Educator readiness is another often-overlooked factor. Successful adoption of AI tools and data dashboards requires faculty training and support. Instructors must be equipped not only with technical skills but also with an understanding of how to interpret analytics and adjust pedagogy accordingly.

Lastly, student feedback should be incorporated into the design and refinement of flipped classroom practices. Continuous evaluation, surveys, and informal check-ins can reveal usability issues and highlight opportunities for improvement.

Toward a Future-Ready Learning Model

Reimagining the flipped classroom requires more than adopting trendy tools, it demands a philosophical shift. By combining AI, microlearning, and learning analytics, educators can create classrooms that are not only flipped but also fluid, feedback-driven, and future-ready. These strategies support student autonomy, foster critical thinking, and build academic resilience in an unpredictable world. The next frontier of flipped learning is not about technology for its own sake, but about purposeful integration that places learners at the center.

N. P. K. Ekanayake

Ms. Neranjana Priyangani Kumari Ekanayake, a senior lecturer at the University of Kelaniya, teaches Investment and Portfolio Management, Enterprise Resource Planning, Behavioural Finance, and Advanced Management Accounting. She holds a BBA in Accounting (Special) and an MSc in MMs. Neranjana Priyangani Kumari Ekanayake, a senior lecturer at the University of Kelaniya, teaches Investment and Portfolio Management, Enterprise Resource Planning, Behavioural Finance, and Advanced Management Accounting. She holds a BBA in Accounting (Special) first-class and an MSc in Management (Specialized in Finance) and is a CIMA passed finalist. Further she has completed a Diploma in Enterprise Resource Planning in University of Kelaniya.

N.K.L. Silva

Ms. Nilanthige Kaushalya Lakmali Silva is a Lecturer at the Department of Accountancy, University of Kelaniya. She teaches Management, Economics, Human Resource Management, Marketing Management, Strategic Management and Information Management. Ms. Silva holds a B.B.Mgt. (Special) Degree in Accountancy with a First-Class Honours and an M.Sc. in Management with a Merit. Her research interests include major areas of Accounting and Finance, with a particular focus on Sri Lanka’s Capital Markets, Micro and Macro Economic Environment, Corporate Governance, and Corporate Fraud. She has published several research papers in academic journals and conference proceedings. She is a CMA Sri Lanka Passed Finalist and has completed the Diploma in Banking and Finance at the Institute of Bankers of Sri Lanka.

References

Berrett, D. (2012, February 19). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-flipping-the-classroom-can-improve-the-traditional-lecture/130857

Gerstein, J. (2012, May 15). Flipped classroom: The full picture for higher education. User Generated Education. https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2012/05/15/flipped-classroom-the-full-picture-for-higher-education/