The potential policy changes could give international students another hoop to jump through, further burdening consulates and embassies.

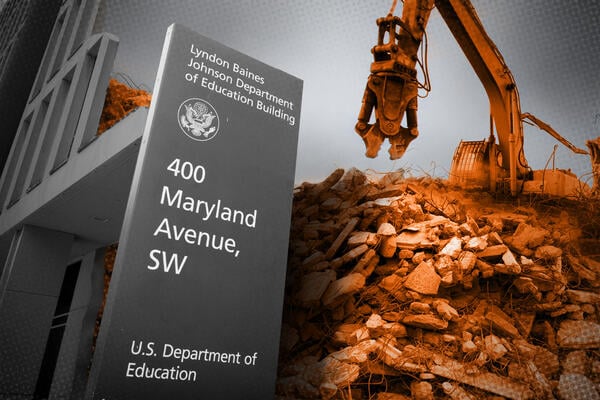

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | tarras79/iStock/Getty Images

The Trump administration is planning to limit how long international students can remain in the U.S., likely mirroring a plan proposed at the end of Trump’s first term with the same name, advocacy groups and immigration attorneys say.

The regulations are expected to replace “duration of status,” a 1991 rule that allows international students to remain in the country as long as they are enrolled at a college or university. In 2020, the administration proposed limiting that time to just four years—a period shorter than most Ph.D. programs and shorter than the average student takes to complete a bachelor’s degree—though it would have allowed students to apply for extensions. Students from certain countries, including those the administration said were state sponsors of terrorism and those with high overstay rates, would have been afforded just two years.

That rule was withdrawn after President Joe Biden entered office. But the Trump administration is poised to propose it once again, based on a submission to the Office of Management and Budget. The Department of Homeland Security has yet to release details about the potential change, but a pending rule change with the same name as the 2020 proposal was sent to OMB in late June and approved Aug. 7. However, according to OMB’s website, the rule is now under review once again for unknown reasons. Neither OMB nor DHS responded to Inside Higher Ed’s request for comment. Until OMB signs off, DHS can’t publicly release the plan and take public comments.

The anticipated proposal comes amid the Trump administration’s ongoing attacks on international students, which included the sudden and unexplained terminations of students’ records in the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System, the database that tracks international students, in March and April. The administration has also taken steps to make it more difficult for prospective students to receive F-1 visas, including reviewing all applicants’ social media profiles.

Incoming international students, meanwhile, are struggling with long delays for visa interviews as a result of federal layoffs and a pause in student visa appointments this spring, leading to concerns that international enrollment could drop this fall semester. Changing duration of status, advocates say, would only gum up the works even more, giving international students another hoop to jump through and further burdening consulates and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

“This is not just one particular proposed rule or change in policy; it fits within a number of policy changes that we’ve experienced throughout the past eight months that the administration has been in control,” said Jill Allen Murray, deputy executive director for public policy at NAFSA, the association for international education professionals. “Many of those interact with each other and make it much more difficult for international students to take the steps that are necessary to come to the United States and study, and this would be yet another challenge for students.”

A ‘Regulated Population’

Why is the administration looking to eliminate duration of stay? If its reasoning is the same as in 2020, it is aiming to reduce fraud and visa overstays.

International students are indeed one of very few nonimmigrant categories allowed to stay in the U.S. indefinitely, giving them special flexibility so they can finish their studies. But Samira Pardanani, associate vice president of international education and global engagement at Shoreline College, argued that doesn’t mean there’s any reason to believe duration of status leads students to be more likely to overstay.

“This is a very, very regulated population … there’s a lot of follow-up schools do with regards to helping students maintain their status, and there are a lot of record-keeping and reporting requirements for schools,” Pardanani said. “Duration of status is something that has been, in my opinion, working well.”

Murray also noted that the F-1 visa overstay rate reported by the government is not necessarily reliable, by DHS’s own admission.

Another policy aimed at streamlining the visa process for nonimmigrant visitors, including international students, is also on the chopping block. On Sept. 2, the Trump administration will end interview waivers for many nonimmigrant groups, including international students. Those waivers, which started during the COVID-19 pandemic, allow certain individuals whose visas have expired but who have maintained their lawful nonimmigrant status to renew their visas without an in-person consular interview.

The duration of a visa depends on the country and can range from a few months to several years. Thanks to interview waivers, an international Ph.D. student whose visa had expired could visit home in the summer, easily renew their visa without an in-person appointment and return the next semester without issue. But now, they would have to return to the consulate in their country even for a routine visa renewal.

Pardanani said she did not think the elimination of interview waivers was inherently problematic, but “right now, when there’s already a lot of visa backlogs and students are not getting visa appointments … it’s going to have a deeper impact in students and on universities and colleges.”