A recent op-ed by David Randall, executive director of the Civics Alliance and director of research at the National Association of Scholars, argues that faculty hiring in American universities has become so corrupt that it requires sweeping legislative intervention. NAS’s proposed Faculty Merit Act would require public universities to publish every higher ed standardized test score—SAT, ACT, GRE, LSAT, MCAT and more—of every faculty member and every applicant for that faculty member’s position across different stages of a faculty search. The goal, they claim, is to expose discrimination and restore meritocracy.

The proposal’s logic is explicit: If standardized test scores are a reasonable proxy for faculty merit, then a fair search should select someone with a very high score. If average scores decline from round to round, or if the eventual hire scored lower than dozens—or even hundreds—of rejected applicants, the public, Randall argues, should be able to “see that something is wrong.”

But the Faculty Merit Act rests on a serious misunderstanding of how measurement and selection actually work. Even if one accepts Randall’s premise that a standardized test score “isn’t a bad proxy for faculty merit,” the conclusions he draws simply do not follow. The supposed red flags the proposed act promises to reveal are not evidence of corruption. They are the expected mathematical consequences of using an imperfect measure in a large applicant pool.

I am a data scientist who works on issues of social justice. What concerns me is not only that NAS’s proposal is statistically unsound, but that it would mislead the public while presenting itself as transparent.

A Statistical Mistake

The proposed act depends on a simple idea: If standardized test scores are a reasonable proxy for faculty merit, then a fair search should select someone with a very high score. If the person hired has a lower score than many rejected applicants, or if average scores decline from round to round, something must be amiss.

This sounds intuitive. It is also wrong.

To see why, imagine the following setup. Every applicant has some level of “true merit” for a faculty job—originality, research judgment, teaching ability, intellectual fit. We cannot observe this truth directly. Instead, we observe a standardized test score, which captures some aspects of ability but misses many others. In other words, the test score contains two parts: a signal (the part related to actual merit) and noise (everything else the test does not measure).

Now suppose a search attracts 300 applicants, as in Randall’s own example. Assume—very generously—that the search committee somehow identifies the single best applicant by true merit and hires that person.

Here is the crucial point: Even if test scores are meaningfully related to true merit, the best applicant will almost never have the highest test score.

Why? Because when many people are competing, even moderate noise overwhelms rank ordering. A noisy measure will always misrank some individuals, and the larger the pool, the more dramatic those misrankings become. This is the same reason that ranking professional athletes by a single skill—free-throw percentage, say—would routinely misidentify the best overall players, especially in a large league.

How Strong Is the Test-Merit Relationship, Really?

Before putting numbers on this, we should ask a basic empirical question: How strongly do standardized tests actually predict the kinds of outcomes that matter in academia?

The most comprehensive recent research on the GRE—the test most relevant to graduate education—finds minimal predictive value. A meta-analysis of more than 200 studies found that GRE scores explain just over 3 percent of the variation in graduate outcomes such as GPA, degree completion and licensing exam performance. For graduate GPA specifically—the outcome the test is explicitly designed to predict—GRE scores explained only about 4 percent of the variance.

These studies assess near-term prediction within the same educational context: GRE scores predicting outcomes for the very students who took the test, measured only a few years later—under conditions maximally favorable to the test’s validity. The NAS proposal extrapolates from evidence that is already weak even under these favorable conditions. It would evaluate faculty hiring using test scores—often SAT scores—taken at age 17, applied to candidates who may now be in their 30s, 40s or older. Direct evidence for that kind of long-term extrapolation is scarce. However, the limited evidence that does exist points towards weak relationships rather than strong ones. For instance, Google’s internal hiring studies famously found “very little correlation” between SAT scores and job performance.

Taken together, the research suggests that any realistic relationship between standardized test scores and faculty merit is weak—certainly well below the levels needed to support NAS’s proposed diagnostics.

What This Means in Practice

The proposed Faculty Merit Act raises an important practical question: Even if standardized test scores contain some information about merit, how useful are they when hundreds of applicants compete for a single job?

Taking the GRE meta-analysis at face value, standardized test scores correlate with relevant academic outcomes at only about 0.18. Treating that number as a proxy for faculty merit is already generous, given the decades that often separate testing from hiring and the profound differences between standardized exams and the actual work of a professor. But let us grant it anyway.

Now, consider a search with 300 applicants. With a correlation of 0.18, I calculate that the single strongest candidate by true merit would typically score only around the 70th percentile on the test—roughly 90th out of 300. In other words, it would be entirely normal for around 90 rejected applicants to have higher test scores than the eventual hire.

Nothing improper has happened. No favoritism or manipulation is required. This outcome follows automatically from combining a weak proxy with a large applicant pool.

Even if we assume a much stronger relationship—say, a correlation of 0.30, which already exceeds what the evidence supports for most academic outcomes—the basic conclusion does not change. Under that assumption, I calculate that the best candidate would typically score only around the 80th percentile, corresponding to a rank near 60 out of 300. Dozens of rejected applicants would still have higher test scores than the person who gets the job.

This is the point the proposal gets exactly backward. The pattern it treats as a red flag—a hire whose test score is lower than that of many rejected applicants—is not evidence of corruption. It is the normal, mathematically expected outcome whenever selection relies on an imperfect measure. Scaling this diagnostic across many searches does not make it informative; it simply reproduces the same expected misrankings at a larger scale.

Why ‘Scores Dropped Each Round’ Proves Nothing

The same logic applies to the claim that average test scores should increase at each stage of a search.

Faculty hiring is not one-dimensional. Early stages might screen for general competence; later stages may emphasize originality, research direction, teaching effectiveness and departmental fit—traits that standardized tests measure poorly or not at all. As a search progresses, committees naturally place less weight on test scores and more weight on other information. When that happens, average test scores among finalists can stay flat or even decline. That pattern does not signal manipulation. It signals that the committee is selecting on dimensions that actually matter for the job.

Transparency, Justice and Bad Diagnostics

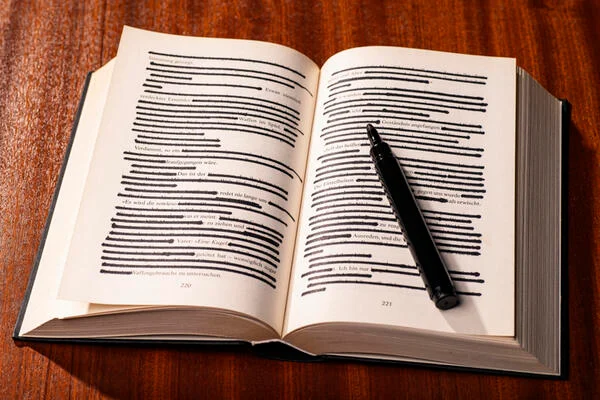

Randall’s op-ed, published by the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, frames the proposal as a response to injustice. But transparency based on invalid diagnostics does not mitigate injustice; it produces it.

Publishing standardized test scores invites the public to draw conclusions that those numbers cannot support—and those conclusions will not fall evenly. Standardized test scores are strongly shaped by socioeconomic background and access to resources. Treating them as a universal yardstick of merit—especially for faculty careers—will predictably disadvantage scholars from marginalized and nontraditional paths.

From the standpoint of justice, this is deeply concerning. Accountability mechanisms must rest on sound reasoning. Otherwise, they become tools for enforcing hierarchy rather than fairness.

If the goal is genuine academic renewal, it should begin with renewing our understanding of what numbers can—and cannot—tell us. Merit cannot be mandated by publishing the wrong metrics, and justice is not served by statistical arguments that collapse under careful inspection.