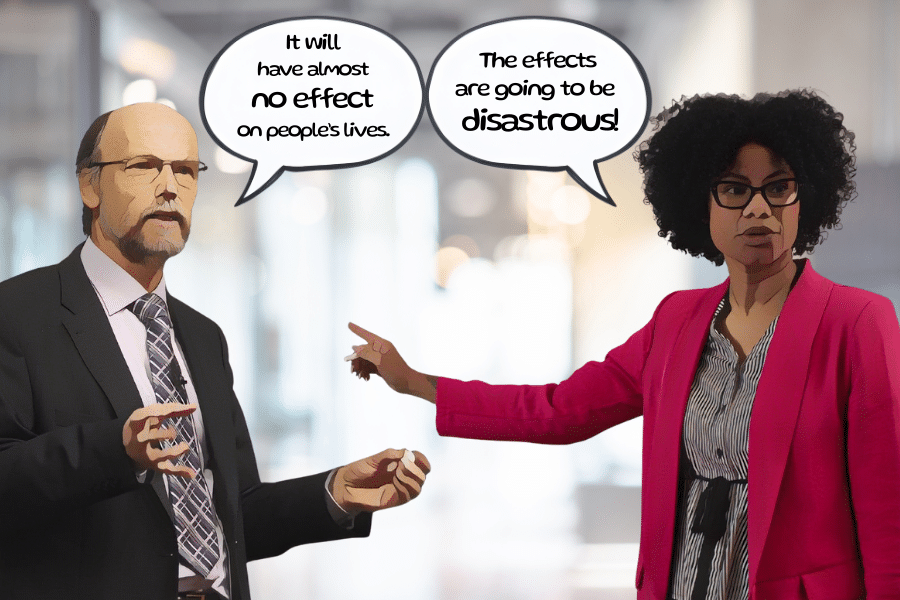

Journalists are often told to be objective and to tell both sides of a story. They are taught to seek multiple perspectives. This means that when reporters interview an expert about any given topic, they are encouraged to find another source with a different opinion to make it “fair” and “balanced”.

Journalists also know that conflict makes a story more interesting and that gets more eyeballs or ears which allows their news organizations to sell more ads and subscriptions.

But research any topic and you will find disagreements among scientists, ecologists, business leaders, politicians and everyday people. In other words you can just about always find conflict.

Be careful of this. In homing in on conflict you could create a false balance. That’s when you make two sides seem more equal than they are.

The classic example is climate change. One of the reasons why it took so long for governments to recognize the danger of climate change is that for years journalists would balance the many, many scientists warning about carbon levels with the very few scientists who said the problem was overblown.

So how can you report multiple perspectives without creating a false sense of balance?

A few suggestions

Focus on facts, not opinions. And know the difference.

A fact can be verified through data and anecdotes of things that happened and that can also be verified.

When sources give you information, ask them: “How do you know that?” and “Do you have evidence to back that up?”

Even when they have evidence to back up what they say, question why they take the stand they take, or why they came to the conclusions that they did. It is almost as easy to find evidence to support a position as it is to find conflict in a story. I found myself almost believing that the earth is indeed flat when an advocate of that theory seemed to offer up a pile of convincing evidence.

To get the public to not worry about the dangers of tobacco, people from the tobacco industry offered up all kinds of evidence for years. People from the fossil fuels industry can offer up all kinds of evidence that human behavior (like driving petrol-powered cars) doesn’t cause climate change.

