It can feel like the rhetoric around AI is shifting as fast as its ability to generate content. In the English language education sector, we only need look to the recent past to recall how searching questions like “will we need humans in the future?” and “is it game over for teachers?” were the focus of every conference agenda, leadership summit and coffee room discussion.

These types of questions resonate in all sectors of industry, and it was no surprise to see a recent episode of Dispatches on Channel 4 ask: “will AI take my job?”

More focus on practical and ethical considerations

But recently, something’s changed. We are becoming more comfortable with the idea that we can meaningfully coexist with this technology. And, with this change, industry leaders and policymakers in English language education are becoming more focussed on the practical and ethical questions around delivering AI in education, such as: how and when AI should be used and, in in some cases, should it even be used at all?

This marks a welcome shift in perspective, one where people accept that this technology is here to stay but are genuinely engaging with how we can take sensible steps to get the best out of it. It’s critical to remember that ethical considerations for AI shouldn’t just be a simple box ticking exercise, as pointed out by UNESCO UK in their 2025 anthology – which says ethical AI in education is about building fair, human-centred systems that truly support meaningful learning.

‘Why’ is the biggest question of all!

When it comes to AI in education, ‘why’ is perhaps the biggest question we need to ask ourselves. The short answer to this is: ‘if it adds value.’ We also need to ask: ‘does it make sense’. Ethical concerns come in many shapes and sizes, but one we cannot ignore is the sustainability challenges surrounding this energy hungry technology.

Whether you’re using AI to teach or assess English, at the heart of this must be a human in control

So, before embarking on any AI related project in our sector, it’s critical to ask whether we in fact need it, or if there are more sustainable options available. In other words: do we need to build a new large language model (LLM), or does an existing method, or simpler alternative, work just as well and have a far smaller carbon footprint?

How should we use AI?

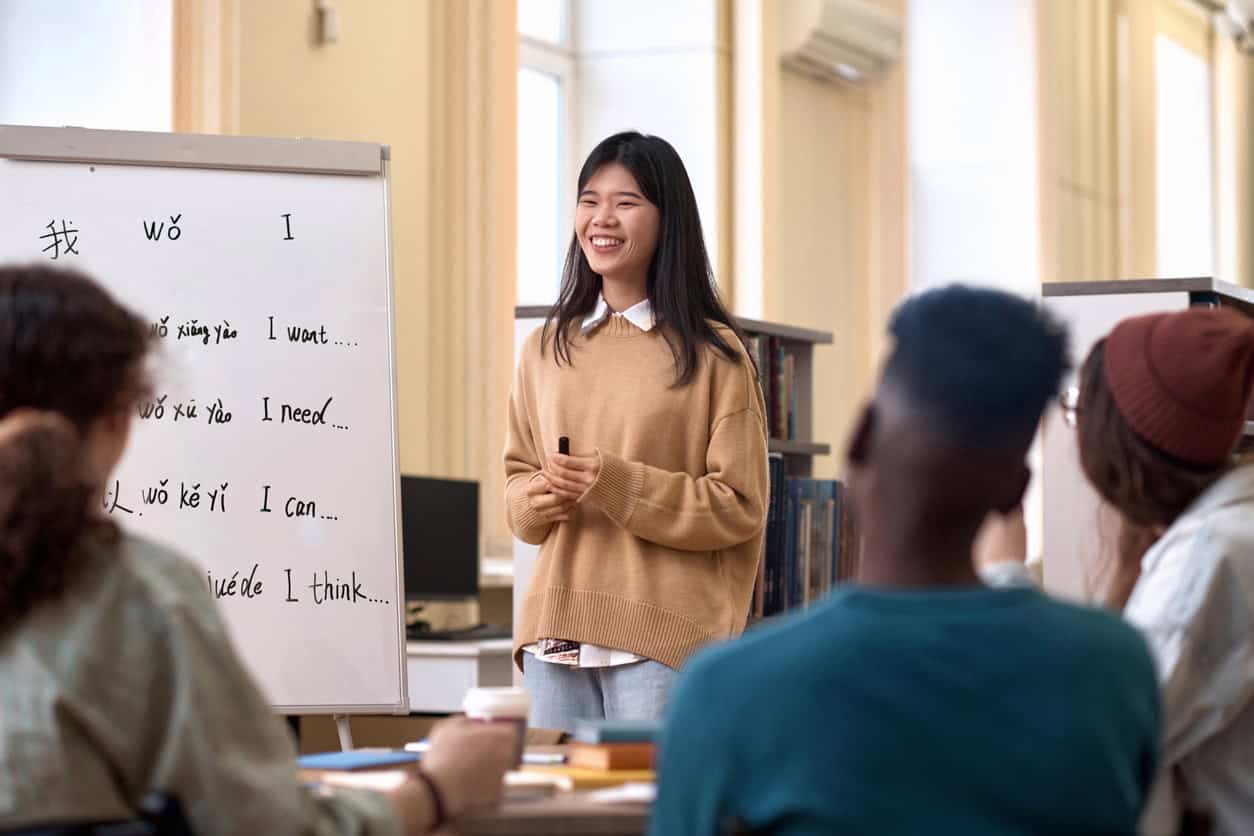

In terms of how we should use AI, again there are lots of practical and ethical considerations. Whether you’re using AI to teach or assess English, at the heart of this must be a human in control. The need for maintaining a ‘human in the loop’ is for several reasons, but mainly because learning a language is a very human-centred process and, while AI can bring enormous benefits, it cannot replicate the uniquely human experience of acquiring and using language. And, of course, there are practical reasons too – especially when it comes to quality control in assessment, where we need humans to sometimes step in and offer oversight and clarity.

What about high stakes assessment?

This need for a ‘human in the loop’ is particularly pertinent in high-stakes assessment. It’s essential that in these cases, we do not prioritise convenience over quality, and we continue to develop robust solutions. If we use the technology to cut corners, this ultimately does a disservice to students and runs the risk of them not developing the English skills they need for success.

The ingredients for trustworthy AI

If we are serious about delivering ethical AI, another area to consider is fairness and ensuring that systems are free from bias. To achieve this, it’s critical that AI-based language learning and assessment systems are trained on diverse and inclusive data and are constantly monitored for bias. And of course, we have to consider data privacy and consent which in practice means all parties must be clearly informed about what data is collected, how it’s stored, and how it is going to be used.

A week is a long time in AI!

The extraordinary pace of change when it comes to AI reminds me of the famous quote about how a week is a long time in politics. One thing is certain: we’re at a significant moment for language education. As we continue to shift towards a future where human-led AI can deliver high quality education, it is more critical than ever to ensure that ethical use matters. Fairness, transparency, and sustainability must remain non‑negotiable. Without this, AI will fast lose credibility in English language learning and assessment – to the detriment of both innovation and our students.

Ultimately, our collective goal as education leaders is simple: to deliver meaningful AI that meets robust ethical standards and adds true value for learners.

To find out more, read our paper Ethical AI for Language Learning and Assessment, by my colleagues Dr Carla Pastorino-Campos and Dr Nick Saville.

About the author: Francesca Woodward is global managing director for English at Cambridge University Press & Assessment.