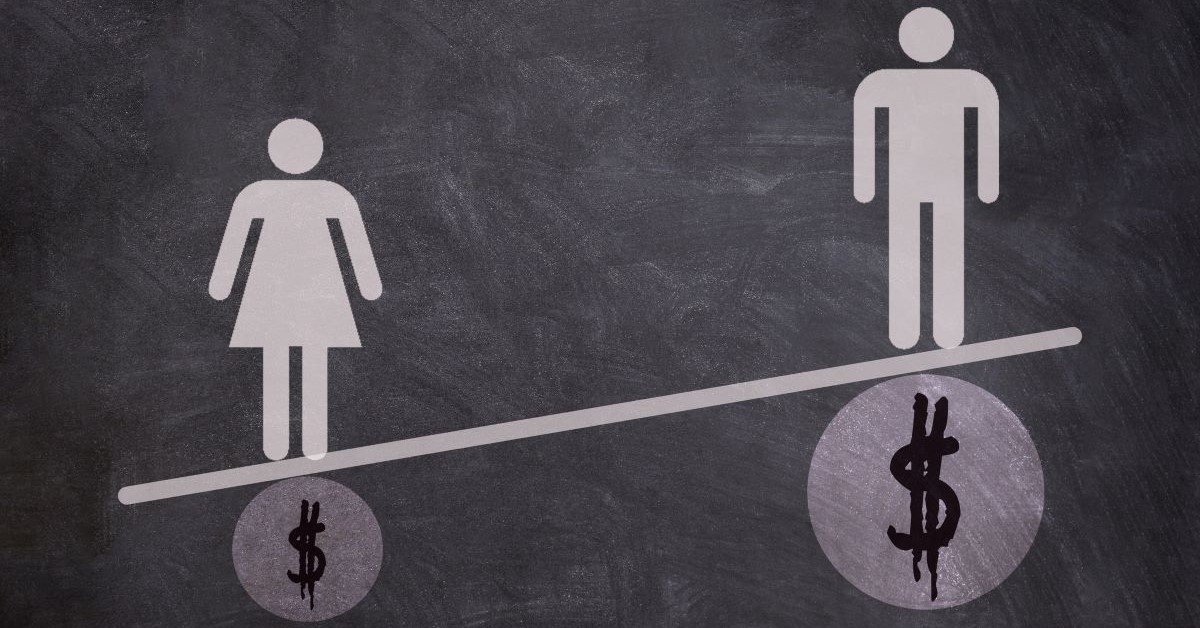

So it is important when you publish information someone has given you, to explain to your audience how that person benefits or is hurt by the issue.

Not all experts are equal.

When seeking opinions or assessments, do so from people with actual expertise. That’s not the same as a level of education or a fancy title. Don’t be afraid to ask people: “How do you know this?” Someone without a university degree might have lived experience with a problem, while someone with a doctorate might never have experienced what you are reporting on. Politicians are fond of talking about the problems of poor people even though many of them came from privileged backgrounds.

Don’t be afraid to challenge people’s statements. Let them know when you find contradictory information. When you challenge people it is not a sign of disrespect. It is a sign that you have carefully listened to what they said, have thought about it and are now questioning it. Disrespect is to take something someone says without really listening or thinking about it.

Question data people cite or that you find. A census conducted in 2010 in Nabon, a rural area in Ecuador, found that almost 90% of the population was “poor”. That’s an astounding figure, and if used as data in the media, paints a very particular picture. However, a different study in 2013, conducted by the University of Quenca with the Nabon municipal government at the time, found a significantly different figure — that about 75% of the population reported to be highly satisfied with their lives when assessing “subjective wellbeing”.

The difference in figures is due to the indicators used to measure satisfaction. The “subjective wellbeing” survey by the University of Quenca measured people’s control over their lives, satisfaction with their occupation, financial situation, their environmental surroundings, family life, leisure time, spiritual life and food security. The census from 2010, however, looked at housing, access to health and education and monetary income.

So the language used for measuring life satisfaction was important and that the context of the data — how and why it was collected — can change the meaning of the information. To make sure you don’t misreport data, try to avoid overly relying on just one source of numbers or statistics. Instead, check what other data is out there.

Report the reality.

Your job as a journalist is to present the information in such a way that your audience can recognise what is actually happening and why it’s important.

Does what the experts say or what people say about their personal experience go against what you have seen out there yourself? People often exaggerate without even realizing that they are doing so. Our memories are often faulty; we might think we know things that we really don’t.

Taking all this into account, it is ultimately up to you, as a journalist, to decide how much balance to give to the multiple perspectives you have gathered. If the experiences and evidence and your observations and common sense all point to a reality, then you will mislead your audience if you balance that out equally with people who offer up what seems to be a different reality.

That doesn’t mean that you should silence them or keep them out of the story altogether. Understanding and exploring opposing viewpoints is important so that ultimately people can reach an understanding.

Without that understanding, consensus isn’t possible. And it is difficult to make progress in a society without consensus.